(Draft 2; revised 2013/06/26)

Last week I was asked to join the Games for Change panel, “Games 2020”, and share some thoughts on the what the next few years might offer learning games from my perspective as Executive Director of iCivics. It’s a good time for reflection — we’re celebrating the 10th anniversary of the Games for Change Festival and Jim Gee’s seminal What Video Games Have to Teach Us about Learning and Literacy, and the ninth of Games+Learning+Society. iCivics has been along for half the ride, building what is arguably now the largest game-based curriculum in the country (18 games, 33K+ registered teachers).

Last week I was asked to join the Games for Change panel, “Games 2020”, and share some thoughts on the what the next few years might offer learning games from my perspective as Executive Director of iCivics. It’s a good time for reflection — we’re celebrating the 10th anniversary of the Games for Change Festival and Jim Gee’s seminal What Video Games Have to Teach Us about Learning and Literacy, and the ninth of Games+Learning+Society. iCivics has been along for half the ride, building what is arguably now the largest game-based curriculum in the country (18 games, 33K+ registered teachers).

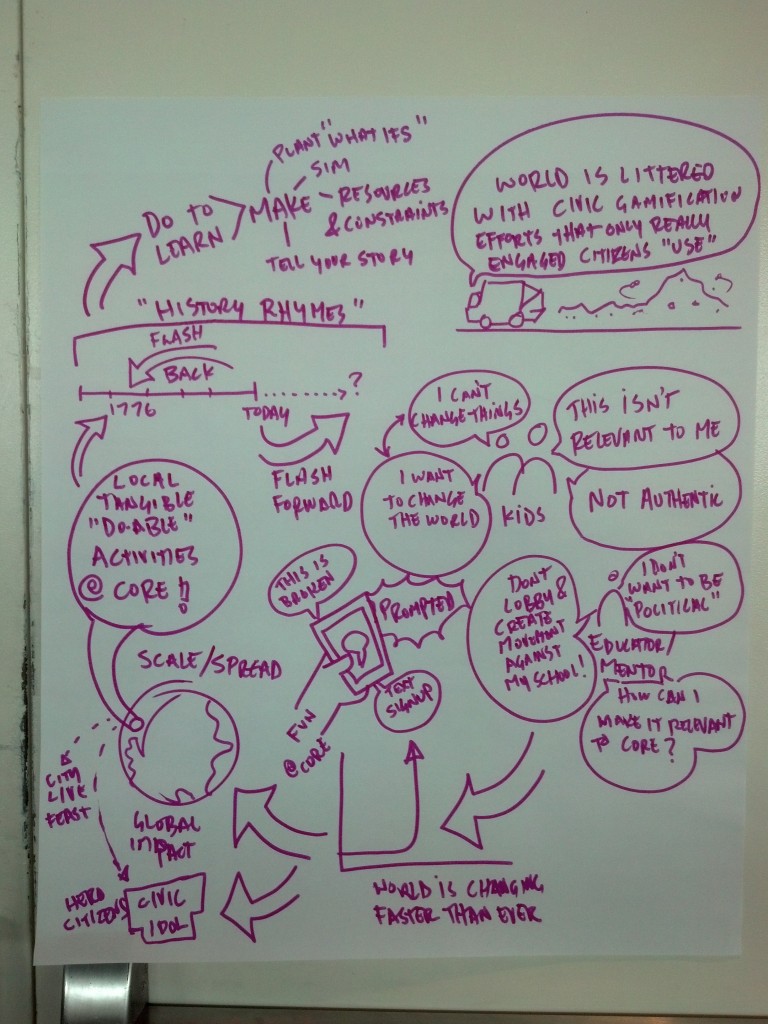

From our experience so far, there appear to be two major paths forward: games for learning and games for teaching. The two categories overlap but are not the same. They imagine different audiences, different deployment environments, and different imperatives:

Learning games target the consumer directly. They’re played “at home” (nowadays, that means anywhere). To players they provide entertainment or escapism, satisfy curiosity, and/or offer some sense of agency.

Teaching games target the consumer indirectly, through an intermediary educator who’s also the primary customer. Like other teaching resources, they must demonstrate effectiveness (in developing knowledge, skills, or dispositions), meet standards and requirements, and be usable by teachers either standalone or with available training and support.

