In 2008, I interviewed author, inventor, and futurist Ray Kurzweil for Computerworld. The focus of the published interview (no longer online, sadly) were some of the more startling concepts in his book The Singularity Is Near. But there were a few other bits and pieces that were just as interesting to me, including his thoughts about long-term document storage.

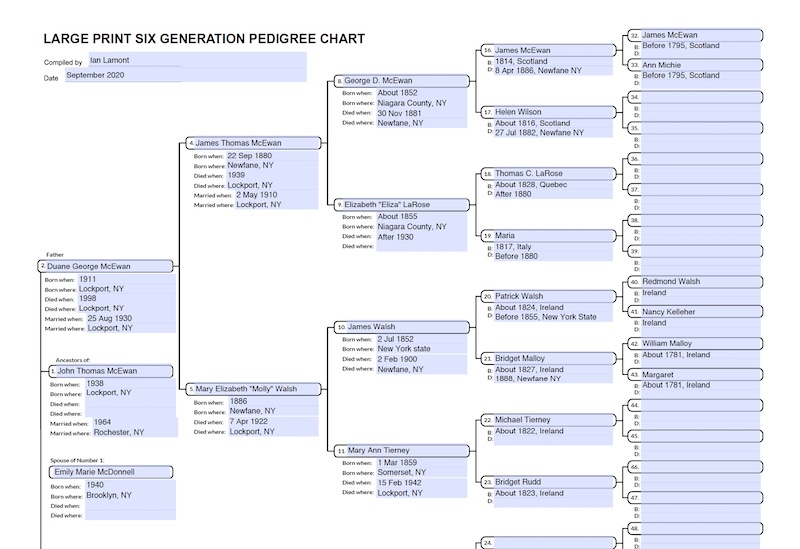

In my mind, I’ve gone back to that interview several times in the past 13 years, mulling over the implications for innovation in my own genealogy business, which sells paper genealogy charts and forms as well as genealogy PDFs. I decided to dig it out the transcript and share an excerpt below, and give some follow-up commentary about the implications for long-term document storage for genealogists.

Ian Lamont: In the Singularity is near, you also discussed an intriguing invention, which you called the “Document Image and Storage Invention”, or DAISI for short. But you concluded that it really wouldn’t work out. Could you talk a little bit about that?

Ray Kurzweil: That’s interesting. I don’t usually get asked about that, because it doesn’t seem like that interesting an issue.

Ian: It’s interesting to me, because I think I fall into the same category as your father, someone who likes to save all the documents and things related to their lives. I’d buy it!

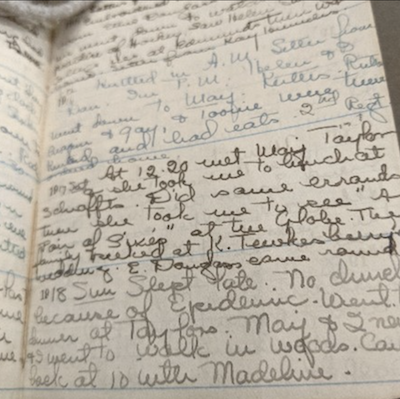

Ray: Well, we have the same inclination, I inherited that from my father, and I inherited 50 boxes of his documents which was all his letters and so on. And I’ve kept … I have several hundred boxes of documents, and now of course I have a lot more stuff electronically, which is also not very well organized.

The big challenge, which I think is actually important almost philosophical challenge — it might sound like a dull issue, like how do you format a database, so you can retrieve information, that sounds pretty technical. The real key issue is that software formats are constantly changing.

People say, “well, gee, if we could backup our brains,” and I talk about how that will be feasible some decades from now. Then the digital version of you could be immortal, but software doesn’t live forever, in fact it doesn’t live very long at all if you don’t care about it if you don’t continually update it to new formats.

Try going back 20 years to some old formats, some old programming language. Try resuscitating some information on some PDP1 magnetic tapes. I mean even if you could get the hardware to work, the software formats are completely alien and [using] a different operating system and nobody is there to support these formats anymore. And that continues. There is this continual change in how that information is formatted.

I think this is actually fundamentally a philosophical issue. I don’t think there’s any technical solution to it. Information actually will die if you don’t continually update it. Which means, it will die if you don’t care about it.

That’s true of our own lives. People don’t care about themselves, don’t in fact survive very long. We have to continually maintain ourselves as biological entities, when we can make that transition to nonbiological, we’ll still have that same issue.

Ian: You said there’s no technological solution. What about creating standards that would be maintained by the community, or would be widespread enough that future …

Ray: Well, that helps for awhile. We do use standard formats, and the standard formats are continually changed, and the formats are not always backwards compatible. It’s a nice goal, but it actually doesn’t work.

I have in fact electronic information that in fact goes back through many different computer systems. Some of it now I cannot access. In theory I could, or with enough effort, find people to decipher it, but it’s not readily accessible. The more backwards you go, the more of a challenge it becomes.

And despite the goal of maintaining standards, or maintaining forward compatibility, or backwards compatibility, it doesn’t really work out that way. Maybe we will improve that. Hard documents are actually the easiest to access. Fairly crude technologies like microfilm or microfiche which basically has documents are very easy to access.

So ironically, the most primitive formats are the ones that are easiest.

So something like Acrobat documents, which are basically trying to preserve a flat document, is actually a pretty good format, and is likely to last a pretty long time. But I am not confident that these standards will remain.

