Illuminated: Evolution in my Understanding of Islam through the Arts

In a class I am taking at the school of design, the professor concluded with a statement regarding the future of urban planning and of humanity as it relates to the ever-evolving smart city platform by saying, “The most profound technologies are those that disappear. They weave themselves into the fabric of everyday life until they are indistinguishable from it.” While the conception of profound technology as having this unique quality of being able to interweave itself with humanity is very intriguing, I think that it has been preceded by many millennia in the form of religion — another large, amorphous entity which has successfully been able to weave itself into the fabric of everyday life until it is largely indistinguishable from it. It constructing this blog, in attending lecture, in participating in section, in casually absorbing the art and sound and literary spolia taken from various islamic traditions, islam — via “For the Love of God and His Prophet” — has ever-so-quietly integrated itself into the fabric of my everyday life.

I began my blog with the intention of sticking to a visual and spiritual sort of motif surrounding the concept of light and God as light (al-nur) in the islamic tradition. I was heavily borrowing ideas directly from previously existing artistic and literary canon, as that was what I — trained from an academic and critical background — knew how to do. However, this concept readily evolved — for the better, I believe — to a more creative, immersive, and self-driven one as I learned more about the various ways in which islam could be expressed and interpreted (and as I was gently prompted by Armaan and Professor Asani to rely more on my own sense of creativity rather than making creative reinterpretations of previously existing artistic forms). One of the key turning points for the evolution of this personal understanding of islam and the arts occurred when I attended the Conference of the Birds dance workshop, where our class learned how we could integrate the unseen — storylines, thoughts — with the seen — the movements of our physical bodies.

The Conference of the Birds dancers created storylines from where before there was nothing. These dancers naturally expressed emotions in accordance with these storylines and connected to each other seamlessly without a single word being uttered. Even more amazingly, perhaps, was the way in which first-time dance participants were able to demonstrate this same ability — connecting seamlessly to one another without words and creating storylines where before there were none. Being able to have this experience radically transformed my conception of islam in that it directly showed me how the physical and the spiritual should not be conceived of separately, as they share a single plane of existence. To expound upon this, I would like to further analyze the way in which the physical and the spiritual come to coexist within various practices of islam.

There is a strong presence of the physical aspect in islam, especially in the form of ritual and perhaps most readily apparent in the Five Pillars of Islam. Physicality pervades all of the Five Pillars of islam, the five acts most necessary to being considered a muslim, which are widely considered to be the meter by which one’s life as a muslim is measured: the shahada (or the declaration of faith wherein one states that there is no God but God and that Muhammad is the messenger of God), the salah (the ritual of cleansing oneself and praying five times a day by moving through various positions — standing, bowing, and prostrating), zakat (the act of alms-giving), sawm (fasting — most notably from sun up to sun down during the month of Ramadan, but also all forms of ritualistic fasting), and finally, the Hajj (an annual pilgrimage which muslims seeking higher spiritual enlightenment make to the holy city of Mecca, where they complete another series of rituals). It is worth mentioning that these Five Pillars do have some variation throughout various iterations of the islamic faith, however, it is my understanding that this physical component, regardless of tradition, is always present in worship in islam. While the coexistence of the physical with the spiritual is able to be seen in all forms of Islam in the practice of the Five Pillars, it is perhaps most apparent in Sufi Islamic traditions, which more readily seek the unification of the physical with the spiritual.

In Sufi Islam, muslims attempt to personally experience the divine love and knowledge of God. It my understanding that Sufis adhere even more readily than other muslim practitioners to the Five Pillars of Islam — practicing these rituals devoutly. Sufis, however, more than practicing these rituals, seek to cultivate their spiritual relationship with God through contemplation and international reflection, often with the assistance of a teacher and often culminating in the production of various art forms, like art, poetry, or music. The visible physical expression of the spiritual experience seems to occur more often in Sufism. One such visual that comes to mind is the video we watched in one of Professor Asani’s lectures of a Sufi ritual in an African mosque: In the video, everyone was dressed similarly — in green, with white turbans — and everyone was moving in a way that signified that they were all one figure, while reciting the shahada. While I have cited examples of the linkage between the spiritual and physical in islamic worship practices in varying traditions, I think that, given the importance of the the Quran itself to the islamic faith, that it is necessary to turn to the scripture itself.

