I’ve been pondering how the concept of spectacle fits in with surveillance. In particular, I’ve been bouncing around two different concepts of the spectacle, one by Michel Foucault and the other by Scott Bukatman.

Here’s an execution spectacle in Michel Foucault’s Discipline & Punish:

‘Finally, he was quartered,’ recounts the Gazette d’Amsterdam of 1 April 1757. ‘This last operation was very long, because the horses used were not accustomed to drawing; consequently, instead of four, six were needed; and when that did not suffice, they were forced, in order to cut off the wretch’s thighs, to sever the sinews and hack at the joints… (Foucault 75)

Here’s a science fiction spectacle (William Burrough’s death dwarf in Nova Express) in Scott Bukatman’s Terminal Identity:

“Images — millions of images — That what I eat — Cyclotron shit — Ever trying kicking that habit with apormorphine? — Now I got all the images of sex acts and torture ever took place anywhere and I can just blast it out and control you gooks right down to the molecule — I got orgasms — I got screams — I got all the images any hick poet ever shit out — My power’s coming — My power’s coming — My power’s coming. … And I got millions of images of Me, Me, Me meee.” (Bukatman 45)

Foucault’s Discipline & Punish describes an arc from disciplining society through the use of public executions as spectacle to disciplining society through the more complex interaction of an array of civilizing institutions (prisons, schools, hospitals, factories, etc) and their various agents (guards, judges, experts, teachers, etc). Foucault argues that the spectacles were effective insofar as they represented an imposition of the king’s body onto the body of the public, and at the same time provided space for the condemned to voice their frustrations against the monarchy. This system of disciplining the public began to break apart as the power of the people grew and consequently the king’s symbolic body lost power relative to the body of the people, which is to say that the increasingly powerful public was able to question the fairness of the terrifying executions and the one sided prosecutions that led to them.

What eventually replaced these spectacles, Foucault argues, was the modern set of institutions whose most important impact was to embed discipline into the social fabric itself, rather than imposing discipline bodily through bloody spectacle. Prisoners, pupils, patients, and workers (as examples) learned that they were being watched continuously and that their fates were judged by a set of scientific criteria which were themselves defined by the system of watching. Instead of investing all power in the prosecutor, the modern judicial system invests its power into the jury’s ability to objectively judge the truth of various pieces of witness and scientific testimony. The guilty man is condemned not because of the will of the king but because our objective system determines him to be guilty. If you don’t want to be judged guilty, you have to judge yourself by this objective criteria, rather than by the arbitrary decisions of the king. And if you want to succeed in school or at work, you have to measure up to objective criteria. But those objective criteria are themselves influenced by this process. Experts prune themselves for their work in court, social institutions design the tests that determine school success, and so on.

What’s interesting to note is that Foucault described in 1975 a move away from spectacle and to this more complex and subtle integration of the scientific and the social as a means of social discipline. In 1994, Scott Bukatman’s Terminal Identity captured a widely held consensus that television and other mass media had once again made spectacle the dominant mode of social discipline. Bukatman pulls together a set of social theorists, media thinkers, and science fiction authors to describe a “terminal space” in which a flood of image, audio, and text “blips” constitute a never ending spectacle through which society defines itself. This image of society as spectacle contrasts sharply with the image drawn just twenty year before by Foucault. And the spectacle has multiplied itself many times with the explosive growth of the Internet since 1994, including the growth of Internet pornography and YouTube beatings that make Burrough’s death dwarf (above) look prescient.

To figure out what this move away from and then back to spectacle means, we first have to figure out what “spectacle” means and whether Foucault and Bukatman are referring to the same thing at all. Foucault’s spectacle of execution and Bukatmans’ (and others’) spectacle of mass media both refer to a display of striking images. The public execution is striking largely because it is dramatically physical. One cannot watch a execution without a strong, physical reaction. Bukatman’s flood of images (and other media) is striking partly because each image is designed for emotional impact (buy this SUV if you want to dominate the road) but mostly because of the sheer number of images. It is striking to be shown many different images at once, even if each image is just as a single solid color. Foucault’s spectacle is striking because it is so strongly physical, whereas the modern media spectacle is completely virtual — it is a spectacle because of the sheer flood of input that cannot be reproduced bodily. Bukatman argues that the lack of physicality actually defines the media spectacle as such: “pure spectacle … [is] … a proliferation of of semiotic systems and simulations which increasingly serve to replace physical human experience and interaction.” (Bukatman 26) Most importantly, both of these spectacles are used a source of control over society, and the impact of each form of spectacle relies on the dramatic impact of the spectacle itself — this need for dramatic impact is why, for instance, modern executions by injection serve nothing like the role of the spectacular public executions that Foucault describes. In contrast to the slow diffusion of the social knowledge through institutions, spectacle derives its power from its ability to reach directly into the brain of its subjects and create an immediate reaction (who wants to argue over which textbook a school should use when you can just make a YouTube video and beam your truth directly into kids’ brains?).

