When approaching my portfolio of work, it may be useful to begin with my background as a student coming into this class. I, like most students at Harvard, was never well-versed in Islam, but perhaps unlike most students, I was also never well-versed in any religion. I was raised secular and most of my studies have been secular as well. As a result I’ve found it difficult to connect with the concept of religion on a spiritual level, and to me the weight that people placed on faith was always difficult to grasp. My course load so far has largely been heavy on the hard sciences, and I have never had much experience with religious or cultural studies. Though I have always disliked the mutually exclusive science/religion dichotomy that people try to foist on life, as a student studying evolutionary biology, I have sometimes found it difficult to reconcile scientific objectivity with religious thought. Come freshman year, though, I was placed with two roommates who were not only Muslim, but science concentrators as well. While not as orthodox as some, they followed many of the tenets of Islam that we ended up studying in this course. Our room was very open in terms of communication, but the subject of religion was rarely broached – not out of awkwardness or unwillingness, but simply out of incident.

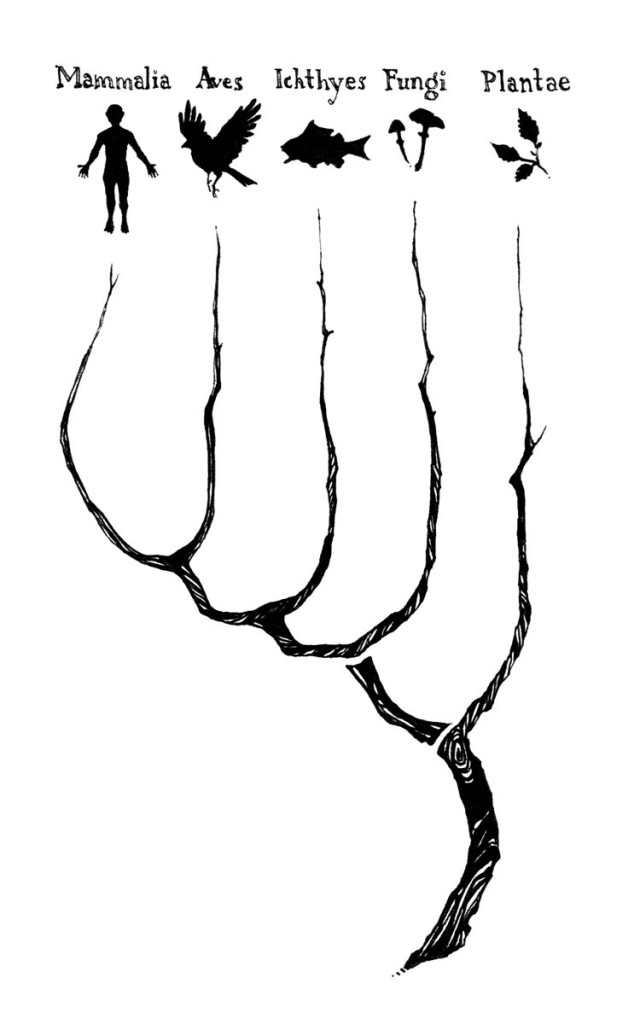

Still, my freshman year roommates were definitely a factor in my deciding to take this course. Throughout the semester, the boundary between science and religion was a focus of mine, and I tried to touch upon this with my blog entries (and it may be useful to note that, as the course progressed, the existence of this boundary became less and less distinct). For example, in my calligraphy piece, I tried to reconcile man’s origin story as told from the perspectives of Islam and of scientific fact. In several of my other pieces natural motifs carried through, especially those of animals, plants. etc.; these were unifying ideas not only from a biologist’s perspective, but from the perspective of Muslim art as well. From the nature symbolism in the arabesques in mosque murals to nature imagery in ghazals, it became readily apparent throughout the course that the natural world exerted great influence on Islamic art and architecture. I also tried to maintain a bold, graphic aesthetic throughout my blog posts, which is a carryover from my background as an illustrator. I have found that this form of illustration is often a clear way to synthesize and represent a literary piece.

