Intro Essay

Posted in Uncategorized on May 2nd, 2018Katie Okumu

Dr. Ali Asani

AE 54

2 May 2018

Introductory Essay

The most important thing I have learned in Aesthetic and Interpretive Reasoning 54 at Harvard University is how different Muslims around the world experience their faith from day-to-day. This course highlights and celebrates the cultural diversity of the Muslim world and showcases the artistic influences of sub-Saharan African and South and Southeast Asia. Dr. Ali Asani, the director of this course entitled For the Love of God and His Prophet is dedicated to fighting religious illiteracy by contextualizing and humanizing the narratives surrounding Islamic practice. This dedication in enacted by dispelling the most vocal narration of Islam that is so often co-opted by powerful figures for social and political gain. To dispel what Asani has coined “Loud Islam,” this course explores musical, artistic, and literary aspects of devotional life across multiple different themes and multiple different cultural contexts. This introductory essay seeks to outline the more profound components of the course that have left a marked impact on my understanding and appreciation of Islam. Secondly, this essay will provide a thematic structuring for the blog posts that conveys which conceptions of Islamic religious tradition and community I find particularly compelling and applicable to my creative projects.

In AE 54, I was particularly drawn in by the way that cultural, political, historical, and social contexts that influence artistic devotional expression of Islam. This is not to say that I, nor the structuring of this class critique and interpret Islam through the lens of Western modernity. In AE 54, one must be intentional to forfeit the critique of social and political norms simply because they differ from those accepted in the West. Instead, I thoroughly enjoyed being able to analyze and comprehend the implications for why different expressions of the faith exist. For example, during the third week of the course, we read The Sound of the Quran in Daily Life and discussed the social context that influences individuals to master recitation not only to access the power of God but to access capital and social wealth (national spotlight). I was fascinated by concepts of power, particularly concerning who has access to the Quran and the power it embodies. The historical background offered in class was beneficial. For example, the idea that after the standardization of the Quran, access to the work became more limited to elites and members of the state was a useful framework. The idea that aural encounters with the text were, and continue to be, most accessible, is an interesting construction that I believe falls in line with the question: What are the political and social structures that determine authority? Cultural context was explored in our discussion of what influences devotional expression in the Ta’ziyah, a theatrical expression of devotion wherein spectators are required to cry. Many prostrate to convey an appropriate reaction. In a cultural context, this is a rehearsed and disciplined way of accessing God through bodily engagement. The cultural context reads that actions devoid of intention and spiritual content are still valuable and can influence the actions of the soul. Grappling with these contexts in order to challenge my own preconceived ideas of how devotion should be articulated and why it should be articulated. These notions are influenced by the role of colonization and the history of Western, imperial expansion in the defamation of the figure of Muhammad in the early nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. I believe that the various calculated moves to defame the image of the Prophet in Asia and Africa are proof of the importance of the role of the Prophet in the belief in Islam and in the hearts of Muslim people. They are also proof of the importance of a class like Ali Asani’s where the narrative is reclaimed with focus reshifted.

There were specific thematic clusters explored throughout the course that I harkened back to in my creative posts that I found particularly engaging. I navigated my own understanding of the signs of God (those found in nature) and the 99 names of God, two concepts that we were introduced to early in the spring semester. My creative exploration of these two topics helped ground the more contextual artistic readings I did later. I became incredibly enraptured with the concept of the ghazal, a form of Persian poetry that invokes human context of love, marriage, romance, and even physical intimacy into devotion for Allah. The incorporation of this theme reflects an awareness of the influence of Sufism and the historical context of seventh-century Arabia. The drunkenness and erotic-like symbolism in ghazals are in direct conflict with rules about piety and sanctity, which I think are important in dispelling outside narratives about how one practices Islam. Finally, my creative projects explore the social contexts directly by examining the role of women in Islam through my creative projects. Overall, the cultural, political, historical, and social contexts that influence the artistic devotional expression of Islam are explored in my blog posts with a particular focus on the relationship between conceptions of the state and Islamic identity.

