Yesterday, I participated in a live video discussion about my Lean Media book. One of the topics that came up was the relationship of the Lean Media framework to Lean Startup, a business and product framework first articulated by Eric Ries nearly ten years ago. He ended up releasing a book titled Lean Startup, and the concepts outlined in it are now widely followed by tech startups and business units at larger companies. (Eric expands on how some of these innovative concepts can be applied to larger ventures and multinational corporations in his new book The Startup Way).

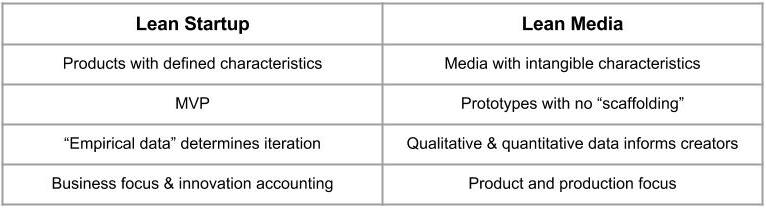

I’ve acknowledged Lean Media’s connections with Lean Startup since I first proposed the Lean Media framework right here on this blog five years ago, but it’s worth exploring in greater detail how they differ. To some, the two iterative product development frameworks may seem similar, but there are some profound differences, too.

The following chart lays it all out:

In the first row, Lean Startup addresses products with defined characteristics – a light bulb or SaaS application. In certain cases there may be design elements, such as a smartphone case or pair of shoes, but at the end of the day such products also serve practical purposes, such as protecting your phone or your feet. They therefore have practical value and can be assigned a price. They can also be designed and produced in a methodical fashion, building out components and features to reach the desired specification. Lean Startup’s build-measure-learn cycle brings in customer feedback to improve development of products with defined characteristics.

In the first row, Lean Startup addresses products with defined characteristics – a light bulb or SaaS application. In certain cases there may be design elements, such as a smartphone case or pair of shoes, but at the end of the day such products also serve practical purposes, such as protecting your phone or your feet. They therefore have practical value and can be assigned a price. They can also be designed and produced in a methodical fashion, building out components and features to reach the desired specification. Lean Startup’s build-measure-learn cycle brings in customer feedback to improve development of products with defined characteristics.

Media products, on the other hand, are designed to entertain and inform. In certain cases they may have knowledge value (e.g., a subscription to the Financial Times informs business people about issues that impact their careers) but in most cases they bring no tangible value. Media is all about intangibles — the hard-to-articulate qualities of work that elicit feelings and emotions in the people who experience them. Despite media’s lack of practical value, audiences are willing to spend one of their most valuable resources — time — to consume them. They may also spend a great deal of money on media experiences.

MVP vs. Media Prototype

The MVP (minimum viable product) is perhaps the most famous element of Lean Startup. The concept has also been debated, as I discussed on this blog in 2013 (see MDP: Minimum Delightful Product) and I have heard elsewhere. Ideally, it’s a functional product that can be shown to early adopters in order to test hypotheses and get feedback, but some founders expand the definition to include incomplete models or design prototypes, and often end up showing them to people who are not early adopters, such as journalists or prospective investors. MVPs are by definition not finished products, but early customers (or observers, investors, etc.) may have a hard time seeing past the flaws.

Lean Media does not use the term MVP. We already have lots of terms for early versions of a work — draft, rough cut, demo version, etc. — but in the book I group them all under the term prototype for all media formats. While early prototypes may be simple or incomplete, I instruct creators to be sure to remove from the media prototypes what I call scaffolding before showing them to test audiences. Scaffolding could include editors’ marks, time codes, and annotations that will distract from the work.

In the third row, Lean Startup relies on empirical data and validated learning to test hypotheses. An MVP might provoke some discussions with early adopters, but in the build-measure-learn cycle you need to be measuring what you are doing so you can make an informed, data-driven decision. For instance, will customers prefer a recessed headlight in the new car, or something that’s more flush with the front of the vehicle? Have your design team whip up some graphic renderings in their CAD programs, and then show them to prospective customers and measure which one gets more votes. It’s the classic A/B test.

For media, quantitative data can deliver insights as test audiences experience a prototype, but qualitative data explains why people feel the way they do about a media work being developed. Sometimes the quantitative indicators (20 “thumbs down” vs 10 “thumbs up” after reviewing a draft manuscript of a novel) may be invalidated by the qualitative feedback (75% of thumbs down concerned minor issues relating to chapter titles and the index, as opposed to fundamental issues with the story itself).

Regardless of the type of feedback, it’s intended to inform creators about the work, rather than dictating how they must proceed. This is a big difference with Lean Startup, which practically requires founders to follow where the empirical data takes them, even if it’s far outside their original hypotheses about what customers want.

Finally, Lean Startup is not just a framework for product development, it’s a framework for startup business development. For instance, in Lean Startup, Ries describes innovation accounting as a way for the company to reach its business goals. Lean Media has no such intentions — the framework is purely about product. While a media work that resounds with audiences can be the basis for a successful media venture, I do not explicitly address how to make a media business profitable. That may very well be the focus of my next media book (working title: Niche Media). Stay tuned!