The Public Domain January 8, 2008

Posted by keito in : Licenses , comments closedAn increasing number of contributions made on the Internet today are released into the public domain. Basically this means that the author disowns any copyright on the material, allowing it to be copied, modified, and redistributed for any purpose (including commercial purposes) without the author’s permission.

Once a work is released into the public domain, it is essentially out there for anybody to use for whatever purpose – there’s no need to get permission, follow attribution guidelines, or pay royalties. The flip side is that the original author no longer has any rights over the released work – even if the work is resold and ends up making a fortune, for example, the original author can receive no recourse for it.

What, then, is the appeal of the public domain that results in so many people releasing works into the public domain in recent years? Part of the reason is similar to the reason why free licenses are so popular today: licenses are becoming increasingly more visible on the Internet, and furthermore, organizations such as the Creative Commons and the Free Software Foundation have devised ways in which licensing becomes no longer an issue exclusively for law professionals but for the average Internet user too.

What is the legal backing behind releasing works into the public domain? Basically, the public domain constitutes anything that isn’t copyrighted: works in this category include formerly copyrighted works that have passed their copyright expiration date (which depends entirely on the country), works that were created before copyright was created, and works that were never in copyright (certain government-created materials, and materials that the creator released into the public domain). It depends on country to country whether releasing one’s work into the public domain is actually codified or not. In many countries, including the United States, releasing works into the public domain itself is not codified, and is instead treated as an abandonment of property (since copyright is automatically assigned under the Berne Convention) under common law.

Public domain is basically the most radical copyleft license there is; the author reserves no right to it the licensed work, and licensees are free to do whatever they wish with the work, whether that involves plain copying, modification, or redistribution, for profit or otherwise. The number of Internet users subscribing to a copyleft approach as radical as this is still very low. This is completely logical, as users will feel less well compensated by a public domain work than, say, a work licensed under the only slightly less radical Creative Commons Attribution license.

Because of this, I do not feel that there is any specific need to press for authors to release their works into the public domain. It is far more important to encourage more individuals, and more organizations and companies, to use a license that offers real freedoms (as do the Creative Commons licenses), but still offer the copyright owner some protection.

Free software licenses January 7, 2008

Posted by keito in : Licenses , comments closedOf course, Wikipedia articles, blog entries, and photos aren’t the only thing that can be freely licensed. What really kicked off the free license movement was the introduction of free software licenses. The most famous may be the GNU General Public License (GPL), which is the license under which a large portion of the Linux operating system is available.

Created and maintained by Richard Stallman and the Free Software Foundation, the same organization that maintains the GFDL, the GPL allows licensees to freely distribute copies and modifications provided a number of requirements are followed. One major restriction is that any derivatives or verbatim copies must be licensed under the GPL too (the GPL has a viral clause, similar in spirit to the GFDL). This means that companies cannot take free software, make a few modifications to it, and then re-release it as proprietary software. Another restriction is related to patents. The GPL forbids licensees from putting patents on GPL-licensed software, citing the fact that “any free program is threatened constantly by software patents.”

The last restriction, which is perhaps the most important, is that all licensees of the software must be given access to the source code. Licensees must either receive the source code along with the compiled version of the software, be able to request it and receive it from the developers for at least three years, or be given an Internet link where they can download the code (perhaps the most oft-used approach).

What’s interesting is the way in which the GPL makes itself enforceable. Because users of free software do not sign licenses (and often are not even given the opportunity to click the click-wrap “I agree” buttons that are common in proprietary software), it is very plausible for a user to say that they did not see the license when they started using the software. The GPL notes this, saying, “You are not required to accept this License, since you have not signed it.” (§ 5) However, it goes on to note “nothing else grants you permission to modify or distribute the Program” and that any modifications or redistribution imply that the licensee has read and accepted the license.

This is interesting in that it notes two layers of rights: the default layer, which is restricted by law, disallowing any modification or redistribution of the software, and the GPL layer, the one with many of those restrictions waived. The GPL layer comes into existence only when the licensee has read and accepted the license; therefore, if anybody claims not to have read the GPL but engages in any redistribution or modification that would have been allowed under the GPL, they would simply be breaking the copyright laws present in the default layer.

The GPL is not the only popular free software license. Many others exist, including the MIT License. The MIT License, developed at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, is even “freer” than the GPL: it allows licensees to create derivatives and license them in any way, including for profit.

The choice of whether to use the GPL, or an even freer license, such as the MIT license, is not one to be taken lightly: if the developer creates a product licensed under the MIT license, and later decides to reuse some portion of the code in a commercial product, he or she risks having competitors who have the same code and who can also resell their derivatives if they want. With the GPL, this is avoided – all licensed copies cannot be sold for profit, but the developer still has the right to use the code in any way he or she wants.