At this point of the essay, it is critical to delve into a more in-depth analysis of each individual creative blog post. This is important in order to showcase more intricately the traditions and diverse cultural components of Islam that each post highlighted to break down conceptions of the state. The analysis will not be in the order of completion. My first blog entitled Calling Allah ~ ‘Ismu ’l-’A‘ẓa, is a poem that invokes the different names of Allah. In AE 54, we explored the 99 names of Allah and the way they appear in artistic renderings of Allah’s power and glory during the introduction to the course. The title of the poem, ‘Ismu ’l-’A‘ẓam, translates to, “the most supreme and superior name.” Throughout the poem, I invoke the following names: Al-Alim, the all-knowing one, Al-Baseer, the all-seeing, Al-Khabeer, the all-aware one, As-Sami’, the All-hearer, Al-Ba’ath, the infuser of new life, Al-Muhaymin, the preserver of safety, Al-Haadi, the provider of guidance Al-Jaami’, the assembler of scattered creations, Al Muntaqim, the avenger, and Al-Adl, the embodiment of justice. The names of Allah are reflective of their attributes and are influenced by verses in the Qur’an. Recitation of these names is said to develop awareness of Allah and to allow Muslims to dwell on the plurality of Allah’s nature. Told from the point of few of a Rohingya Muslim, this poem explores the pain of being persecuted for one’s beliefs and physical attributes in a Buddhist-majority country. The invocation of the names of Allah is used to convey the emotional intensity of the Rohingya genocide in Myanmar and to explore the power of said invocation. The different names of Allah showcase the multiplicity of Allah’s relationship with people and the way that verbal invocation can showcase devotion. In the piece, I invoke 10 names of Allah to articulate details of suffering: the absence of state citizenship, accusations of violence, and physical torture. Individuals have been deported/faced years in prison for delivering Sufist teachings. The power of aural recitation is further emphasized by lines that refer to the silencing of voices and the context of the silencing of Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar. The visioning of this artistic expression as an avenue for the narrator to connect with Allah is indicative of the larger idea within AE 54 that artistic expression is a critical component of Islamic devotion and understanding. After reading this blog post, I would hope that the audience might comprehend the socio-political complexity of Muslim identity outside of the prominent narrative of Islam being practiced within Muslim majority countries. I would also hope that a comprehension of the multiplicity of Allah and the importance of invoking the name of Allah is found.

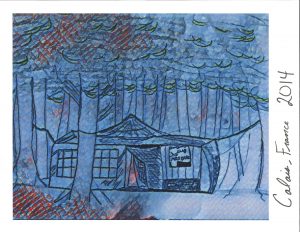

My second blog post was thematically similar, in that it navigated the individual experiences of Muslim refugees outside preconceived notions of the state. To challenge these notions, I created an image of a portable mosque that is similar to those utilized by Muslim refugees in Calais, France. I incorporated a different artistic style into my portfolio, utilizing coloring pencils, shading pens, and Adobe InDesign to create the final product. This creative project drew upon the art and architecture of mosque and other places of Muslim devotion we discussed in Week 6 of AE 54. My project was inspired by our discussion of the way temporal space helps mold and shape the world we live in was explored. For example, the way wooden minarets in Bosnia that incorporate both original Ottoman architecture with the resources of the region. I decided to depict a conception of a Mosque that incorporated traditional styles from the cultural context of where the refugees traveled from, while also incorporating the socio-political context of the individuals’ status as refugees. I also incorporated the future-oriented vision of Azra Aksamija to draw a Mosque that with aesthetic pieces and imagery that imagines the way Islam functions in the 21st century and might function in the future. This was important in the sense that it allowed us to note how aesthetic representations of Islam do not exist in a vacuum and are subject to variability. Most importantly, the audience is able to view a useful construction of Islam that is neither a-historical nor a regional but also is not engaging in a strict temporality.