There is a particular passage from the Quran that seems to me to be very important when considering the inextricably-linked spiritual and physical practices of islam. I quoted this passage once previously in my blog posts, but it is so significant to my evolved understanding of islam that I believe it warrants mentioning again:

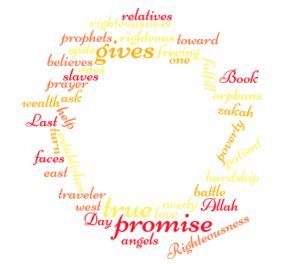

“Righteousness is not that you turn your faces toward the east or the west, but [true] righteousness is [in] one who believes in Allah, the Last Day, the angels, the Book, and the prophets and gives wealth, in spite of love for it, to relatives, orphans, the needy, the traveler, those who ask [for help], and for freeing slaves; [and who] establishes prayer and gives zakah; [those who] fulfill their promise when they promise; and [those who] are patient in poverty and hardship and during battle. Those are the ones who have been true, and it is those who are the righteous.” — [2:177]

This passage — to me, although I am not sure that I am qualified to perform any form of tafsir, or interpretation of God’s will — stresses that Islam cannot be considered to be something which is either exclusively physical or exclusively spiritual. Islam in its true form must be both physical and spiritual. It is my sincere hope that the viewer or reader of my blog posts will be able to glean this same understanding of Islam through their consumption of said posts.

Because of the evolution in thought that has accompanied my journey through this course, my blog posts are highly variant in content and form. The older posts are more limited to interpreting Islam in a binary way — a physical form is created and analyzed through a spiritual lens. However, I think that the newer posts are more successful in conveying the coexistence of physicality and spirituality that I have previously explained. To break down these posts a little more succinctly, the viewer of my blog will find:

- A brief overview of my original intentions in creating and naming my blog, Illuminate. This post is helpful when read in conjunction with this essay in terms of understanding my personal transformation of thought from the beginning of this course to the end of this course.

- The calligram project wherein I reproduced a small-scale infinity mirror to reflect the light of God in a niche into eternity, as is referenced in Surah 24:35, which, abridged states that “Allah is the Light of the heavens and the earth. The example of His light is like a niche within which is a lamp, the lamp is within glass, the glass as if it were a pearly [white] star lit from [the oil of] a blessed olive tree, neither of the east nor of the west, whose oil would almost glow even if untouched by fire. Light upon light.”

- A study of the geometries used in mosque arabesque, a form of decorative pattern stemming from plant scroll imagery and incorporating various figurative geometries and colors, as well as my personal discovery that artisans of the past were exceptionally talented in their ability to maintain symmetry in their creations.

- My visual interpretation of the Isra and Mir’aj, Muhammad’s “Night Journey,” the journey he took to the farthest mosque to give a sermon as well as his ascension to the heavens to speak with God, in chalk pastel.

- An admittedly very ugly rendition of a green sun to represent the Shi’a belief of the hidden 12th imam in watercolor.

- A sort of East-meets-West interpretation of a literary ghazal (without musical accompaniment or form) through the lens of unrequited or unfulfilled love inspired by characters in Ernest Hemingway’s “The Sun Also Rises.”

- What I call an “Islamic Tonal Experiment,” where I show my creation of a short song on the piano in the harmonic A minor scale (Arabian scale) to characterize the spiritual journey of the individual in islam, as well as to highlight the potential collective undertones of this individual journey within islam in a greater context.

- My very fun interpretation of an “Acapella Hip Hop Adhan,” utilizing the Acapella App, which seeks to abstract the muslim call to prayer while adding elements popular in contemporary African American Islamic musical practice.

- A visual demonstration of a world cloud, which takes key terms from the Surah passage I quoted earlier in this essay, Surah 2:177, and combines the power of word with the power of sunrise/sunset imagery within the geometric figure of a circle.

While my artistic merit in many of these blog posts is potentially somewhat lacking, I think that its downfalls showcase the way in which Islam is something which can be celebrated and enjoyed by everyone — regardless of their ability or station in life.

Overall, I found this blog posting process to be very enjoyable and important to my own understanding islam through the lens of the arts. It is subsequently my hope that all readers and viewers of this blog will be able to take away even a modicum of this same understanding — the inextricable link between the physical and spiritual in the practice of islam, especially as that practice relates to artistic practice.

I personally think that, in reflecting on my class experience and in potentially speaking to students out there who might be reading my essay and considering whether or not they should take this course, it is also important to note that, while my main takeaway from this course was strongly linked to Islam and the arts, that this class also touched on very important topics as they relate to history, geopolitics, and the study of gender dynamics. Specific instances that occur to me are the topic of the Islamic Revolution in Iran, the Wahhabi takeover on the Arabian peninsula, and the question of the Hijab as a marker either for or against women’s rights. These topics might better serve as potential areas of interest for those students who may not consider themselves oriented towards the arts but who have an avid curiosity in the the study of Islam and how it relates to the world at large.

In concluding my blog, I would also like to extend an extra note of gratitude to all those involved in this course this semester. Professor Asani, Armaan, the dance workshop leaders, and my fellow classmates all helped to cultivate a learning environment which I feel is wholly unique on this campus. It has been a privilege to be able to learn from and with you.

Thank you!

Recent Comments