This post is the fifth in a series about the Stuart Cary Welch Islamic and South Asian Photograph Collection written by the project’s staff and student catalogers in the Digital Images and Slides Collections of the Fine Arts Library. Written by Alice West.

The importance of our open access Stuart Cary Welch Islamic and South Asian Digital Images Collection has been noted in this series of blog posts. Yet, since the research, digitization, and cataloging of the collection is an on-going effort, we have not developed any systematic general description of this resource. But as the number of digitized images has grown, we have begun to define broad categories of images that could help researchers and art lovers around the world better understand what the Welch Collection can offer to them. This multi-part series from the project’s staff cataloger Alice West aims to highlight key strengths of the Welch Collection as a whole. In her first post, West describes one of the important subsets of the collection: works in private collections.

In this digital era, it may seem that anything one needs to find is readily available online. Yet researchers in any field, and in the field of Islamic art in particular, know that this perception is deceiving. Relative to the overall number of important Islamic manuscripts and artifacts, the number of their images available online or, for that matter, in print, is surprisingly low. There are many reasons for this, including shortage of technical and financial resources available for digitization efforts, as well as the unwillingness of institutions and private collectors to share their treasures with the public due to economic, political, ownership, and other concerns.

The Welch Collection fills in some of the ‘digital gaps’ by offering images from multiple sources that may not be otherwise available to the public. What are these gaps? One of the largest in terms of accessibility is private collections. Initially assembled for personal enjoyment, many prominent private collections from the late 19th–mid-20th century were later sold, bequeathed, or transferred to permanent hold to public museums and libraries. These include the collections of Calouste Gulbenkian, Victor Goloubew, Nasli Heeramaneck, Edmund de Unger, Leo S. Figiel, Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan, and many others. The majority of these collections have been fully or partially digitized by the hosting institutions. At the same time, many of the collections stayed private and are closed to the public eye. Although our digitization effort is not completed, we can already say that the Welch Collection holds hundreds of images of paintings, calligraphy, and decorative art that are currently held in otherwise inaccessible private collections, including that of B. W. Robinson, Bedros Sevadjian, Stuart Cary Welch, and many anonymous owners.

Periodically, objects from these collections are offered at auctions such as Sotheby’s or Christie’s, and one may find their images online or in older auction catalogs. These are, however, expensive and not widely available. Even when an image is available on the auctioneer’s website, Welch’s collection, in most cases, offers a superior image or its details (close-ups).

A Portrait of Raja Bhao Singh of Bundi. 18th century. Private collection. Detail. (Pic. 1a. Left: Photo: Sotheby’s. Pic. 1b. Right: Welch Collection)

An example of one such object is A Portrait of Raja Bhao Singh of Bundi, currently in a private collection. This portrait was sold in May 2006 by Sotheby’s, and its image is still available on the auctioneer’s website (1a. picture on the left). The Welch’s image, however, is obviously crisper and clearer in comparison, and its high resolution also allows for excellent close-ups (1b. picture on the right).

Divan of Hafez, Celebration of ‘Id. c. 1527, private collection. Full view (Pic. 2a. Left ) and detail (Pic. 2b. Right). Photo: Welch Collection.

Another example is Celebration of ‘Id from a dispersed Divan of Hafez, which is a relatively well-known miniature held by the private Art and History Trust of the Soudavar family and seen in several publications, most notably on the cover of Abolala Soudavar’s large volume of Reassessing Early Safavid Art and History. The Welch collection, however, offers quite a different look at this miniature by providing an amazing level of detail in its forty five unique high-resolution images of the miniature’s different sections (2a – 2d).

Pic. 2c. Divan of Hafez, Celebration of ‘Id. c. 1527. Detail. Photo: Welch Collection.

Pic. 2d. Divan of Hafez, Celebration of ‘Id. c. 1527, private collection. Detail. Photo: Welch Collection.

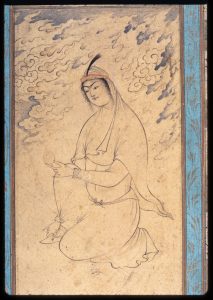

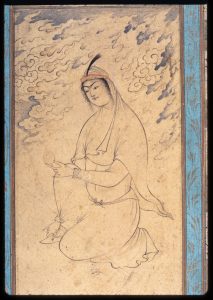

Of particular interest to researchers are the privately-held works that are not currently available to the public at all, as well as those that are only in limited professional publications as mere descriptions or, at best, as poor quality black-and-white photographs. The Welch Collection will be the only accessible repository where researchers can examine these objects in detail and in color. The beautiful Safavid album drawing below entitled Seated Girl, ca. 1600, is in a private collection in London (pic. 3). It is signed by Habib-allah of Mashhad, one of the artists in the court of Shah ‘Abbas the Great at Isfahan (Iran), and is an example of Habib-allah’s “faultless line,” and the elegant, flowing ease of the Safavid drawings [1].

Pic. 3. Habib-allah of Mashhad, Seated Girl. c. 1600, private collection. Photo: Welch Collection.