The creative project that centers my portfolio was the most difficult to complete. Entitled, If You Educate a Woman, You Educate a Nation. The piece of prose engages with the relationship between gender identity and Islam. The piece follows my train of thought after viewing the documentary Koran by Heart and hearing the father of one young competitor repeat the words that became the title to his daughter who he would not allow to attend secular secondary school. I was immediately struck by the weight of that responsibility being placed on the shoulders of a young girl, and most women who practice Islam. In class, we explored the way that nation-states used women’s bodies to express national/political ideologies. Specific examples of western nations using their rescue of persecuted women to justify colonialism and during The Iranian Revolution. The continuation of women in the 21st century being utilized as entities to criticize Islam was the final piece of inspiration for my project. In the piece, I take on the role of a mother who has learned in her own way to teach her daughter how to take up the self-agency she herself lacks. The prose seeks to critique the way religion has been conceptualized as nationhood, and the way that women are being utilized as a way to both bolster, protect, and take advantage of nations. This prose also critiques the way religious roles of women and men have been translated to become political roles and societal roles from the outside perspective and, in the case of Koran by Heart, from the inside. In this way, my prose seeks to show the audience critiques of the relationship between religion and the state while also analyzing social and political contexts that help shape understandings (in this case my own) of Islam.

The next two creative blog posts that I utilize in my portfolio are ghazals. Not far removed from the last blog post, I am drawn to the ghazal because gender is not part of Persian language within the ghazal, meaning that the poetry form is more inclusive of women and those who do not identify as men. In Persian devotional poetry (the ghazal), the main theme is love: there is a search beyond the perception of rational meaning. The narrator represents the loved, God is the lover, and wine tends to act as a symbol of love. Becoming wine drunk and intoxicated acts as a metaphor for becoming overwhelmed by the love of God. In this way, the ghazal is a powerful tool is showcasing an interpretation of Islam that is focused on love as opposed to violence or hatred as conceived by some actors in the West. This interpretation shifts focus away from Islam as a physical or bordered “state” and towards the conception of a “state of mind.” Love is seen as something that will complete a person and make them whole, just as God does. Satisfaction is something that is not regarded in a negative light but showcased as being attained when convening with God. The two gazals, entitled Needing God and What Are The Words are quite different in style. Needing God speaks directly to a monotheistic figure, while What are The Words employs the classic style of utilizing romance and physical desire to replicate devotion and adoration for God.

The final blog post is entitled Ayat, which means “sign of God.” The ayat are quite varied but are often described as that which are present in nature itself. We explored this concept in the first few weeks of class, in order to explore the way the Quran guides human kind towards a more full and more appropriate comprehension of these signs. I utilize construction paper, pens, and scissors to create a 3-D flower. Each petal on the flower is adorned with an image of a sign of God’s love and power: the sun, trees, the mountains, and the Quran itself. The signs of God operating to form a flower showcase, in my mind, the detail that goes into the reflection spoken of in the verse. On one particular petal, a human eye represents a sign of God. I felt the inclusion of humanity as a sign of God to be quite important, as it is not only what the eye beholds that is significant of God’s power, but the gift of the eye that my gaze upon the greatness of God. Although this blog post does not deal directly with conceptions of the nation, I believe the focus of this blog post on the way faith and devotion are reflected in everyday life and creation showcase the breadth of Islam and the way that it is not confined to borders of the nation.

For the Love of God and His Prophet is a course of a lifetime. It brings together music, art, and performance to showcase Harvard students to different conceptions of faith and living life truly. I am forever indebted to the course for allowing me to explore my own conceptions and preconceptions of the Islamic devotional life, and convey to others the complexity of context that Islam sits within. Grabbing hold of this understanding allows one to become more aware this world’s potential, and, hopefully, their own.