I think the philosophical implication is that we have to really care about knowledge. If we care about knowledge it will be preserved. And this is true knowledge in general, because knowledge is not just information. Because each generation is preserving the knowledge it cares about and of course a lot of that knowledge is preserved from earlier times, but we have to sort of re-synthesize it and re-understand it, and appreciate it anew.

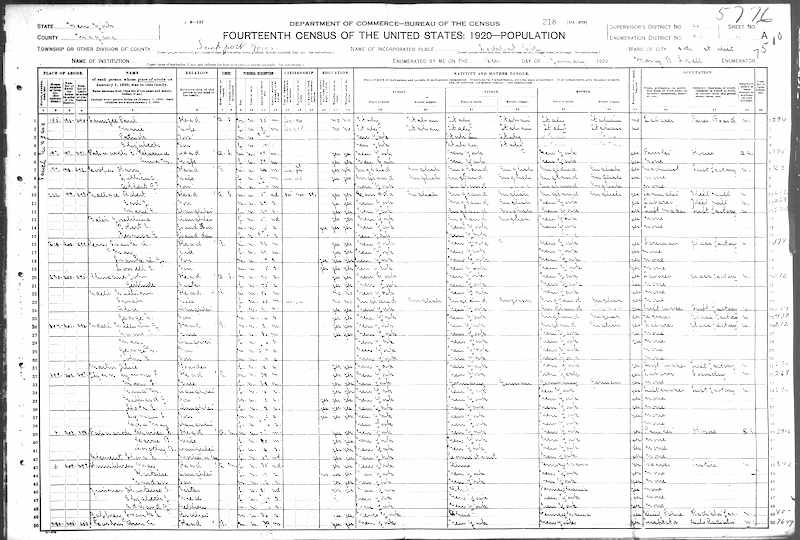

As a genealogist, I have thought a lot about solutions to preserve data for the long term that don’t have physical limitations of microfiche or paper media, or the problem of computers crashing, subscriptions lapsing, or for-profit online services shutting down (see “Ancestry deleted 10 years of my family’s history“)

Maybe 10-15 years ago, a few people in the Silicon Valley futurist community came up with the idea of a ball or disc etched with gradually smaller text an excerpt from the Old Testament, translated into multiple languages. It was actually called the “Rosetta Disc.” The plan to seed the discs across the world so even if there was some great calamity or the loss of written languages, future civilizations could resurrect them. Here’s what the disc looked like:

Here’s how the concept was described:

The Rosetta Disk is the physical companion of the Rosetta Digital Language Archive, and a prototype of one facet of The Long Now Foundation’s 10,000-Year Library. The Rosetta Disk is intended to be a durable archive of human languages, as well as an aesthetic object that suggests a journey of the imagination across culture and history. We have attempted to create a unique physical artifact which evokes the great diversity of human experience as well as the incredible variety of symbolic systems we have constructed to understand and communicate that experience.

The Disk surface shown here, meant to be a guide to the contents, is etched with a central image of the earth and a message written in eight major world languages: “Languages of the World: This is an archive of over 1,500 human languages assembled in the year 02008 C.E. Magnify 1,000 times to find over 13,000 pages of language documentation.” The text begins at eye-readable scale and spirals down to nano-scale. This tapered ring of languages is intended to maximize the number of people that will be able to read something immediately upon picking up the Disk, as well as implying the directions for using it—‘get a magnifier and there is more.’

On the reverse side of the disk from the globe graphic are over 13,000 microetched pages of language documentation. Since each page is a physical rather than digital image, there is no platform or format dependency. Reading the Disk requires only optical magnification. Each page is .019 inches, or half a millimeter, across. This is about equal in width to 5 human hairs, and can be read with a 650X microscope (individual pages are clearly visible with 100X magnification).

The 13,000 pages in the collection contain documentation on over 1500 languages gathered from archives around the world. For each language we have several categories of data—descriptions of the speech community, maps of their location(s), and information on writing systems and literacy. We also collect grammatical information including descriptions of the sounds of the language, how words and larger linguistic structures like sentences are formed, a basic vocabulary list (known as a “Swadesh List”), and whenever possible, texts. Many of our texts are transcribed oral narratives. Others are translations such as the beginning chapters of the Book of Genesis or the UN Declaration of Human Rights. …

I looked into the details of this project, and wondered if it could be applied to genealogy. I was also thinking about the ancestor tablets found in many home shrines in Taiwan, long-lasting physical manifestations of a person’s lineage which are brought into people’s religious beliefs and ceremonial practices.

However, whether it’s stone, wood, or high-tech micro-etchings, there are practical limitations of applying this idea to genealogy or any written record, including cost and the inability to update the text. For instance, a separate project, NanoRosetta, is a fantastic application of microetching digital images on nickel to create a permanent archive, but it can’t be updated and requires a fair amount of file preparation (PDF and TIFF) that not everyone is capable of doing.

It made me think that a more realistic solution to the genealogy preservation problem aligns with Kurzweil’s “most primitive” take: Preserve core records on paper, share them widely with relatives and cousins, and use an easy-to-understand versioning system. This could also be applied to other family records, including letters, manuscripts, and more.

We know high quality paper can last hundreds of years. It can be easily copied and spread, potentially allowing the information to last thousands of years, as evidenced by Roman, Greek, and early Chinese dynastic records and literature that can still be read today.