Navy T-28 Engine Failure: Life lessons linger 40 years after

ø

Scattershooting while wondering how quickly 40 years can pass…

“One of the finest displays of cool professional airmanship under pressure…”

— Vice Admiral W.L. McDonald.

When I was young, I always wanted to fly and to be a fighter pilot. That urge to fly was suppressed until I was accepted for Navy flight training in 1981. I interrupted my academic studies to attend and graduate from Aviation Officer Candidate School (AOCS, Class 2381) at NAS Pensacola with academic distinction. I received a Presidential commission to serve as a line officer in the U.S. Navy on September 11, 1981.

In addition to an array of leadership and soldering skills acquired at multiple DOD schools, serving as an officer and naval aviator also helped reinforce and refocus my early training in physics into practical applications related to aerospace engineering and its foundational fields of structural, mechanical, electrical, and computer engineering.

After commissioning, I attended primary flight school at NAS Corpus Christi, and then advanced jet fighter/strike school at NAS Kingsville, Texas. In flight school, I was named to the Commodore’s List for “academic and flight excellence.”

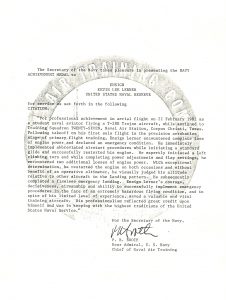

While still a student naval aviator, I was awarded the Navy Achievement Medal after managing an engine failure on takeoff and returning the field for a dead stick landing.

It was literally a life-defining moment.

In primary flight training at NAS Corpus Christi, I flew an old WWII style T-28. The T-28 was a massively overpowered trainer (especially compared to more contemporary military training aircraft) that offered steep learning curve to generations to new Navy flight students. On the road to flying a Tomcat, it was a necessary but difficult plane to master. I volunteered to fly it because I wanted the challenge and because the only squadron (VT-27) still flying the plane was located in Texas.

On just my second solo flight (PA2) – a flight to practice basic aerobatic maneuvers like loops, wingovers, and aileron rolls — I had a complete engine at 700 feet as I attempted to stay below landing pattern altitude until I could clear the base and climb out over the Laguna Madre. When the engine died, I immediately put the plane into optimal glide configuration and turned away from the base toward the water. As I tried to restart the engine, I also prepared to ditch the plane.

While flashbacks of Dilbert Dunker training during AOCS flashed in my brain, I went through emergency NATOPS restart procedures. Nothing worked until, at 200 feet, I tried the one shortcut procedure discussed by my instructors not in the NATOPS flight manual . By holding prime button, I dumped raw fuel into the carburetor and the engine caught. Holding the button, I continued to climb as turned back toward the base toward at a point called ”low key” where I could thereafter shoot a power off dead stick emergency landing.

This tale also includes my student-like slavish devotion to procedures that forced me to take my finger off the fuel prime button in order to key my microphone to make emergency radio calls (an action resulted in two additional power failures on my way back the base), a broken altimeter, and being shot at with a flare gun by the Runway Duty Officer (RDO) while I held off dropping the landing gear so that I could glide to the field.

This tale would, however, be incomplete without some humor at my expense. I had obviously not yet mastered a seasoned fighter pilot’s “Yeagerisms” and demeanor, and so the control tower tapes of the accident revealed an increasingly higher-pitched urgency in my voice during those aforementioned radio calls that became fodder for subsequent squadron ready room fun. It was many months before I regained a reputation for steely Yeager-esque resolve during night O-nav flights (attack training flights at high speed and low radar-avoiding altitudes (e.g., 200 to 500 feet AGL ) using structures and visual landmarks for navigation). I learned there were few things more satisfying that simply saying “Roger that” when asked to do outrageous things with a plane.

More seriously, however, what I learned of lasting value was command presence, and need to not to show fear or urgency even in crisis. I learned that — especially in times of chaos and crisis — keeping a quiet presence calms other, and that a quiet mind enhances problem solving.

For “professional achievement in aerial flight,” I was awarded the Navy Achievement Medal (see below) for “courage, decisiveness, and airmanship,”

Far better than the medal, however, was a short communiqué from Vice Admiral W.L. McDonald to my squadron commander. Admiral McDonald graduated in the Naval Academy class with Wally Schirra (one of the Mercury 7 original astronauts. Flying an A-4, he led the first air strike against North Vietnam following the Gulf of Tonkin incident.

McDonald wrote that my handling of the affair was “one of the finest displays of cool professional airmanship under pressure that I have had the pleasure to observe.”

Admiral McDonald would go on to serve as commander of Operation Urgent Fury.

A copy of Admiral McDonald’s communiqué remains one of my prized possessions.

The there is still, however, a more humor to be milked from this incident.

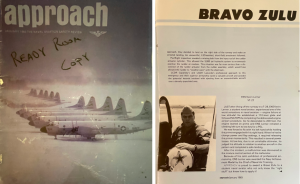

I was also given a “Bravo Zulu” in the January 1983 issue of Approach, the Navy flight magazine.

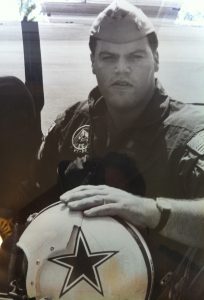

Months passed, however, between the time I raced from jet training at NAS Kingsville back to NAS Corpus Christi to have my photo taken in a T-28 cockpit and the time the photo appeared in print. The delay was a result of the Navy photo lab having to airbrush a sleeve on my bare left arm.

This was, remember, long before photoshop and I had originally posed for my photo with my sleeves rolled up. This was very fighter pilot-esque, but not pleasing to the Navy Safety Office. 😉

The photo gaffe became emblematic of two personal maxims I hold dear:

(1) If you want to lead a life devoted to a general disdain of rules and guidelines — and even occasionally indulge in flagrant violation of said rules and guidelines (especially as an operational necessity) — one must perform at a high level when the chips are down in times of real crisis, and

(2) it is usually better to ask for forgiveness than permission.

I still love to fly. Whenever possible, especially at outlying fields, I use the military 180 “numbers for the break ” and still practice a carrier approach pattern for landing. I love practicing emergency landings, and I will do aerobatic maneuvers whenever allowed by the type plane I am flying. I invested years in preparing to fly a vintage WWII Spitfire in England, and I love taking young naval flight students for introductory rides to share a bit of language and “attention to detail” culture.