On June 11, signals for the Hellenic Broadcasting Corporation, known as ERT, went silent. Immediately after the government-ordered blackout, Greek journalists, many of whom had just lost their jobs, staged a 24-hour strike, refused to leave ERT headquarters, and continued to report the news on the Internet through the European Broadcasting Union, which is maintaining ERT’s radio and television frequencies via live stream on the EUB website.

Stating that ERT needed to save money and restructure, Prime Minister Antonis Samaras’s government suspended operations at the public network (comprised of 19 regional channels, four national channels—one that broadcast abroad—six radio stations, a TV guide magazine, websites and the national audiovisual archives). Plans were announced to reopen later in 2013 under the new name Hellenic Radio, Internet, and Television (NERIT). A blogger at Troktiko said in a news report, “We registered the domain name www.nerit.gr as soon as the new name was announced.” The blog’s name means rodent in Greek and is a popular news source in Greece with an intriguing history and a reputation for hard-hitting investigative journalism.

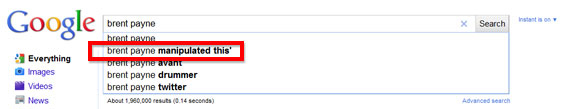

Screen shot from www.NERIT.gr on June 12. “It’s not just about ERT, it’s about democracy.” Photo credit: Leigh Graham

Members of the Greek blogosphere were delighted and amused with the news, suggesting the government’s failure to register the domain name before publicly announcing it showed “how pathetic they are.” Internet users visiting NERIT.gr, before it was surreptitiously taken down, received live stream news, a ghoulish meme face, and the message: “It’s not just about ERT, it’s about democracy.” They were also redirected to the blog pitsaria-pou-eskise. This blog’s name is a riff on Samaras’s suggestion in an interview last year that his business experience running a pizzeria during his college days in America had prepared him to run the country. Pitsaria pou eskise is a colloquialism and translates roughly as “the pizzeria did extremely well or was a massive hit.” Samaras’s awkward attempt to relate to the people was quickly picked up by bloggers and turned into a taunt. NERIT.gr has been taken down, but pitsaria-pou-eskise.gr is still up and doing extremely well.

The days following the shutdown may have been a score for Greek netizens; yet, citizens on the ground were shocked and suffering. More than 2,500 people lost their jobs, and many people living in rural villages and remote islands where ERT is the sole source of outside information were cut off from current news as well as cultural programming.

The blackout of a national broadcaster, massive layoffs, and the isolation of entire communities of citizens are troubling events, and both professional and citizen journalists swiftly responded with collective voice and clear demands. Internet-based citizen media has been developing in Greece for a while. Radio Bubble is a good example. Operated out of a café in Athens, it is a mixed-media network of websites, radio channels, blogs, Twitter, and other online sources that blurs boundaries between being a member of a community on the Internet, on the air and on the streets. In classic power-to-the-people style, Radio Bubble exists to report underreported news in real time through the unfiltered lenses of tech-savvy, everyday activists. Radio Bubble also runs a program called Hackademyteaching citizen journalism skills such as using smartphones to interview and document real-time events, using laptops to edit films, and using social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter to post real-time reporting. Hackademy also offers courses on how to verify stories and authenticate sources.

Thousands of demonstrators gather after Greece’s government announced the ERT closure. Photo credit: AFP/ Louisa Gouliamaki

In light of political corruption and economic turmoil presently crippling the country, many Greeks have lost faith in traditional media. Though many favor cuts in the public sector, including trimming within the notoriously mismanaged ERT, they are not pleased with the way things were handled. Aristides Hatzis, associate professor of law, economics and legal theory at the University of Athens told reporters “the ERT debacle illustrates the government’s lack of respect for the rule of law.” In response, Greek citizens took to the streets in protest, and unions launched a strike that throttled transportation and everyday business. Their outrage also filled Internet channels.

In addition to galvanizing local citizens and members of the Greek diaspora, online reporters, Twitter users, and bloggers relentlessly demanded redress from Prime Minister Antonis Samaras. To this end, both citizen activists and opposition parties have achieved some gains. On June 17, ERT was ordered to reopen but has not resumed broadcasting. The EUB website reports, “The Council of State ordered the Greek government to restore the ERT signal and take all appropriate organizational measures to continue broadcasting through the ERT frequencies and Internet sites until a new public service broadcaster is established.” Ramifications from the ERT shutdown and stalled reopening are sure to play out for weeks, months, maybe even years to come. The outcome remains to be seen; however, one thing is certain: the Internet and citizen media have been irrevocably cast as lead actors in Greece’s continuing political drama.

