This post is the fourth in a series about the Stuart Cary Welch Islamic and South Asian Photograph Collection written by the project’s staff and student catalogers in the Digital Images and Slides Collections of the Fine Arts Library.

Written by Nicolas Roth

The Stuart Cary Welch Islamic and South Asian Photograph Collection is a great resource for research, and not just for art historians. A PhD candidate in the Department of South Asian Studies, I have had the privilege of working with the images in the collection as a student cataloger since the beginning of this year. Exploring Stuart Cary Welch’s often masterfully beautiful images of artwork and architecture from South Asia and the wider Islamic World is a joy in its own right. There are photographs of works not published elsewhere, and while these often present a frustrating challenge for us as catalogers, they are nonetheless a bit like buried treasure when one comes upon them. Yet even of comparatively well-known pieces the collection sometimes has better – clearer, brighter, higher-resolution – images than those available in printed publications or elsewhere online. Moreover, Welch frequently took detail shots of interesting features of a work; these are particularly valuable in the case of Indian and Iranian manuscript illuminations and album paintings, with their often small size but prodigious detail. However, the time spent with the collection has also turned out to be quite fruitful for my own research, and has resulted in ample visual material to weave into my dissertation.

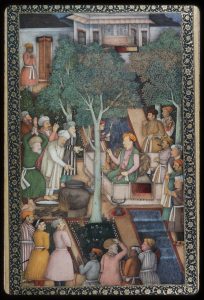

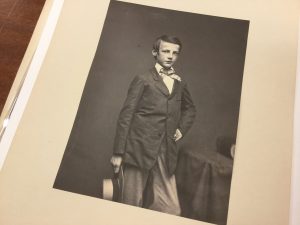

My project focuses on horticultural writing and garden culture in Mughal India – that is, the role of gardens and gardening in the intellectual and social life of early modern South Asia, and its reflection across a wide variety of literary genres. Images of gardens, horticultural practices, and plants in Mughal and Rajput paintings are an important complement to these texts, or even a set of texts in themselves. Take, for instance, the above painting of Mughal Emperor Jahangir in a garden by the court artist Abu’l Hasan, painted between 1615 and 1620. Not only does it reflect garden layout – a central watercourse, a pavilion set into the garden’s enclosing wall, rectangular, slightly sunken flowerbeds – but also an identifiable plant palette of Oriental plane trees and narcissi and irises in the flowerbeds. While all three of these plants frequently appear in Mughal painting as motifs inherited from Persian literature and Timurid pictorial tradition, their combined and realistic appearance here, in conjunction with the absence of any of the tropical plants frequently depicted in Mughal art, suggests that this is meant to be a garden in the temperate parts of the Mughal Empire in Kashmir or Afghanistan. The crowd of scholars and noblemen around Jahangir and the cauldron set up to prepare food point to the social use of gardens as a setting for various types of receptions, while the minutely detailed candles and torches indicate that this particular event is taking place at night.

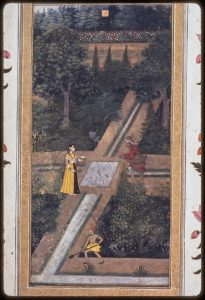

A similar level of detail can be discerned in this next scene above painted around the same time and now included in an album held at the Bodleian Library in Oxford. Here, however, the garden is only populated by three human figures: two gardeners, one with a spade and one with an animal skin filled with water, and a woman who has evidently been collecting flowers from the garden, as she is holding a bouquet in one hand and a leaf bowl of white blossoms in the other. The sunken beds in this garden are densely planted with trees, flowering shrubs, and some herbaceous flowers. In the background, a border of poppies is blooming brightly against a dense wall of trees. About a century later, an artist at the court of the Emperor Muhammad Shah produced a rendering of a garden that appears to synthesize all the features discussed in the elaborate garden set pieces of contemporary Indian literary works, such as these in a passage from a lengthy garden description in the Masnavī-i dilpazīr of Sa‘ādat Yār Khān ‘Rangīn’ (1757-1835), written in 1798:

Across from the central gate was a canal / Whose waves were no less than those of the Narmada River

All the way from the portico to there / Fountains were spouting forth from it

…

Cascades were falling from them / As if the rains of Sāvan and Bhādon were falling day and night

In front of them such showers came down / A cloud would be daunted coming before them

The trelliswork on both sides of the walkway / How can anyone describe it!

