Bill Froberg/Flickr

Modern editions of Mary Shelly’s Frankenstein often drop Shelly’s 1818 full title for the celebrated novel, which reads, Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus. The Prometheus legend has several variations, but Shelly’s story draws more upon Aesop’s version of the story, in which Prometheus makes man from clay and water. Prometheus’ creation, which violated the process for how life is naturally made, rebels against him, and Zeus punishes Prometheus for the unintended consequences of his act.

Last week, The Atlantic reported that Google and Bing seem to be autocompleting different stories about Microsoft’s upcoming game console the Xbox One. On Google, a search for “the Xbox One is” returns autocomplete suggestions for “terrible,” “ugly,” and “a joke.” The same search on Bing, Microsoft’s flagship search engine, returns a single autocomplete suggestion: “amazing.” Commentators on the Atlantic article pointed out that dropping the term “the” from the searches would yield different results and should put to rest any conspiratorial thinking that Google is smearing Microsoft’s product using its autocomplete. A search for “xbox one is” on Google is still pretty negative, suggesting “xbox one issues,” “xbox one is bad” and “xbox one is garbage.” However, Bing’s suggestions are even more scathing. When dropping “the,” Bing seems to agree with Google suggesting “xbox one issues” and “xbox one is bad.” However, it also suggests that Xbox One is “terrible,” “going to fail,” “ugly,” “watching you,” “crap,” and “doomed.”

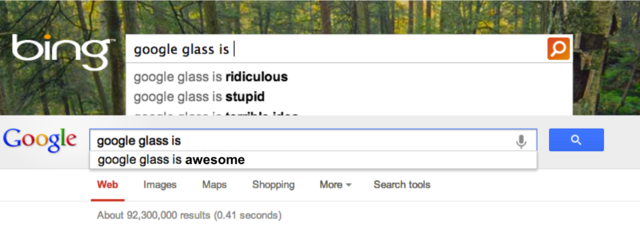

Xbox One isn’t the only product to have an interesting mix of autocomplete suggestions. Autocomplete on Google suggests “google glass is stupid” and “google glass is creepy.” Bing suggests these too, but also suggests that google glass is: “ridiculous,” “[a] terrible idea,” “military tech,” “scary,” and “useless.”

Xbox One isn’t the only product to have an interesting mix of autocomplete suggestions. Autocomplete on Google suggests “google glass is stupid” and “google glass is creepy.” Bing suggests these too, but also suggests that google glass is: “ridiculous,” “[a] terrible idea,” “military tech,” “scary,” and “useless.”

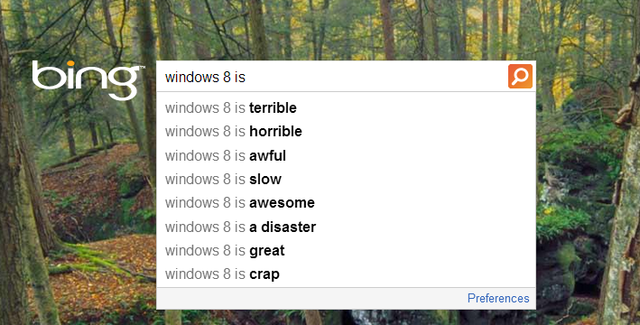

Searching for other tech companies returns interesting results, too. Google suggests that “apple is”: “dying,” “evil,” “dead,” and “doomed,” while Bing suggests the company is: “evil,” “losing its cool,” “losing,” “a cult,” “dead,” and “going downhill.” (On the flip side, Bing’s autocomplete also suggests that Apple is a “good company to work for” and “better than android.”) Meanwhile, Bing’s autocomplete doesn’t seem to be advertising Windows 8 very well, suggesting that “windows 8 is:” “terrible,” “horrible,” “awful,” “slow,” “awesome,” “a disaster,” “great,” and “crap.” These are only a few of the latest examples, but FAIL Blog has a great collection of similar autocomplete fails collected by search engine users.

Searching for other tech companies returns interesting results, too. Google suggests that “apple is”: “dying,” “evil,” “dead,” and “doomed,” while Bing suggests the company is: “evil,” “losing its cool,” “losing,” “a cult,” “dead,” and “going downhill.” (On the flip side, Bing’s autocomplete also suggests that Apple is a “good company to work for” and “better than android.”) Meanwhile, Bing’s autocomplete doesn’t seem to be advertising Windows 8 very well, suggesting that “windows 8 is:” “terrible,” “horrible,” “awful,” “slow,” “awesome,” “a disaster,” “great,” and “crap.” These are only a few of the latest examples, but FAIL Blog has a great collection of similar autocomplete fails collected by search engine users.