Of course, the best teaching games are also learning games. I’ll call this sweet Venn spot “educational games.” It’s nice to imagine that it’s a big target, but unfortunately experience suggests that it’s not.

Concept art for “Do I Have a Right?”

Here’s a concrete example of how these two categories diverge.

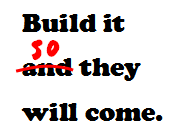

Do I Have a Right? is iCivics’ most popular game, with over 2 million game plays over four years. Part of the reason for its success is that we optimized it for classroom use: it’s browser-based and needs only Flash installed, students can complete it in under 30 minutes, and they can play 1:1 or share computers. (Many of our teachers project the game via Smartboard to the whole class at once). Despite the hoopla over iPads in schools, it seems most of the users of our iOS version of the game,

Pocket Law Firm, play for entertainment or edutainment. The feedback we’ve gotten reflects that audience’s interests: When are you adding more levels? Can we get more in-game loot? Why does the game peter out at 40 minutes?

On the flip side you have SimCity, the AAA entertainment title from EA/Maxis. Alongside Oregon Trail, SimCity is probably one of the most-cited examples of a learning game, especially because it’s a sandbox featuring complex, interacting systems. As a major commercial title, the latest version was built with consumers in mind (complaints notwithstanding). The potential to teach gamers key concepts in economics, urban design, public policy, and environmental science is tremendous. But the same features that make it a AAA title also make it unusable in the vast majority of schools: it requires software installation, because it requires serious graphical horsepower, and because it must always stay online (with considerable bandwidth requirements). GlassLab, an Institute of Play project, has invested heavily in adapting the game for classroom use by developing scaffolded scenarios for STEM topics. I hope these investments will not only make SimCity a better learning game, but also more accessible to schools.

So learning games aren’t necessarily teaching games. However, the very best teaching games should also be at least good learning games — that is, satisfy the needs of both students and teachers. Note that I write “student,” not “consumers” or “youth.” It is, I admit, a much easier user to satisfy. The competition is not “Call of Duty” or “Walking Dead.” It’s textbooks.

Educational games find a balance between teacher needs and interests, and student needs and interests. They also find a balance between supporting and challenging schools as we find them. Challenge schools too much with technical requirements or massive reworking of pedagogy, and scaling will be a tough road to walk. Accommodate the school environment too much, and you’re back at the maligned edutainment / disguised-multiple-choice-quiz that pervaded the previous generation of educational games.

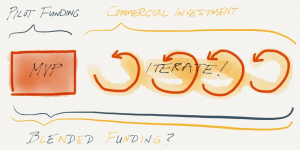

If great educational games are to thrive, we need new investments in the coming years:

1. We need better information and research about games that succeed for student learning. We’re already seeing major efforts here with Common Sense Media’s ratings for parents and the forthcoming Games and Learning directory from the Games and Learning Publishing Council.

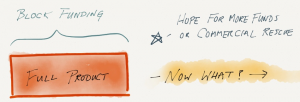

2. We need developers to pay more attention to the needs of teachers and not just students, and for founders/investors to underwrite these additional requirements. Let’s be clear here: it’s probably more expensive to develop games that are good for both students and teachers. Though, in iCivics’ experience, not necessarily that much more.

3. We need marketplaces that support these products so we can run sustainable businesses that can continue to support, evolve, and innovate these products.

What if we try all of this and find that the best learning requires sophisticated games that can’t be utilized in today’s schools? I suppose you do as Katie Salen did and open new ones, or as Jim Gee does and advocate for better school systems (and a fairer society). But let’s not go straight to the near-impossible task of remaking the system as our first impulse. Let’s see if we can hack them first with educational games that push towards better teaching and learning.

Takeaway: One of the fastest and cheapest ways to win a big audience for your new game is through a well-connected partner. It’s a lot easier to win partners when your product fits their interests and business model – and that needs to be built into your plans from the outset.

Takeaway: One of the fastest and cheapest ways to win a big audience for your new game is through a well-connected partner. It’s a lot easier to win partners when your product fits their interests and business model – and that needs to be built into your plans from the outset.