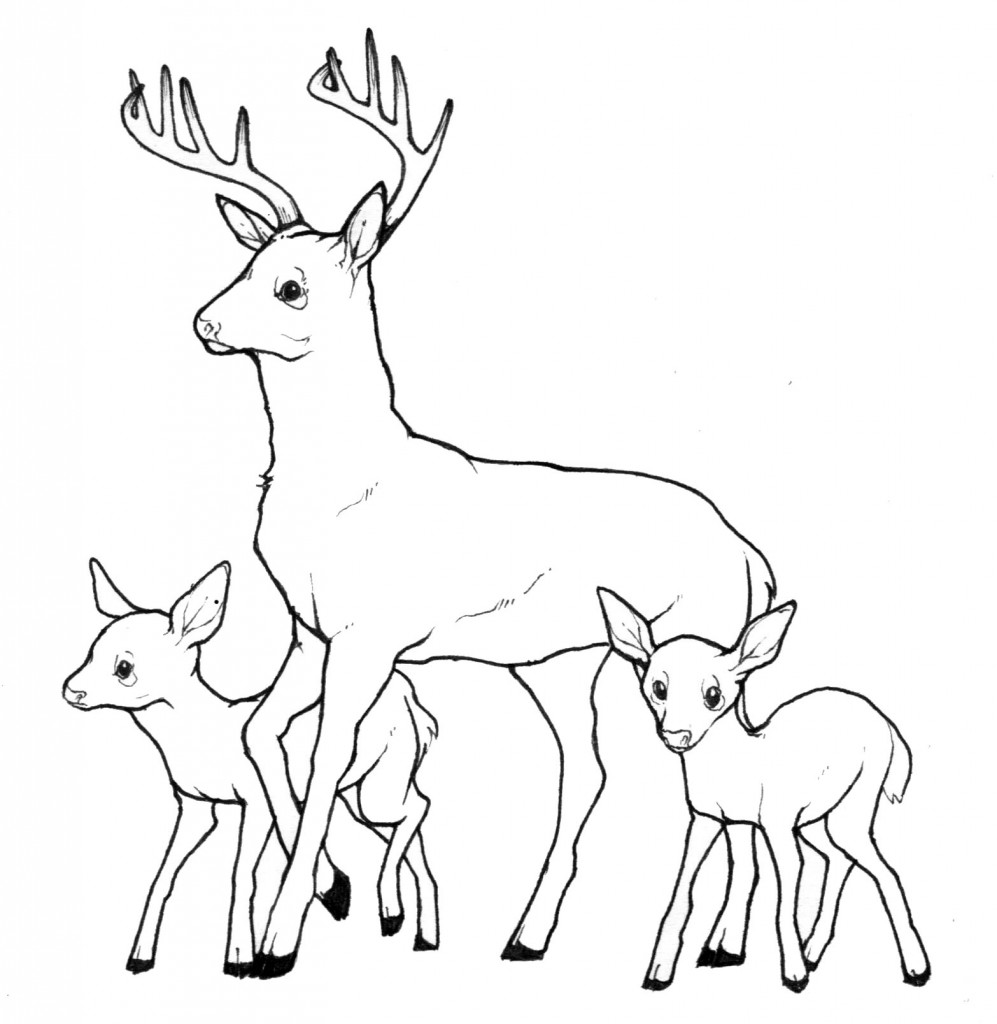

It was probably my biologist’s leanings that made the readings that involved animals and nature the most memorable to me, and consequently these were the stories I chose to illustrate in most of my entries. The parable with the deer in week four, for example, reminded me a great deal of a story in Buddhism. In the story of the moon rabbit, an old man begs several animals for food. The bear offers meat, the monkey nuts, and the otter fish, but the rabbit knows how to gather only grass, which the old man cannot eat. Instead he offers his own body to the man, sacrificing himself in the fire. But the old man reveals himself to be an incarnation of the Buddha and spares the rabbit’s life, inscribing his likeness in the moon in recognition of his selfless good deed. In the same way, in the parable of the deer, Muhammad honors the deer’s sacrifice by sparing her life. In some respects this story is even more striking in that it is not by a direct divine hand that the deer is spared; it is the hunter who, moved by the deer’s sacrifice and also by Muhammad’s trust and goodwill, ends up sparing the innocent deer. These stories that extend beyond the human realm end up resonating with me, perhaps because they show that God’s will extends beyond man and into animals, plants, and all things.