Having ordered sandalwood and ebony / And having had them split by craftsmen

Wooden pergolas were made / Like those in the squares of Kabul

Grapevines were made to grow all over them / So that no one be bothered by the sun

On both sides water was flowing / In this manner was this walk laid out

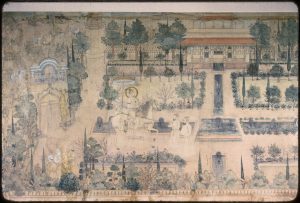

In the garden Muhammad Shah visits in the painting, watercourses adorned by impressive fountains run from the stately entrance gateway and an ornate, multi-storied pavilion set into the back wall of the garden to intersect at a square pool in its center. Borders of roses, poppies, marigolds, and other flowers line the paths along the watercourses, and wooden pergolas run along the walls of the garden on either side of the pavilion.

In Stuart Cary Welch’s detail shots, the grape vines trained over the trellises can be discerned particularly well, as can the exquisite detail of the flowering banana plants and campā trees in the row of trees at the very front of the painting. The latter is a type of magnolia, Magnolia champaca, with extremely fragrant yellow flowers which was much celebrated in Indian literary traditions, including in the Persian poetry produced in India by both Indian-born and Iranian émigré poets.

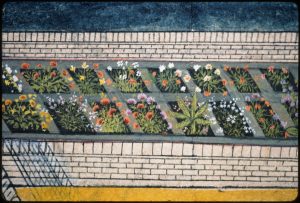

Fort Walls and Garden

Fort Walls and Garden_detail

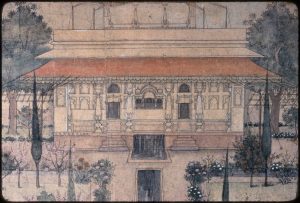

The last work I chose to highlight, produced by Shaykh Taju at the Rajput court of Kota in Rajasthan in the mid-eighteenth century, is somewhat different from these Mughal works, and a bit of an oddity even for the Kota atelier. It consists of a schematic painting of a fort set at the edge of the lake. Only the walls and gates of the fort are sketched out, except for some lotuses blooming on the lake and a formal flower garden blazing with poppies and other herbaceous flowers within the fort walls. Hard to make out in full view images but very clear in one of Welch’s detail shots, a single banana plant rises amongst the flowers in one of the garden beds. This painting, though perhaps not quite as detailed and realistic as some of the previous examples, corresponds strikingly to a number of observations I make in my dissertation regarding a Sanskrit gardening manual. The Viśvavallabha of Cakrapāṇi Miśra, written around 1577 in the Kingdom of Mewar just to the west of Kota, stresses the planting of gardens inside forts, arguably in a reflection of local architectural realities. It is also unique among Sanskrit horticultural treatises in that it incorporates a number of temperate plants typical of Persianate gardens, many of them under their Persian names. Chief among these is the poppy, which predominates in the flower garden Shaykh Taju painted. The banana, meanwhile, is an Indian native and was a mainstay of Sanskrit gardening texts. As such, it became one of the first plants to be inserted in Persian gardening and farming manuals as they were recompiled and adapted for South Asia in the Mughal period. Shaykh Taju’s garden in its fort setting, then, exemplifies the convergence of textual and horticultural traditions my research traces in a single, poignant image, and serves as a perfect illustration to conclude one of my dissertation chapters.

Similar research possibilities await in the Stuart Cary Welch Islamic and South Asian Photograph Collection regarding myriad other topics. We strive to tag the image records thoroughly and strategically to make targeted searches as productive as possible. However, it is also worthwhile to just explore the collection. You never know what you might find.