That is the beauty of free software licenses: while giving users and other developers new freedoms that were unheard of back when proprietary software was the only paradigm, they still manage to protect developers and their right to be compensated for their hard work. Many developers see the beauty in this, and decide to license their software under a free license, bringing us today to a world in which almost anything – from enterprise-level database software to the core software that powers our phones – is available gratis.

Photo Sharing and Creative Commons January 6, 2008

Posted by keito in : Licenses, Websites , comments closedCountless websites have sprung up that allow users to upload their photos and other artwork to a website where they may be viewed by visitors from around the world. Some of these sites, including Wikimedia Commons (a media repository for Wikipedia and its sister projects) and Flickr (a popular photo sharing site), allow users to license their uploads under one of several free licenses; others, such as Facebook (surprisingly or not, one of the most popular websites for photo sharing in the United States), have taken a dimmer approach to free licensing.

Photos are no different from texts in that they have an automatic copyright; however, I think they’re also different in that very good photographs can often be sold for a price (unlike, say, a contribution to a blog or an article on Wikipedia). This means that photographers are sometimes reluctant to give away rights to their photos as easily as their text contributions.

Despite this, however, there are a huge number of images on Flickr and the Wikimedia Commons that are licensed under lenient free licenses. In the case of the Wikimedia Commons, a free license is required — all media that are not licensed under the Creative Commons, GFDL, or a similar free license are deleted. Still, it’s amazing that so many people have licensed their photos and other artistic creations under free licenses that may even allow others sell their work for profit.

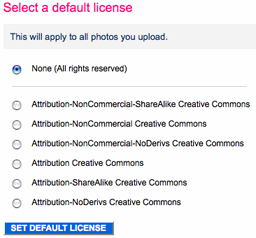

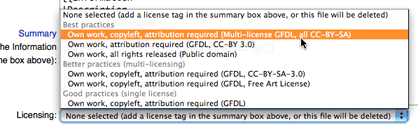

Part of the reason, I think, is the relative ease-of-use of the licenses, as I mentioned in a prior post. But some of it is thanks to these websites, who have made it incredibly easy for users to license their contributions under a free license. Users uploading images to the Wikimedia Commons are presented with a selection box that allows them to select a license of their choice; on Flickr, while the default license is “All rights reserved” (i.e., no free license at all), it is a matter of a few clicks to go into the preferences screen and change the default license for all past and/or future uploads.

Flickr default license selection screen:

Wikimedia Commons upload interface with license selection:

Compared to the relative “automaticness” of Wikipedia’s GFDL licensing, both of these websites make the user explicitly choose to license their media under a free license. Even then, freely licensed media are available in abundance — all this can only mean that the free licensing movement has caught on among the regular Internet crowd, even among those who would not have been interested in licenses before.

All of this is not without its downsides, though. There will always be companies that take such freely licensed media from the Internet (much of which is of sufficient quality to be used in professional settings) and use it for their own profit. While this is explicitly allowed under the free licenses that many of these media are licensed under, it has and will most definitely continue to generate controversy when it happens.

One particular example is of Virgin Mobile and Flickr. In 2007, Virgin Mobile used several freely licensed (specifically, CC-BY licensed) images from Flickr in their advertising campaign. Virgin duly attributed the images, printing in fine text the URLs of the Flickr profiles of the original photographers. So far, so good. The problem was with one of their posters that used a freely licensed image with a picture of a girl, Alison Chang, in it.

The problem ultimately was that although Flickr had every right to use the photo itself in their advertising campaign (as they had attributed it), they did not have the right to use Chang’s likeness in their campaign without a model release. Even worse, the poster’s tagline, “Dump Your Pen Friend,” is clearly derogatory and insulting to Chang.

In the end, Chang and the photographer sued Virgin Mobile, and surprisingly, the Creative Commons organization because “as the creator of [the CC-BY license], they have an obligation to define it succinctly.” It will be interesting to see what happens with this lawsuit. While it seems that Virgin Mobile appears to have committed some privacy violations (wholly unrelated to copyright), the plight of Creative Commons seems to be less easy to predict. I would guess that Creative Commons has no obligation to specify each and everything that licensees may do with CC-licensed content. Considering that CC is a free license that deals with copyright issues, those using the licenses should consider other issues, such as privacy and using the likeness of people, in parallel with copyright. Creative Commons should not be held liable for organizations and other entities that fail to do their due diligence in this regard.