Before there was Napster

The battle between copyright-holders and pirates is frequently in the news these days, but it has a history just as long as publishing itself. Eighteenth century verse satirist Peter Pindar (the pseudonym of John Wolcot) was particularly troubled by the depredations of pirates, since he had no other income but that which he derived from his poems. Pindar’s poems were a particularly tempting target for pirate printers, since they were short, highly topical lampoons of public personages.

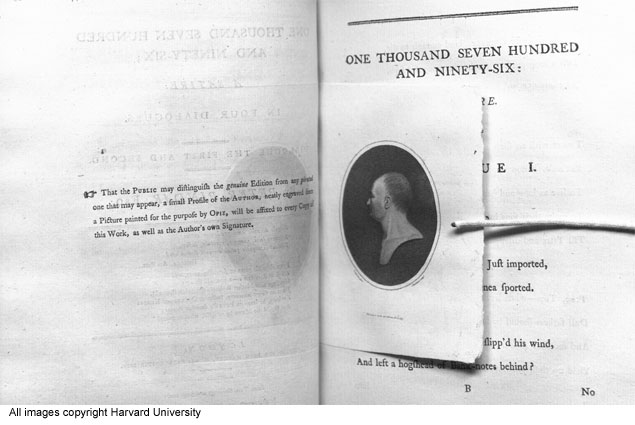

Pindar’s first anti-piracy effort came in 1788 in the form of a notice that “The proprietors of the works of Peter Pindar, Esquire, find themselves obliged, on account of frequent piracies of his productions, to offer ten guineas reward, on the conviction of any offender; the money to be immediately paid by the publisher, and the name or names of the communicating party concealed.” The effectiveness of this bounty at stopping the pirates can be gauged from the fact that by his next publication, it had been raised to twenty guineas. Eight years later, Pindar and his publishers tried a different tactic, having Pindar autograph every copy of his poem One Thousand Seven Hundred and Nintey-Six, no easy task for someone whose works sold in the tens of thousands. In addition, a small engraved portrait of the author was attached to each copy to identify it as geniune, no doubt driving up the expense of production considerably. Of course, as today’s movie studios could tell you, identifying geniune copies only helps if your customers want to avoid the pirated ones.

For much more on the relationship between Peter Pindar, his publishers, and the pirates, see Satire is a Bad Trade by Donald Kerr

Both comments and pings are currently closed.