UPDATE: I would like to address a question that was asked of my research project. The 30 blogs used were found within the South African blog directory Amatomu. Specifically, I used a group of highly-read blogs under the “Life” section of the directory. I chose this portion of blogs (as opposed to business, news, technology, or sport blogs) because personal diary weblogs seem to be pertinent to the study of social behavior in cyber spaces. I also utilized a smaller number of blogs found within the blogrolls of the Amatomu grouping. Lastly, I used Afrigator, another digital media directory, to locate other bloggers within the South African blogosphere. Thanks everyone for the interest and comments on the research.

In his article “The Daily We”, Cass Sunstein proposed a theory of Internet polarization that has sparked interesting dialogue among cyber philosophers. Essentially, Sunstein argues that while the web has demonstrated its potential to democratize public discourse, the habits of its users also feeds a kind of balkanization. Empirically, research has shown how individuals tend to navigate toward online content that fits within their own spheres of interest and opinion, creating a fragmented and polarized net. Sunstein explains, “Not surprisingly, many people tend to choose like-minded sites and like-minded discussion groups. Many of those with committed views on a topic—gun control, abortion, affirmative action—speak mostly with each other.”

Adamic and Glance tested this theory in their frequently cited article, “The Political Blogosphere and the 2004 U.S. Election: Divided They Blog,” in which they analyzed the degree to which liberal and conservative networks overlap. It is perhaps just as telling to explore how different races and ethnicities interconnect in cyber spaces. Within a heterogeneous blogosphere, will we observe polarization and segmentation along racial, ethnic, or linguistic lines or will we observe an integrated network, whereby linking behavior is, largely, colorblind? I undertook a short research project to address this question, using the South African blogosphere as my empirical field. South Africa is a fitting candidate for such analysis, as it is a racially mixed society—comprised of blacks of Bantu descent, whites of European ancestry, Indians and Malay persons, and “Coloured” persons of mixed black and white descent. Interestingly, South Africa is as fractionalized linguistically as it is ethnically. The “rainbow” nation has eleven official languages, including the widely-used Zulu (isiZulu), Xhosa (isiXhosa), Afrikaans, English, and many other less prominent languages of specific ethnicities.

In this study, I examined three sectors of the South African blogosphere specifically—English-speaking white bloggers, black bloggers, and Afrikaner bloggers. I utilized the blog search engines Technorati and Blogpulse as well as the South African blog directory, Amatomu, to conduct my analysis. I surveyed approximately 30 blogs in each sector.

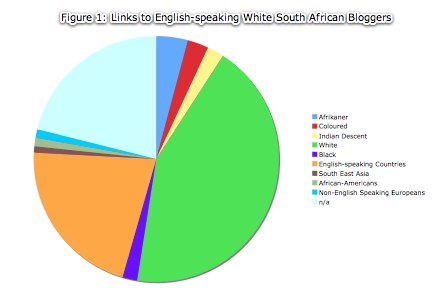

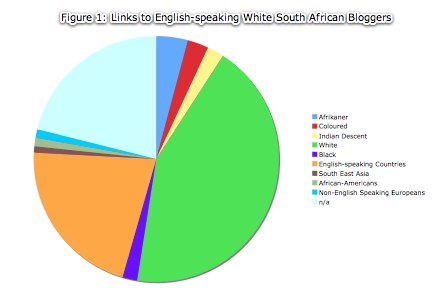

English-speaking white bloggers make up the largest and most trafficked portion of the South African blogosphere. After analyzing this sector of the network, I have found evidence that this portion of the blogosphere is rather segmented. A majority of English-speaking white bloggers link to other English-speaking white bloggers within South Africa or in other industrialized democracies. Within the examined group, 43 percent of links originate in blogs authored by other English-speaking white South Africans, while 21 percent of links come from blogs authored by whites in other English-speaking nations, including the U.S., U.K., Australia, and New Zealand. 6 percent of in-site links originate in the blogs of Afrikaners within South Africa, and 2 percent of the links are from South African bloggers of Indian descent. 4 percent of in-site links originate in blogs authored by Coloureds in South Africa, while only 2 percent derive from South African blacks. Finally, 2 percent of these in-site links originate in non-English speaking European blogs, 2 percent came from South East Asian bloggers, and 1 percent derive from the blogs of African-Americans in the U.S. I was unable to determine the race and ethnic background of 21 percent of the blogs I examined, which were then coded as “n/a.”