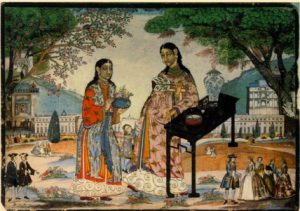

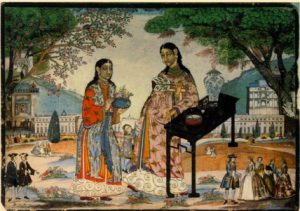

While our Welch Collection holds only one, full view, digital representation of Seated Girl, another picture from a private collection in Cambridge, MA, entitled Chinese Ladies in a French Chateau Garden, has twelve associated detailed images. Indeed, this painting abounds in different subjects scattered all over that warrant a closer look. Painted in the early 1800s in India, it is attributed, at least partially, to a Mewar artist Chokha and, according to Andrew Topsfield, represents “an anthology of borrowed European and Far Eastern themes, deriving from French fashion prints and mid-18th century Chinese export paintings …” [2]. A single low-resolution full view of this painting is featured in Topsfield’s paper (pic. 4a), but it is Welch’s collection that lets you explore it closer in twelve hi-resolution images of details (pic. 4b-d).

Pic. 4a. Chokha (attr.), Chinese ladies in French chateau garden. Early 19th century, Mewar, Rajasthan (India). Private collection, Cambridge, MA. Photo: Artibus Asiae.

Pic. 4b. Chokha (attr.), Chinese ladies in French chateau garden. Early 19th century, Mewar, Rajasthan (India). Private collection, Cambridge, MA. Detail. Photo: Welch Collection.

Pic. 4c. Chokha (attr.), Chinese ladies in French chateau garden. Early 19th century, Mewar, Rajasthan (India). Private collection, Cambridge, MA. Detail. Photo: Welch Collection.

Pic. 4d. Chokha (attr.), Chinese ladies in French chateau garden. Early 19th century. Mewar, Rajasthan (India). Private collection, Cambridge, MA. Detail. Photo: Welch Collection.

A popular image of Shah Jahan on the Peacock Throne exists in several versions, one of which is in a private collection. This particular painting with its beautiful margins featuring botanicals and birds is available through Wikimedia, but despite of its large size its details fall far behind the ones from of the Welch Collection (pic. 5b-d).

Pic. 5a. Shah Jahan on the Peacock Throne. 1634–1635, India, private collection. Detail. Photo: Wikimedia.

Pic. 5b. Shah Jahan on the Peacock Throne. 1634–1635, India, private collection. Detail. Photo: Welch Collection.

Finally, we would like to share with you a preparatory study titled Four Views of a Baby Elephant at Play from Stuart Cary Welch’s own private collection (pic. 6a-c). As a symbol of intellectual and mental strength in Hinduism and the Indian culture, elephants were a popular subject in Indian art. This baby elephant adorned with golden bells is painted with realism and grace characteristic of the Kotah drawing masters.

Pic. 6a. Four Views of a Baby Elephant at Play. c. 1720–1730, Rajasthan, Kota (India). Full view. Photo: Welch Collection.

Pic. 6b. Four Views of a Baby Elephant at Play. c. 1720–30, Rajasthan, Kota (India). Detail. Photo: Welch Collection.

Pic. 6c. Four Views of a Baby Elephant at Play. c. 1720–30, Rajasthan, Kota (India). Detail. Photo: Welch Collection.

To browse rare images from private collections assembled by Stuart Cary Welch, go to images.harvard.edu and in Advanced Search set Image Repository to “private collection” and Keyword Anywhere to “Welch”.

In subsequent blog posts in this series, we will continue talking about the different categories of images that one can find in the collection. As we continue to catalog these exciting (and open access!) images, we hope that whenever you search our collection, you will find just what you were looking for!

[1] Robinson, B. W. Picture Book of Persian Paintings. Victoria and Albert Museum, London, 1965, p. 17.

[2] Topsfield, Andrew. “Court Painting at Udaipur: Art under the Patronage of the Maharanas of Mewar.” Artibus Asiae. Supplementum, Vol. 44, Court Painting at Udaipur: Art under the Patronage of the Maharanas of Mewar (2002), p. 230.

This post inaugurates a new blog series written by the Welch project’s staff and student catalogers. Posts will contextualize how such a unique corpus of images made its way to the Harvard Fine Arts Library and will provide insight into what it’s like to prepare 65,000 slides for a new virtual existence online. To date, upwards of 10,000 Welch slides have already been scanned and published as digital images free to browse and download on

This post inaugurates a new blog series written by the Welch project’s staff and student catalogers. Posts will contextualize how such a unique corpus of images made its way to the Harvard Fine Arts Library and will provide insight into what it’s like to prepare 65,000 slides for a new virtual existence online. To date, upwards of 10,000 Welch slides have already been scanned and published as digital images free to browse and download on  It may or may not have come as a surprise to Welch, then, that his ‘innovative practice’ would become internationally mainstream over the next few decades. During the second half of the 20th century, university art history departments adopted the use of slides as a pedagogical tool. When digital media replaced analog image technology in the 1990s, these pre-information age collections started to take on new didactic roles beyond t

It may or may not have come as a surprise to Welch, then, that his ‘innovative practice’ would become internationally mainstream over the next few decades. During the second half of the 20th century, university art history departments adopted the use of slides as a pedagogical tool. When digital media replaced analog image technology in the 1990s, these pre-information age collections started to take on new didactic roles beyond t