“It is the true Arabia … there can never be another picture of the whole, in our time, because here it is all said, and by a great master” T. E. Lawrence

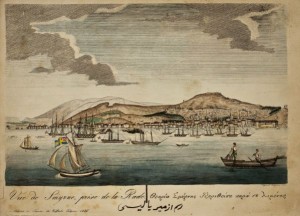

Setting off from Damascus in 1876, Charles Doughty travelled for 21 months across the deserts of Arabia, through regions almost entirely unknown to Western eyes. He faced many hazards, from malnutrition and heat exhaustion to attack by hostile Wahhabi communities. Initially he travelled with the Hajj, before venturing into the desert interior alongside a Bedouin family and other nomadic groups. He reached the city of Unayzah, in central Arabia, and finally arrived at the Red Sea port of Jeddah in 1878.

His account of this remarkable journey is considered to be one of the finest travel books in the English language and inspired T. E. Lawrence’s excursions thirty years later. Despite its abundant merits, it was little known until Lawrence became its most avid and practical reader, using it as a guide during his travels across Arabia and admiring its descriptions of a bygone way of life. Lawrence provided a preface to the 3rd edition, published in 1921.

The Folio Society has recently published a new edition of Travels in Arabia Deserta. The new edition includes a preface by the author and politician Rory Stewart, in addition to Lawrence’s tribute. Stewart underlines the importance of Doughty’s achievement, saying that “no one who is seriously interested in travel or Arab custom, or indeed the extremity of human experience, can afford to ignore this book”.

While the original edition was illustrated with line drawings, the new version also includes 48 photographs from the period, selected from the collections of the Fine Arts Library. These images, from our extensive holdings of photographs by the Maison Bonfils, provide a new visual context for Doughty’s travels. Creating digital files for the publication gave us the opportunity to include a few more of these evocative images in VIA, Harvard’s online image catalog.