Prologue

Upon entering the course, “For the Love of God and his Prophet: Religion, Literature, and the Arts in Muslims Cultures”, I hoped to gain a foundational understanding of the Islamic religion and how its interpretation and practice has been shaped throughout history. By studying Islam through its art and literature, I was able to achieve this familiarity that I had wished for at the outset of the semester. As I reflected on my learning in order to create these blog posts, I decided to focus on aspects of the course that allow for discussion of the relative degrees of continuity and divergence within the faith. It was striking to me that despite the constant interaction between religion, history, politics, and cultural standards, which would inevitably lead to innumerable renditions of the Islam worldwide, some of the most important early Islamic, and even pre-Islamic traditions and beliefs have prevailed throughout the religion’s long history.

In particular, the rich history of poetry, which dates back to pre-Islamic times, has been maintained throughout recent times. In fact, three of my blog posts, “The End of an Era”, “Wine, Roses, and Nightingales, Oh My!”, and “They see the Simorgh-at themselves they stare”, are reflections upon a specific work or genre of Islamic poetry. Another continuity in the religion that illuminates the blog posts stems from the first. Accompanying this traditional emphasis on poetry is the prevalence of and appreciation for oral recitation. The lyricism of poetry makes it conducive to oral performances, but above anything, memorization and recitation of the Quran is the most highly valued. It is in this realm of worship that the true beauty of text and of the religion can be realized. Quran recitation is also unique because it allows both the performer and the listeners to connect deeply with the text. This aspect of continuity is especially relevant to the entry, “Interpretation of Quran Recitation through Movement”. Lastly, although interpretations of specific doctrines and principles within the religion have changed over time, I would argue that the foundation of religion, that of the perceived relationship between God and his followers has largely remained the same. God, who manifests himself in all living beings on earth, is still viewed as the ultimate source of light and guidance. The fundamental aspects of this relationship between man and God lie at the center of each blog post.

Despite these continuities throughout history, it would be an inaccurate representation of the religion to ignore the fact that as time progresses, an increasing number of interpretations of the religion can be found worldwide. Professor Asani refers to this phenomenon through the term, communities of interpretation, where each interpretation is shaped by the cultural, political, social, and economic forces of the region. It is this theme of diversity of interpretation that I discuss in my post, “Center versus Periphery Practices”. Holistically, I would like the reader of this blog to appreciate the ways in which Islam has maintained so many traditions and practices that are critical to its identity throughout the religion’s long history, while still making room for continuous evolution in interpretation.

The prevalence and importance of poetry throughout the history of Islam is an aspect of the course that I found particularly interesting and therefore placed a considerable emphasis on in my blog posts. In fact, his tradition of poetry in Arabia, the birthplace of Islam, outdates the religion itself. In pre-Islamic Arabia, poetry was the most cultivated art form and poets were admired and feared because they were believed to be connected with the spiritual world. Within the community, poets held the position of figureheads, filling the role of journalist, propaganda-maker, historian, and entertainer. At the outset, the original relationship between poetry and Islam was quite negative, with poets displaying extreme jealousy toward the Prophet because they saw him as their rival. Similar to poetry, the Qur’an is written in aesthetically beautiful verses that compel and move the listener. Poets even accused Muhammad of writing the Qur’an out of egotistical desire to gain recognition. Despite this initial tension, the poets ultimately supported Muhammad after taking the lead of acclaimed poet, Zuhayr. Since this early history, Islam has maintained an emphasis on religious expression through poetic verse.

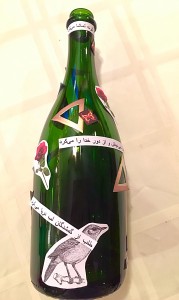

My blog posts feature several different works or genres of poetry, each of which engages closely with the religion. For example, Iqbal’s works, “Complaint” and “Answer”, discuss the reasons for the fall of Islamic power during the early 20th century and the influx of colonial forces. Iqbal conveys his argument through poetic verse. This work is discussed in the entry, “End of an Era”. The ghazal is a genre of love poetry that I analyze through my post, “Wine, Roses, and Nightingales, oh My!”. This genre expresses an all-consuming love of God through rich imagery and symbolism. The final genre of poetry that I pull from in my posts is the Mathnawi, or narrative epic, “Conference of the Birds”. This is an extended allegorical work of poetry that discusses the relationship between God and man. These poetic works are significant because they demonstrate the continual emphasis on poetry throughout Islam’s long history. Furthermore, these religious poems are utilized in order to convey important religious ideas and questions that are at the core of the faith.

