Russia Labeled “Partly Free” in 2009 “Freedom on the Net” Report

July 14th, 2009 — idteamBy Karina Alexanyan

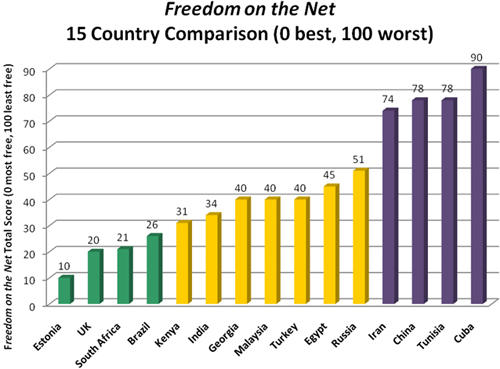

Freedom House recently released a report examining emerging tactics of government control of digital media, with a focus on 15 countries around the world, including Russia. The report, “Freedom on the Net”, concludes that increasing digital media access and use worldwide is accompanied by more systematic and sophisticated methods of control.

The countries examined were Russia, China, Iran, Brazil, Cuba, Egypt, Estonia, Georgia, India, Kenya, Malaysia, South Africa, Tunisia, Turkey and the UK.

All Images: Freedom On the Net

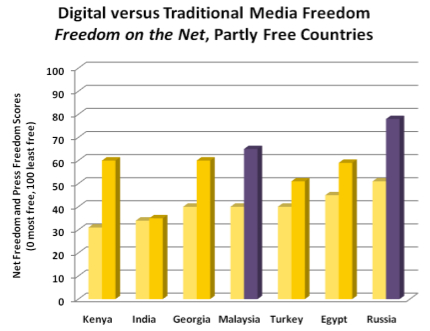

The key positive findings of the report suggest that poverty is not necessarily a barrier to new media freedom, that civic activism is growing around the world and that, in many cases, internet freedom exceeds press freedom. On a negative note, there is a continued lack of transparency and accountability, growing legal threats and technical attacks, and an increase in forms of censorship.

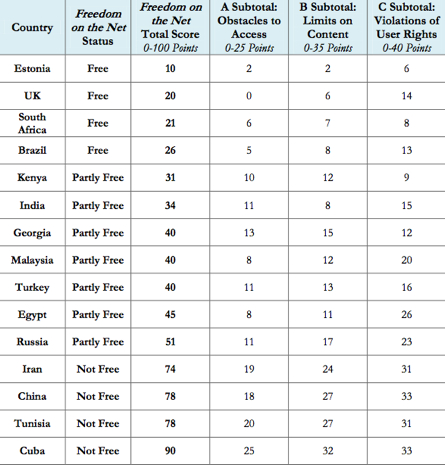

The report is organized around a Freedom on the Net index, which scores each country on a scale of 1-100, based on three main categories – Obstacles to Access (governmental, legal, infrastructural & economic), Limits to Content (various forms of censorship and content manipulation, diversity of online news media, and usage of digital media for activism) and Violations of User Rights (legal protections and restrictions, privacy violations and various legal and physical repercussions for online activity).

Based on these parameters, Russia is labeled “Partly Free” with a total score of 51. Specifically, Russia’s scores are:

Obstacles to Access – 11 out of 25

Limits to Content – 17 out of 35

Violations of User Rights – 23 out of 40

The Russia section of the report begins by positioning the internet in Russia against the elimination of independent television channels in 2000-01 and the tightening of press regulations, labeling it “the last relatively uncensored platform for public debate and the expression of political opinions”.

First bar: Internet; Second Bar: Traditional Media

Yellow=Partly Free; Purple=Not Free

At the same time, the report points out that “many Russians view the internet as a proper sphere for governmental control.” According to a Levada-Center poll taken in December 2006, almost half the population would either “absolutely agree” or “rather agree” with the statement “It’s time to bring order to the internet.”

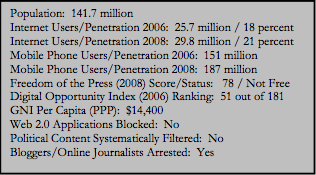

The report concludes that, while there is little overt technical blocking or filtering in Russia, the legal environment has become more threatening, and there are increasing cases of sophisticated “soft censorship” (described in more detail below) and a rising number of attacks or threats to internet activists and bloggers. Russia joins other “Partly Free” countries like Egypt and Malaysia as a case where “government encouraged improvements in access to ICTs and relatively little censorship are offset by harsh legal environments, state monitoring and a rise in criminal prosecutions.”

The main “Obstacles to Access” in Russia are infrastructural (such as the lack or expense of broadband outside the large cities) rather than authoritative.

In terms of “Limits on Content,” the report details various degrees of censorship which display a move away from overt “strong arming” to more subtle techniques of diversion and confusion, designed to misinform the public and subvert or discourage debate. These include tried and true methods such as “telephone pressure” where government officials call “owners, shareholders, and anyone else in a position to remove unwanted material and ensure that the problem does not come up again.” “After receiving such calls,” the report continues, “managers and editors are more likely to practice self-censorship.“ More sophisticated methods involve “forum trolling” by paid bloggers and government affiliated volunteers, as well as the practice of swamping blogs with oppositional accounts of various sensitive incidents. Straightforward propaganda websites have given way to a proliferation of Kremlin-affiliated “content providers” with a vast network of online websites and information that collectively dominate search results, among other effects. As the report explains, “if an opposition or grassroots organization starts its own internet platform, Kremlin-related groups will launch several that are similar in form, if not in content. These sites create confusion among users by adopting similar imagery, slogans, and names.” As a result, despite Russia’s vibrant blogosphere, the report finds that “blogs do not have a major influence on political life….due less to the apathy of Russian web users than to the government’s success in preventing online activism from spreading to the streets or reaching wider media audiences. “

The report also suggests that the close ties between the owners of online business and the Russian government can threaten internet freedoms. For example, the Kremlin-affiliated oligarch Alisher Usmanov owns significant stakes in all three of Russia’s top social networking sites– LiveJournal, Odnoklassniki and Vkontakte. The report argues that because the business magnates are “eager to maintain good relations with the Kremlin” they are “more likely to resort to various nontransparent practices to ensure that their web services are free of objectionable material or activity.”

According to the report, conditions for user rights in Russia have significantly worsened since 2006. Bloggers have become subject not only to hacker attacks but also to physical violence and legal prosecution. Over the course of the study, one internet activist was killed, seven criminal cases were launched against bloggers, one blogger was badly beaten, and ten oppositional blogs were attached by hackers.

As the report explains, “although the constitution grants the right of free speech, there are no special laws protecting online modes of expression, and even constitutional guarantees are routinely violated. Online journalists do not possess the same rights as regular journalists unless they register their websites as mass media. Recent police practice has been to target online expression using Article 282 of the criminal code, which restricts extremism. The term is vaguely defined and includes xenophobia and incitement of hatred toward a social group”. In a recent case, a 23 year old blogger was sentenced to one year of probation using this code. The “social group” in question was the police.

According to the report, Russia has the technology to access and analyze internet traffic (similar to what the FBI uses in the US) as well as legislation that allows the government to intercept data traffic without a warrant. As yet, no cases of the use of this system have been reported. In 2008, the FSB announced the creation of a new portal to monitor the Russian internet and mass media, ostensibly in order to monitor public opinion.

Click Here

Click Here

July 15th, 2009 at 11:44 am

The comment about free speech is interesting. It seems in Russia, online journalists are not guaranteed the rights that regular journalists are, while here in the United States online journalists or bloggers seem to get away with way more?

July 20th, 2009 at 6:54 pm

[…] Alexanyan of Internet & Democracy Blog accounts for Russia labeled partly free in a recent Freedom House report on Freedom on the Net. Cancel […]

July 21st, 2009 at 3:03 am

[…] Alexanyan of Internet & Democracy Blog accounts for Russia labeled partly free in a recent Freedom House report on Freedom on the […]

July 22nd, 2009 at 11:35 am

I’m not sure that the monitoring is necessarily the problem. It is the repercussions from being caught nay-saying the govt. The fear of reprisal prevents free journalism. If you know that you can be monitored, then why post or write at all.