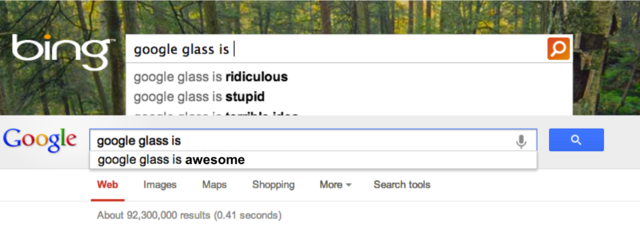

Xbox One isn’t the only product to have an interesting mix of autocomplete suggestions. Autocomplete on Google suggests “google glass is stupid” and “google glass is creepy.” Bing suggests these too, but also suggests that google glass is: “ridiculous,” “[a] terrible idea,” “military tech,” “scary,” and “useless.”

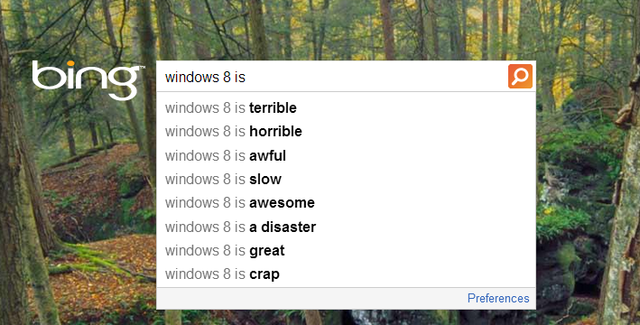

Xbox One isn’t the only product to have an interesting mix of autocomplete suggestions. Autocomplete on Google suggests “google glass is stupid” and “google glass is creepy.” Bing suggests these too, but also suggests that google glass is: “ridiculous,” “[a] terrible idea,” “military tech,” “scary,” and “useless.” Searching for other tech companies returns interesting results, too. Google suggests that “apple is”: “dying,” “evil,” “dead,” and “doomed,” while Bing suggests the company is: “evil,” “losing its cool,” “losing,” “a cult,” “dead,” and “going downhill.” (On the flip side, Bing’s autocomplete also suggests that Apple is a “good company to work for” and “better than android.”) Meanwhile, Bing’s autocomplete doesn’t seem to be advertising Windows 8 very well, suggesting that “windows 8 is:” “terrible,” “horrible,” “awful,” “slow,” “awesome,” “a disaster,” “great,” and “crap.” These are only a few of the latest examples, but

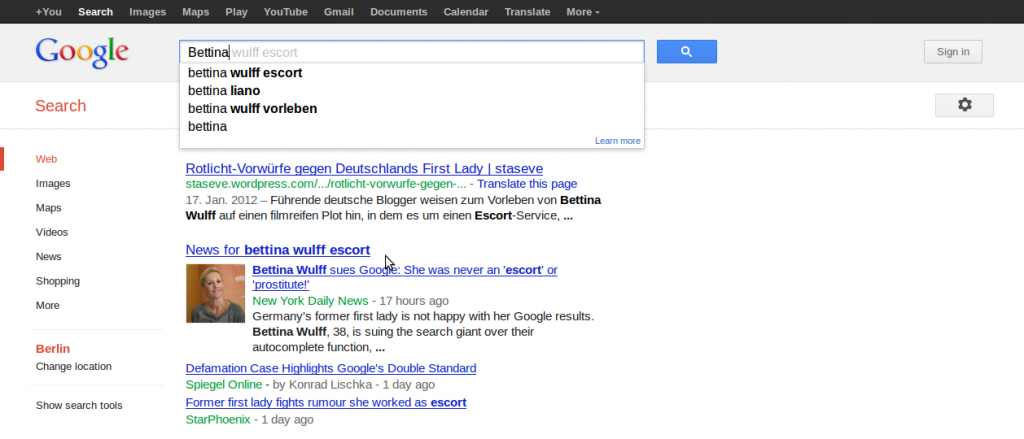

Searching for other tech companies returns interesting results, too. Google suggests that “apple is”: “dying,” “evil,” “dead,” and “doomed,” while Bing suggests the company is: “evil,” “losing its cool,” “losing,” “a cult,” “dead,” and “going downhill.” (On the flip side, Bing’s autocomplete also suggests that Apple is a “good company to work for” and “better than android.”) Meanwhile, Bing’s autocomplete doesn’t seem to be advertising Windows 8 very well, suggesting that “windows 8 is:” “terrible,” “horrible,” “awful,” “slow,” “awesome,” “a disaster,” “great,” and “crap.” These are only a few of the latest examples, but  But what if a person’s name is autocomplete associated with something they might not like? In May 2013, former first lady of Germany

But what if a person’s name is autocomplete associated with something they might not like? In May 2013, former first lady of Germany  Before Wulff, Google’s main defense had been,

Before Wulff, Google’s main defense had been,