Another aspect of Islam that is central to the religion’s identity is the emphasis it places on recitation. Oral performance of the Qur’an is of such importance because that is the mechanism through which the word of God was transferred to Muhammad. For this reason, the act of listening to the Qur’an allows for a more authentic experience with the word and God. In her entry, “The Sound of the Divine”, Kristina Nelson explains the relationship between reading and hearing the Qur’an. She writes, “The ears hear more than the eyes see in the written text, and it is only in the sound that the miracle is realized,” (Nelson 258). By this she means when simply reading the text, a component of the message’s beauty is forced to go unnoticed. Furthermore, the act of recitation allows for a more intimate experience between the performer and the text. The former must interpret the message for him or herself and must draw upon their emotional reaction in order to give their performance life through rhythm and intonation. It is not only the reciter who benefits from this mode of religious practice, however. Nelson writes, “Like all great art, recitation can be transforming, the participants touched and changed,” (Nelson 259). Here, Nelson indicates that the listeners, too, have a unique experience when they listen to a recitation of the Qur’an. They are able to appreciate the message in a more profound way than by simply reading, as the aesthetic beauty of the performance adds an intangible layer of meaning. While it is true that poetry is frequently recited, allowing this theme to tangentially relate to each of the poetic entries, the post, “Interpreting Qur’an Recitation through Movement”, engages most closely with understanding the importance of recitation, as I dance to a recording of the Qur’an. This allows me, the listener, to have my own interpretive experience as I listen to the recitation, which, in turn, is another individual’s interpretation of the text.

The final theme of continuity that I wish to put forth as a lense through which to analyze these blog posts is the perceived relationship between God and his followers. God has always been seen as a source of illumination and it is believed that he passed this illumination to each of his prophets, in turn, concluding with Muhammad. In his work, “Seven Doors”, Renard describes this relationship between God, mortal prophets, and followers, saying, “God has established, moreover, a history of revelatory communication embodied in a succession of prophets, beginning with Adam. Through that unbroken chain of spokespersons, God has continued his self-revelation through another sign, namely, that of the verses of the scriptures given to the principal prophetic intermediaries,” (Renard 2). This idea of illumination and guidance through scripture is one that has gone unchanged throughout history, as the breakdown of this belief would likely bring the integrity of the religion itself into question. More specifically, this relationship between God and prophets, which I discuss more in my entry, “Prophetic Light”, is one that has also held throughout time.

The relationship between God and man is shown to have a much more intimate aspect than is simply dictated through scripture and prophetic intermediaries, however. It is a widely-held and longstanding belief that God is present in all living beings and even maintains an exceptionally strong presence in nature. It is thought that revelation can be reached through both introspection, where one looks within himself to find God, as well as by observing nature and looking for ayat, or signs, of God within it. Renard elaborates on this idea when he says, “Muslims believe that God has, since the beginning of time, actively communicated with and through all of creation in a variety of ways. Foremost, God communicates in the very act of creating, by suffusing the universe with divine signs. More intimately, God communes with each animated being by infusing those same signs into every individual,” (Renard 2). These conceptions regarding the relationship between man and God are applicable to each work that the blog posts discuss. When reading the analyses, it is important to ask how this relationship manifests itself in the work and if there are any questions raised regarding the nature of that bond. If the work does raise such questions, consider how the post discusses or responds to those questions.

While considerable continuity can be seen throughout the religion, I would be remiss if I did not also highlight the ways in which the religion has diverged since its creation. In Islam, the two primary sources of guidance are the first and foremost, the Qur’an, followed by the examples set by the Prophet Muhammad. However, these two sources are not exhaustive, leaving considerable room for interpretation, which is necessary whenever one must determine how the principles of Islam fit into daily life and society as a whole. Furthermore, these interpretations are undoubtedly shaped by the world in which each group or individual finds himself. Thus, Asani suggests the cultural studies approach as a way to both analyze and appreciate the multitude of interpretations of the religion. Asani writes, “If we change our analytical lens from the poetic to the sociopolitical, we can consider the interplay between historical contexts and ideologies, such as colonialism and nationalism, in shaping contemporary expressions of Islam,” (Asani 16). By taking these historical and cultural factors into account when considering a given interpretation of the religion, a more meaningful appreciation and understanding can be gained than if one instead sets out to determine one “true Islam”. This increased appreciation is also discussed by Asani, when he emphasizes that, “In the course of historical evolution, such a dazzling variety of interpretations, rituals, and practices have come to be associated with the faith of Islam,” (Asani 12). Thus, an individual is only enriched by considering this more complex view of the faith that has developed through history.

In sum, this blog is meant to illustrate both the dynamic and enduring aspects of Islam. By doing so, it is possible to gain insight into the traditions and beliefs that lie at the core of the faith. Among these, I encourage readers to consider the intimate relationship between God and his followers, the importance of oral tradition and recitation, as well as the emphasis placed on individual interpretation throughout history. I hope the entries of this blog help to entertain these ideas and questions. Thanks for visiting!

Works Cited

Asani, Ali S. Infidel of Love: Exploring Muslim Understandings of Islam. Introduction-Chapter

- 2015.

Nelson, Kristina. Popular Expression of Religion: The Sound of the Divine in Daily Life.

Accessed Online.

Renard, John. 7 Doors. November 11, 2014. Accessed Online.