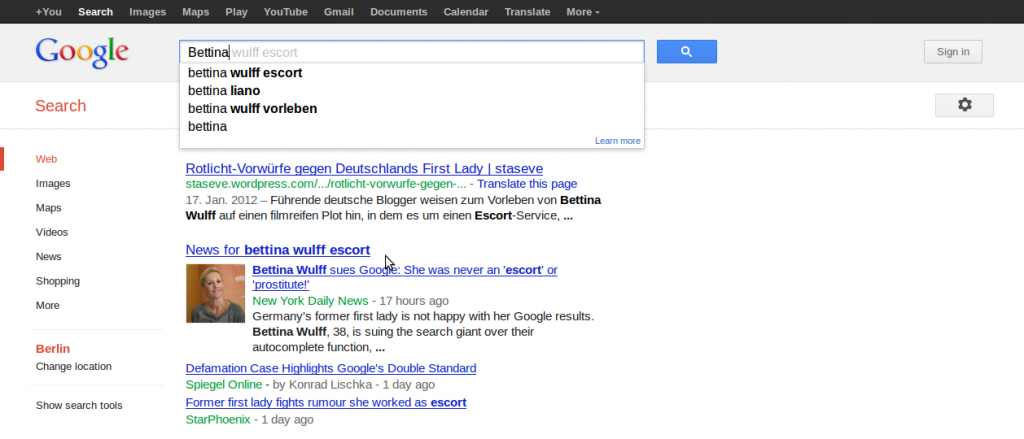

But what if a person’s name is autocomplete associated with something they might not like? In May 2013, former first lady of Germany Bettina Wulff successfully sued Google for automatically completing search terms entered into the company’s German search engine that associated her name with “escort,” “prostitute,” or “past life.” For years, rumors had been circulating that Wulff had worked as an escort before meeting her husband (and future president) Christian Wulff. Five similar autocomplete cases have been leveled against Google in Germany, most of which involve associations between a person’s name and terms like “fraud” or “bankruptcy,” and before Wulff, Google had won them all.

But what if a person’s name is autocomplete associated with something they might not like? In May 2013, former first lady of Germany Bettina Wulff successfully sued Google for automatically completing search terms entered into the company’s German search engine that associated her name with “escort,” “prostitute,” or “past life.” For years, rumors had been circulating that Wulff had worked as an escort before meeting her husband (and future president) Christian Wulff. Five similar autocomplete cases have been leveled against Google in Germany, most of which involve associations between a person’s name and terms like “fraud” or “bankruptcy,” and before Wulff, Google had won them all.

Before Wulff, Google’s main defense had been, as explained by the company’s Northern Europe spokesperson Kay Oberbeck, that the predictions come from “algorithmically generated result of objective factors, including the popularity of the entered search terms.” Google argued it was not responsible for simply displaying the mass input of users, but even if German courts had agreed, the marketing departments have some serious work ahead of them.

Before Wulff, Google’s main defense had been, as explained by the company’s Northern Europe spokesperson Kay Oberbeck, that the predictions come from “algorithmically generated result of objective factors, including the popularity of the entered search terms.” Google argued it was not responsible for simply displaying the mass input of users, but even if German courts had agreed, the marketing departments have some serious work ahead of them.

Despite Google’s assertions that “autocomplete predictions are algorithmically determined based on a number of factors (including popularity of search terms) without any human intervention” and that “objective factors” alone drive the suggestions, Google voluntarily and expressly intervenes in autocomplete results to remove hate speech, copyright infringement, and other terms on a country by country basis (for example, searches in German do not show Holocaust denial keywords, but they do appear in searches within the US). While Google had not lost an autocomplete case in Germany before Wulff, it had lost several defamation cases in Japan, Australia, and France.

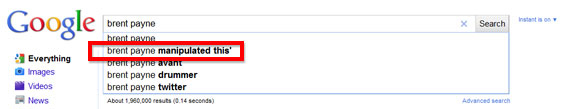

And what if some clever person figured out how to use autocomplete to their advantage? In 2010, Internet marketing expert Brent Payne paid several assistants to search for “Brent Payne manipulated this.” Not long after, users typing “Brent P” into Google would see Payne’s results in their autocomplete suggestions. When Payne advertised what he had done, Google removed the suggestion.

idesignwebsitesnet/Flickr

Payne’s manipulation of Google’s autocomplete and Google’s own reaction should indicate that the algorithms built to guide and direct us through the Web are neither infallible nor incorruptible. In several countries, algorithm creators have been held responsible for the actions of their autocompleting creations. At the same time, decisions to intervene in the operation of algorithms can be viewed as censorship or an abuse of power. Shelly borrowed the term “Modern Prometheus” from Immanuel Kant’s description of Benjamin Franklin’s contemporary experiments with electricity. When the creators of algorithms can be held responsible for the defamation of their creation, by legal institutions or consumers, those creators are forced to accept the successes, limitations, and failures of their experiments with electronic discourse.

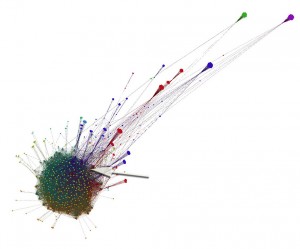

Diaspora:

Diaspora: App.net:

App.net: Tent.io:

Tent.io: GlassBoard:

GlassBoard: Identi.ca:

Identi.ca: