Internet Filtration in the Middle East

August 13th, 2009 — Scott HartleyThis week the OpenNet Initiative (ONI) released its 2009 report on Internet filtration across the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). Research for this release was conducted in 2008-2009, but it builds upon findings dating back to 2003, including a report released in 2007. The full release (available in PDF) chronicles the detailed testing of over 2,000 websites in each country. The ONI’s work on Internet controls in the region provides crucial context for the Internet & Democracy’s work on the networked public sphere.

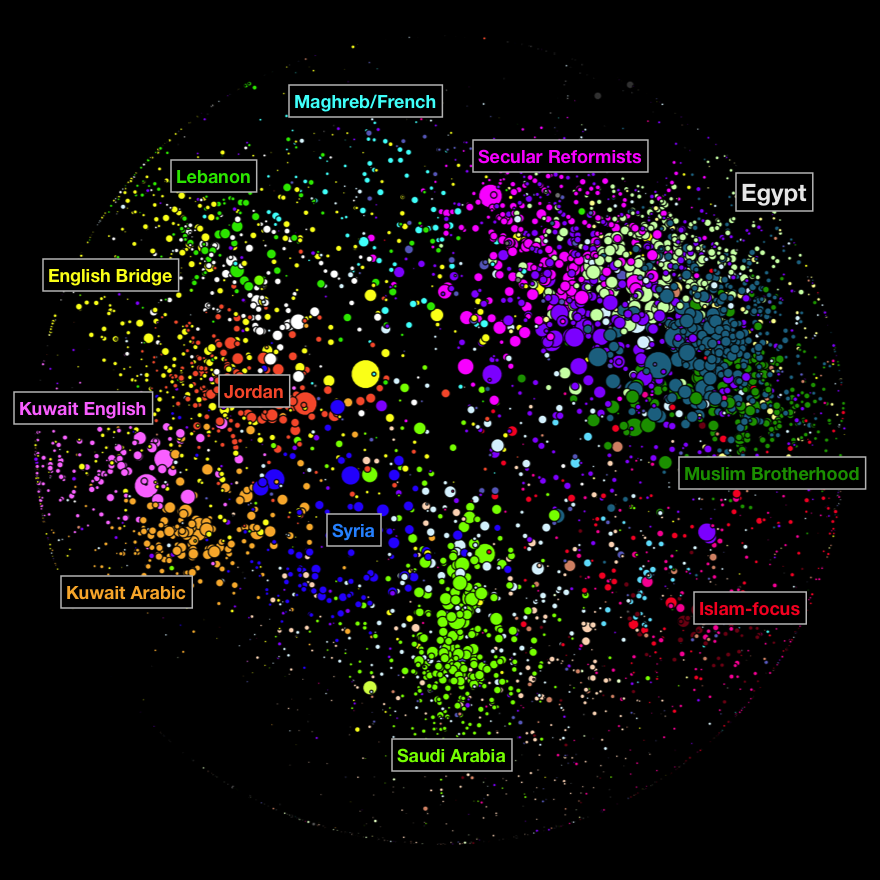

Back in June, the Internet & Democracy team released a study of the Arabic Blogosphere, authored by John Palfrey and Bruce Etling of the Berkman Center, and John Kelly of Morningside Analytics. The research spanned 35,000 Arabic language web logs across 18 countries in the Middle East. A few weeks ago, the United States Institute of Peace (USIP) released the webcast, including the interpretations by three panelists Daniel Brumberg of Georgetown University, Acting Director of USIP’s Muslim World Initiative, Saad Ibrahim of Voices for a Democratic Egypt, and Raed Jarrar, a prominent Iraqi Blogger who writes Raed in the Middle.

Here’s a quick rundown on the conversation at USIP:

In June, 150 viewers from 26 countries –with the highest Middle East representation coming from Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon– watched the presentation of the Arabic Blogosphere study for at least 30 minutes, and many asked challenging questions of the researchers via Twitter and chat. The research findings proved not only illustrative, but also provocative.