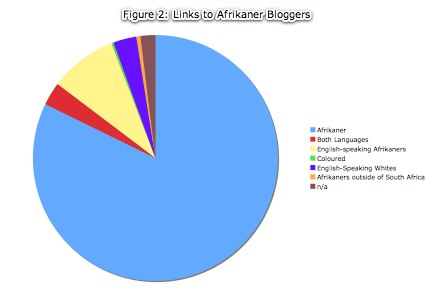

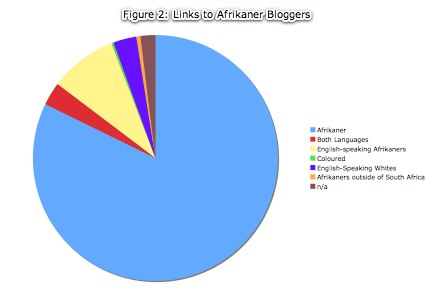

In this study, I also analyzed a group of Afrikaner blogs. The Afrikaans blogosphere, like the English-speaking white sector, is also considerably large. However, of each South African group examined, Afrikaner bloggers were, by far, the most isolated group in the greater network. 83 percent of the links in these blogs originate in other Afrikaner blogs. 3 percent of links come from bloggers who utilize both Afrikaans and English in their online diaries, while 9 percent of these links originate in the blogs of ethnic Afrikaners who choose to blog solely in English. Only 3 percent of the links examined derive from non-Afrikaans bloggers in South Africa, and less than 1 percent of links originate in blogs authored by South African Coloureds. Lastly, 0.5 percent of these links came from Afrikaner bloggers residing in countries other than South Africa (such as Canada and Australia).

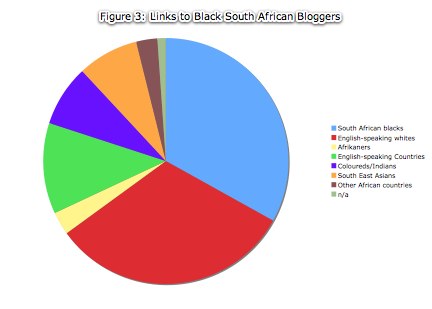

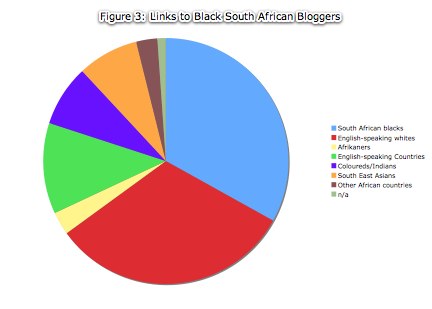

The last sector examined was the South African black blogosphere. Black bloggers make up the smallest portion of the South African network, and many blogs reported no in-site links when entered into Technorati and Blogpulse search engines. Nonetheless, the black blogosphere was the most integrated of the three groups examined, as nearly the same portion of in-site links in this sector originate in the blogs of English-speaking whites as in blogs authored by South African blacks. Of the group examined, 33 percent of links originate in blogs authored by other South African blacks, while nearly 32 percent of links derive from the blogs of English-speaking whites within the nation. Twelve percent of in-site links are from bloggers, both black and white, in industrialized democracies like the U.S. and U.K. 8 percent of the links originate in blogs authored by Coloureds and/or Indians within South Africa, and another 8 percent of links are from bloggers in South East Asian countries, like India, Philippines, and Indonesia. Lastly, 3 percent of these links derive from other African bloggers outside of South Africa, and another 3 percent of the links examined originate in an Afrikaans blog.

Despite this breakdown, a word of caution is warranted. Due to the small size of the South African black blogosphere, these results are somewhat skewed. Although nearly 32 percent of in-site links originate in the blogs of South African whites, it appears that only a handful of blogs are feeding this integration. According to Technorati search results, 56 percent of those whites who linked to the black blogosphere did so to Living Bridget, an active black blogger in South Africa. Indeed, the small number of black bloggers in South Africa limits the ability of Technorati and Blogpulse in reporting blog reactions. Perhaps stronger indicators of linking behavior on the black blogosphere are the individual blogrolls of each online diary. A preliminary look at these blogrolls indicates that black bloggers tend to link primarily to the weblogs of other South African blacks.

This study has found support for Sunstein’s theory of Internet balkanization, by illustrating how South African netizens tend to associate with others of similar racial and ethnic backgrounds, whether they be in South Africa or abroad. It remains a question as to whether linking behavior within cyberspace reflects real-life social relations or if this type of segmentation is only an artifact of web-based forums. Nevertheless, it is socially relevant to consider how races and ethnicities interact online in South Africa because the implications of polarized cyberspaces in this nation could, in fact, be harmful.

In recent years the Rainbow Nation has experienced a host of social, economic, and political troubles that have rocked this young democracy. Corruption, widespread violence and crime, and xenophobic attacks (mostly fueled by conditions of pervasive poverty and inequality) are only some of the problems that face South African citizens. If the online public sphere is indeed balkanized, an opportunity for effective dialogue to address these problems will be missed. Sunstein comments, “Without shared experiences, a heterogeneous society will have a more difficult time addressing social problems and understanding one another.” Perhaps the next step in this research would be to analyze if and how online forums are addressing social problems in South Africa. It is likely that one will observe either pertinent and effective communication among vested and diverse parties or, in a worse case scenario, another “Daily We.”

Click Here

Click Here