This same idea is reflected in my week one project. In class Prof. Asani told us a short story that really resonated with me, and which culminated in the idea that to a true Muslim, every leaf in a forest is a page of the Qur’an. This was also the week in which I learned that the Qur’an is interpreted as the literal word of God, not only as a transliteration like the Bible. It was a natural extension of this idea, then, that every object in the natural world would be adjacent to the Qur’an, as both were directly created by God. The notion that one could live one’s life reading every flower as an ayat, every bird’s call as a call to prayer, was incredibly moving to me.

In the same vein, I really enjoyed the week in which we read The Conference of the Birds. While a compelling story on its own, I think the fact that it was told from the perspective of some very colorful bird characters made it instantly charismatic and approachable. The graphical representation of thirty birds composing the silhouette of a great bird (Simorgh) leapt immediately to mind while reading the story, but I decided to represent the piece on an acetate projection to bring Islamic light symbolism into the piece as well. The use of light also serves as a metaphor of enlightenment and realization, such as the realization come upon by the birds in the story. This semester I also took a VES course in which we discussed methods by which one might fill a space. One option was to use light and shadow, with which one might turn a very small object into one capable of dominating a room. While reading The Conference of the Birds I thought this application might be relevant, as the story conveyed the idea that, with God, man is greater than himself; that is, larger than himself.

With this notion in mind, I began to reassess my “science vs. religion” approach to things. Science to me has always represented the route by which man would seek to extend himself beyond the literal. Concretely, we are just apes on a rock in space, but with science and the pursuit of knowledge we have carved out an existence that is so much more. It can be construed, perhaps, as a heuristic in which we find meaning through accomplishment. Islam, and perhaps religion in general, seeks to generate the same sort of meaning-beyond-reality. Again, seeing God in leaves or blades of grass and hearing God’s word in birdsong adds a whole new dimension to and beyond existence. From this notion on, science and religion seemed to suit each other more and more as complements rather than opposites. It became apparent that they would never become equivalent, but they became increasingly less at odds with one another. Science, for example, seemed largely concerned with the present and near future, focusing largely on improvements in technology and infrastructure and medicine. Religion, while also concerning the day-to-day, also places heavy emphasis on what comes after life. It may be somewhat contrived to say that one follows the strictures of religion in pursuit of a divine reward in heaven, but it is certainly not entirely untrue; for example, many of the ghazals and short stories we read spoke of the great divine reward that awaited the meek after death. Those who are poor, and downtrodden, and oppressed but who remain true, will be met with their just deserts.

On this note of marginalized groups, as a female, I was interested in exploring the attitudes towards women in Islam. Colloquially in the West, Islam is regarded as a religion that is not entirely empowering towards women. Accordingly, I found it surprising that so often in the course we spoke about how Islam was used as a vehicle to encourage women towards education and even towards science. I was especially engaged by the discussion of the veil and how the West was inclined to incorrectly read it as an entirely oppressive practice. Hyperbolically, these ideas were encapsulated in our reading of “Sultana’s Dream”. I found the reversal striking and somewhat ridiculous with the descriptions of pseudoscientific solar and water power, but the piece seemed to achieve its intended effect; if a world in which women are in complete power and men are shut away is ridiculous, why is the converse acceptable? I chose to illustrate the piece using the nature themes echoed in some of my other blog entries, pulling from a particular part of the story in which men are compared to wild animals. While this may be a largely hyperbolic comparison, I found it a useful and impactful visual device to illustrate.