Saad Ibrahim of Voices for a Democratic Egypt, expressed a predominantly Egyptian perspective, highlighting blogs as indicative of youth perspective, and youth’s centrality in Egyptian demographics. He discussed the “electronic unveiling” of Saudi women, the protective “tribalism” displayed by Egyptian bloggers, and the fact that “Egypt today is the online voice of Iran.” Commenting on the study’s findings, Ibrahim declared that the Egyptian blogosphere is witnessing a new age, where “issues and technology” dominate the political online discourse, and where “bashing the U.S. is not a pastime” so much as an occasional necessity.

Daniel Brumberg of Georgetown University and Acting Director of USIP’s Muslim World Initiative discussed the role of the Internet in “globalizing moderates, and marginalizing militants,” pointing out that bloggers were overwhelmingly critical of both extremist tactics and United States interventions. He discussed the importance of blogs in bridging between conflicting parties, noting that authoritarian regimes are usually less nervous about criticism inside “walled gardens” than cross-cluster talk. Beyond discourse, he elucidated the importance of political and social institutions, demographic understanding, and context to frame blogger perspectives.

Raed Jarrar, a prominent Iraqi Blogger who writes for Raed in the Middle, critiqued some of the study’s findings. He maintained that the choice of many Iraqi bloggers to write in English is dictated by the political realities of “foreign occupation” rather than personal preference. He was additionally critical of the study’s research framework, taking issue with the parlance of labels such as “moderates” and “militants,” “secular reformists” and “Muslim Brotherhood.” Furthermore, he pointed out the “inherent bias” in investigating Arabic blogs’ support of “terrorism” or “extremism,” positing that “resistance” might be a more uniformly understood term for “terrorism” in the Arab world. He argued that the map would appear very different with re-framed parameters – for example, a different set of political categories could be seen across geographic or religious lines if attentive clusters were bifurcated by demographic understanding. Similarly, new patterns would emerge from categorizing bloggers by their political agenda rather than their religious affiliations.

During the question and answer section, the study methodology was further elucidated, and the incorporation of Arabic speakers and regional experts explained. The researchers also responded to questions regarding shortcomings in the study’s choice of parameters and labels, emphasizing that their focus was primarily on understanding the digital discourse phenomenon, and providing a set of tools to study it. Categorizations will always be crude approximations of a reality far more complex than can be conveniently articulated – it is important though to be aware of these limitations and draw conclusions commensurate with such approximations.

Several questions centered on the relation between the Arabic blogosphere and transnational and local media, and by extension, the connection between online life and real life in the Arab world. The researchers said it is hard to estimate the extent to which Arabic blogs reflect public opinions or consensus views, though they pointed out that Al Jazeera, the BBC and Al Arabiya are the top three mainstream media sources linked to by Arabic bloggers. In answer to the question “does online discussion distract from activism?” panelists called for a more careful analysis of who is blogging and who has access to the Internet. Jarrar for example stated that the Iraqi online discourse is “not mature enough to have its own mobilization.” Brumberg said that one of the biggest challenges ahead is to get bloggers to move to the public and political spheres.

Participants wanted to know if the study’s findings could be read as evidence for the Internet Balkanization, as “similarly minded publics are being tied with similarly minded publics.” The national clusters that emerge in the Arabic blogosphere do seem to reflect an increasing focus on local issues. Others wanted to understand how this study compared with studies in the West, and if so whether the perspectives of the Western blogosphere matched Western social attitudes, questioning the assumption that online discourse can be extrapolated to understand larger societal trends. Yet others wanted to more comprehensively understand the linkages between online discourse and offline events, and how discourse percolated through and impacted the functioning of domestic institutions.

While some called the research Western centric, broad participant consensus was that an analytical Pandora’s box had been opened, and its understanding was both vital and daunting. Perhaps most importantly, one participant asked, “We now know who’s writing, but what about who’s reading online?”

Manal Dia, a Berkman Center Researcher & MIT graduate student, contributed to this post.

Click Here

Click Here