Coming back to surveillance, both of these forms of spectacle (like institutional discipline) involve not just being watched, but watching as well. The spectacle of execution is an application of watching onto the public: not only does the execution enact the punishment of the kind on the body of the people, but the process of prosecution applies the eye of the king onto the people. By watching and judging the condemned, the king is making clear that he is watching the public, both symbolically and through his state apparatus. The watching and being watched of this process are necessarily entangled: one cannot have a public execution without a prosecution, and the prosecution has no social impact if it is not in turn watched.

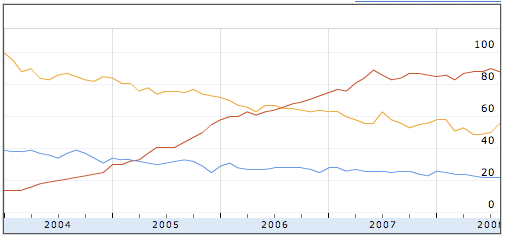

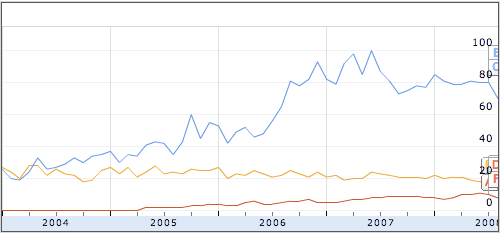

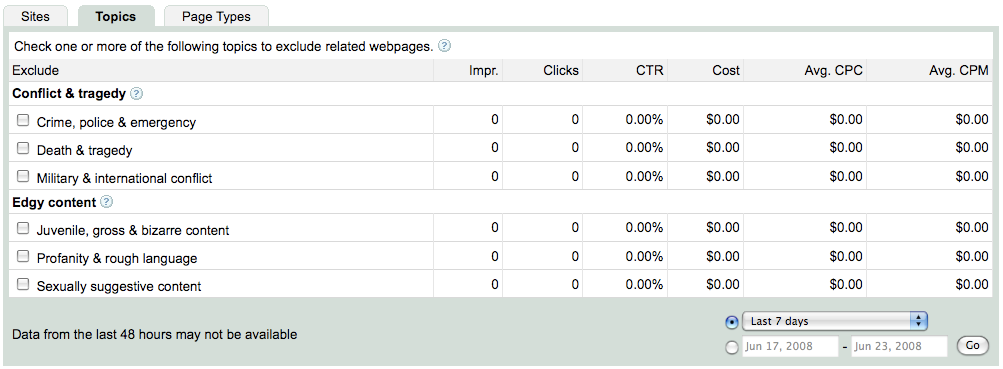

The modern media spectacle provides an even more tangled relationship between watching and being watched. Much of the modern spectacle is advertising, which is about pushing images to consumers to get them to watch them. But advertisements are only useful if the advertiser knows who is watching them. Television ratings and commercials are necessary complements, as are clicks and web advertisements. An advertisement (and any spectacle used as a social lever) is only useful insofar as its impact can be measured, and knowledge of who is watching an ad is necessary to measure that impact. This tangled relationship between watching and being watched applies not only to the advertiser and the consumer, but quickly spreads out into the whole range of different actors involved. The content provider watches which ads are most profitable and watches which content brings consumers to its ads, the ad brokers like google watch both consumers and advertisers to determine which ads are most valuable and profitable, the various participants in the botnet economy watch (or pretend to watch) the ads to game profits while also watching google to determine how to avoid its click fraud filtering, search engine optimization (SEO) agents of various levels of legitimacy watch google to improve their customers’ positions in the google index, security professionals of various sorts watch the botnets to learn how to protect against them and watch users to determine if they are infect or likely to get infected, and on and on. Every one of these actors is both watching and being watched, and each one is a necessary growth of the system that begins with the simple display of an image intended to leverage some sort of social control. It is impossible to say which actors are merely being watched and which are watching, just as it is impossible to point to any activity that does not involve both watching and being watched by multiple actors.

What’s different between execution as spectacle and media as spectacle is that executions are hard to repeat, whereas each of the little images that together make up the media spectacle are easy to produce. Today, production and distribution of these images on the Internet has become virtually free, so anyone can produce these images, and they are ominpresent in the media (online, tv, etc). But this ease of production makes the effects of the spectacle much, much less clear. Foucault argues that the execution as discipline ended largely because it began to grow network effects that the king could not control, and that was just from a single producer of generally infrequent spectacles. The result of the proliferation of spectacle producers today is a hugely complex network, briefly sketched above, whose effects are mostly emergent and unpredictable. When anyone can leverage control through a spectacle, everyone does, but those effects all bounce off of one another in complex feedback loops. Foucault describes a similar effect in his institutional disciplinary society, but the effect in his case involves far fewer major players and is therefore much less complex. Today anyone can create a spectacle to influence society (buy a car, vote for my candidate, scream, laugh, cry).