While it facilitated a great deal of discussion, this course did not fully resolve all the tensions I felt existed between science and religion. One of these instances came to light in week two, in which we discussed the symbolic drinking of Qur’an in order to cure illness. Given the reaction of several Muslim members of the class, I gathered that this was not a widely known or acknowledged practice. Still, I found it rather disconcerting that there were people in the world that believed that drinking ink and paper would have any sort of curative power, and even that different pages of the Qur’an had different effects on the body. This idea fell too close to the notions of homeopathy and sham medicine that continue to be an issue today. Even taking into account the effect of a placebo if the drinker is devout, I have always been a firm believer that medicine should be just that: medicine. There are too many stories about Jehovah’s witnesses refusing life-saving blood transfusions, of patients with curable cancers dying because they prefer colloquial remedies, of children dying while their parents pray instead of seeking medical attention. Later in the course I was relieved to learn that in Islam, it is divinely imperative that one take care of one’s body, and of course Islamic countries have historically been far more advanced than their Western counterparts in terms of medicine. In this respect I made the practice of drinking the Qur’an a little ridiculous by tying in Alice in Wonderland, a fundamentally absurdist novel. I did not mean for it to be entirely farcical though, and the symbolism of ingesting the Qur’an outside of a medical perspective was not without merit. Without the medical context, I saw it as a sort of initiation into the world of Islamic study from the inside out.

