Most games play on a narrow range of human emotion, rarely straying from excitement, anxiety, or awe. So it’s worth noting when a game comes along that relies on a rather unusual feeling for an entertainment title: guilt.

(In using the term “guilt,” I am primarily drawing on our colloquial understanding of the term, the feeling of conflict between what one has done and what one believes one should have done, rather than any specific psychological or philosophical definition. I suspect much of our understanding of the word “guilt,” outside of the law, comes from marketing for diet products).

If Wii Fit succeeds in whipping American butts into shape, it will partially be through imparting a feeling of obligation to do some exercise every day. But it also courts danger in this regard: a nagging game can turn off a would-be exerciser as easily as its non-interactive predecessors. (How many treadmills became bulky clothes racks after the heat of zeal congealed into lethargic shame?). Serious commitments require both a carrot and a stick, but too much stick kills the fun.

Wii Fit employs a smörgåsbord of characters to engage players: there’s your Mii avatar, the diagram-y yoga instructors, and the anthropomorphized Wii Fit balance board. While the Mii gives some basic feedback (its shape changes as you gain/lose weight) and the yoga instructors provide tips and positive feedback, it’s the balance board that helps you set and keep your goals and chides you when you go astray.

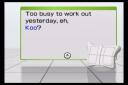

The balance board character, a strangely expressive white rectangle, is no match for the average mom, but skip a day or two and does serve up a “You don’t call, you don’t write” routine:

There’s no reasoning with the board on this matter. Go on a week-long business trip? Too bad – that smug little rectangle doesn’t offer excuse options. On the other hand, neither does it dwell, moving on with perfect cheer and letting bygones be bygones. Unlike a true nag, it never brings up your transgression again — the prick of guilt is instant and ephemeral. But it is there.

So Wii Fit, via the balance board character, “cares” whether you play with it or not, and whether you do so regularly. (Once you start, the game tracks but doesn’t mind which exercises you choose). A game that makes you feel guilty for ignoring it isn’t novel; pet simulators like Nintendogs also mark your absence, during which time your virtual puppy gets increasingly hungry, thirsty, and disheveled. The possibility of neglect, and the guilt that accompanies it, seems to stimulate some sense of care and responsibility.

Wii Fit doesn’t merely concern itself with your decision to play; as an interactive title that attempts to change the user, it also attempts to address your other, probably more important choices. Consider this sequence, triggered when you gain too much weight vis-à-vis your stated goal:

We’ve often discussed reflection as a vital element of moral choice-making in games. On the scale of moral choices, staying healthy isn’t high up there (except for the ancient Greeks), but this device of asking the player to reflect on out-of-game, real-life decisions is worth considering for application in other games for change. Particularly notable is that it’s the player, not the software, who sets the goals in the first place. The Wii Fit is there to help keep you on the path that you’ve laid down for yourself.

Is this method of reflection effective as a mechanism for personal change? Or does it, together with the goal-setting and the nagging, only drive away those who have trouble staying on the bandwagon? We should start seeing some answers in the next few months.

– Gene Koo

When we first fired up

When we first fired up  The University of Chicago’s Joshua Correll has created a basic first-person shooter to advance his research into how race influences life-and-death decisions like

The University of Chicago’s Joshua Correll has created a basic first-person shooter to advance his research into how race influences life-and-death decisions like