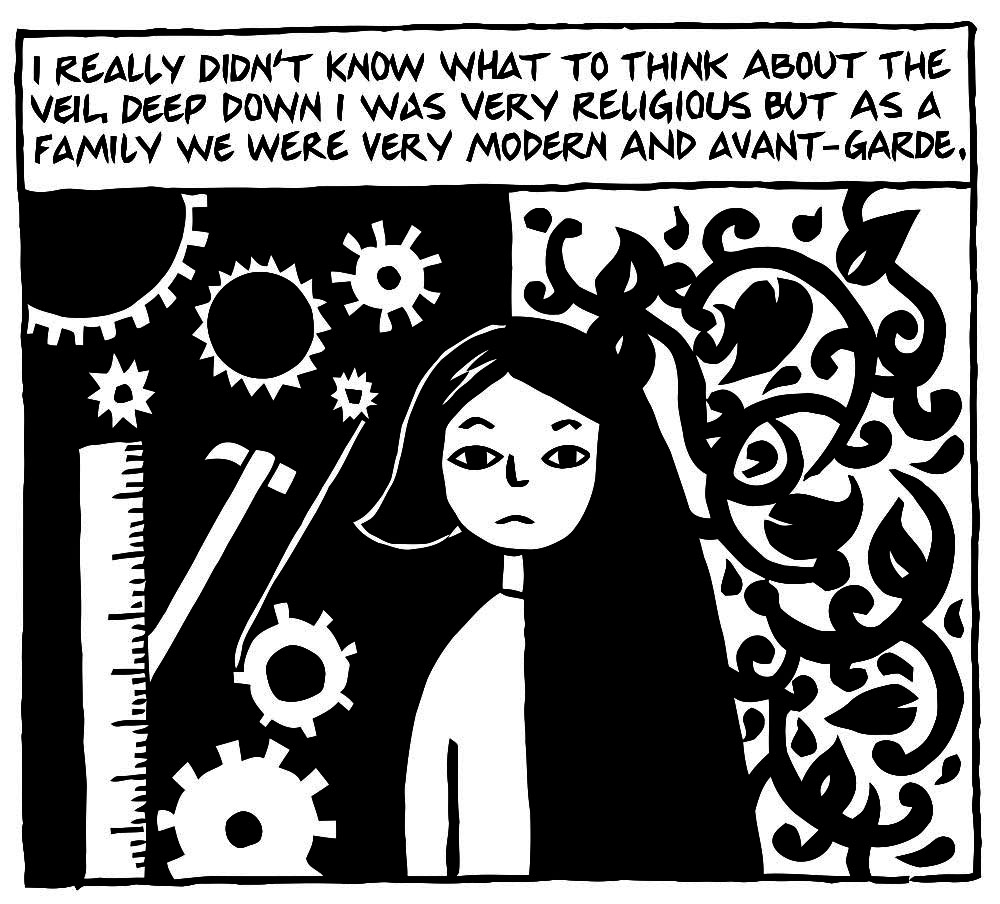

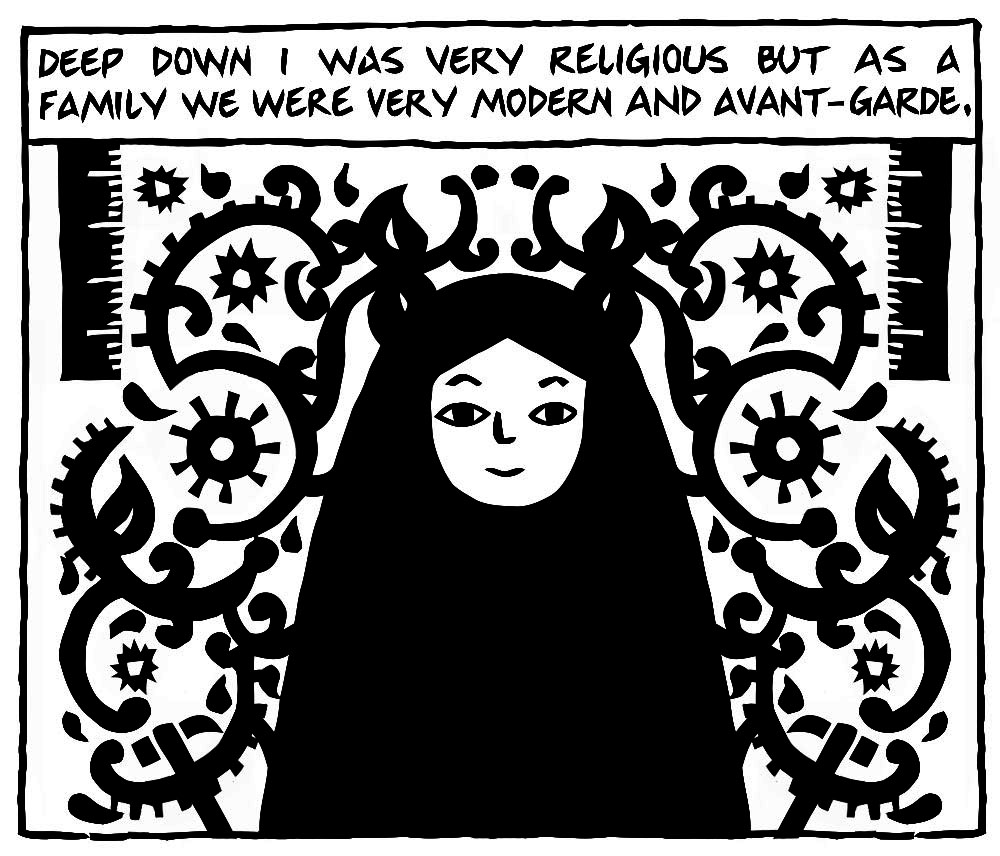

My exploration of Islam from the perspective of a scientist came to a head with our reading of Persepolis. Marjane seems to experience a similar internal struggle between a fundamental desire to be religious and close to God and the need for modernity. She goes through the same ideological turmoil concerning the veil and treatment of women and those who are lower-born. Her struggles are dramatic and literal: she harbors dreams of becoming a famous scientist until the universities are closed during the revolution. Her struggle between the religious and scientific sides of her is ultimately left out of balance, as she veers towards Western scientific thought towards the end of the novel. However, I figured that this need not always be the case, and for this reason I decided to alter the illustration of her internal struggle. After this course, it has become apparent to me that it is possible for all of these seemingly disparate elements – being female, wearing a veil, and studying science and technology – to exist in harmony. Her struggle closely paralleled my own as this course progressed.

In all, I found this course and especially the blog post aspect of this course to be very engaging. If nothing else I did learn a great deal about the realities of Islam, which were largely a black box to me and many others prior to enrolling. I have learned that for all its outward difference, Islam is a massively unifying and accepting faith and that it is largely due to media and misinterpretation that our gut feeling is, perhaps, Islamophobic. I have also immensely enjoyed my personal journey exploring Islam through the lens of a biologist and as an artist as well. I was surprised as to how personal the whole journey was, and how much what I learned in the course depended on what I brought to it. In this sense the blog assignment has largely been a reflection of what a blog is fundamentally intended to be; a document of one’s personal experiences and reflections thereof. As my first foray into a formal study of religion, A&I 54 has been a largely positive one, and I especially enjoyed approaching it from so many angles: both conceptually (through art, music, architecture, culture, literature, and faith) and from the perspective of so many students from so many backgrounds.