Introductory Essay

ø

The Many Faces of Islam

Islam is often viewed in the west as a monolithic faith with one set of universal ideologies, beliefs, and values. Within our class we studied the many different understandings of the Islamic faith and what it means to be a Muslim within diverse social and geographic environments and in different historical periods. This was accomplished through the cultural studies method that approaches religion not as a specific doctrine, or monolithic set of sacred writings, but as a complex and changing human organism. Professor Asani noted in his book, Infidel of Love: Exploring Muslim Understanding of Islam, the unique advantage of using the cultural studies method to study religion, “It maintains that religions are shaped by a complex web of factors, including political ideologies, socioeconomic conditions, societal attitudes to gender, educational status, literary and artistic traditions, historical and geographical situation – all of which are inextricably linked in influencing the frameworks within which sacred texts, rituals, and practices are interpreted” (Asani, pg. 10). By understanding the differences within Islam we can better overcome ignorance and promote a greater understanding of the faith in many different contexts.

In our class the arts become the central vehicle to understanding the multiple expressions of the Islamic faith. Through our own artistic creations, inspired by class readings and experiencing Islamic art, film, music, dance, poetry, architecture, and literature, we were able to find a way to connect and engage with the world of Islam and begin to understand the unifying elements of Islamic art as well as the vast differences, often due to the absorption within Islam of ideas from the preexisting societies, cultures, and religions. As the weeks went by my artwork and blogs started to fall into four different categories: new responses to ancient Islamic art works; responses to current Islamic art works; interpretations of Islamic ideologies and thoughts; and reactions and artistic expressions to ongoing arguments and discussions within the Islamic faith. Through using the contextual or cultural studies method to examine the Islamic faith, I was able to draw upon a vast array of Islamic sources and art works to create an understanding of Islam that was multidimensional and rich in it’s diversity of thoughts and understandings. Professor Asani discussed the benefits of the cultural studies approach in his book, “A contextual approach to the study of Islam recognizes that the experiences and expression of any religion are far from homogeneous or monolithic. In the course of historical evolution, such a dazzling variety of interpretations, rituals, and practices have come to be associated with the faith of Islam that many Muslims, most of whose understanding of their religion are restricted to their specific devotional and sectarian contexts (Sunni, Shi’i, etc.) are astonished when they become aware of this diversity” (Asani, 13).

One of the major themes discussed within class was the paramount importance of the Qur’an for Muslims. My first poem and blog during week two dealt with the frustration that I was having in trying to understand the Qur’an without understanding Arabic. I felt that it was necessary to be able to understand the Qur’an as it is the heart and center of the faith for all Muslims. The sacred nature of the Qur’an, that being the revealed word of God to Muhammad, was difficult for me to grasp. I later realized that this was because I was looking at the Qur’an through a purely textural lens. While I was not able to understand the Arabic, I was still able to feel the beauty of the Qur’an through the taped recitations and through reading, albeit somewhat imperfect, translations. During the third week I created a collage that reflected the beauty of Qur’anic recitation that was viewed during the movie, Koran by heart, my reactions to listening to Qur’anic recitations on the website, and from examining the many examples of the refined art of calligraphy of the Qur’an. At this point I felt that I was finally entering into a ‘lived’ understanding of Islam. The great importance and centrality of the arts within the Islamic faith and the use of art as an expression of love of the Prophet were noted by Professor Asani, “…many Muslims have embraced the arts and literature as vehicles to express their idea about their religion. Thus poems, short stories, novels, folk songs, hip hop, miniature painting, calligraphies, films, architecture, and gardens offer us glimpses into Muslim worldview” (Asani, pg 21). The centrality of the arts in defining Islam is expressed in radically different ways throughout the Islamic world.

Another major class theme was the understanding of the different groups and interpretations within the Islamic faith. Followers of the Islamic faith are often viewed as one homogenous group following the same understanding and traditions. The vastness of the Islamic world often surprises people who tend to associate it mainly as a religion of the Middle East. By learning about the different interpretations of Islam, and particularly the differences that are found within the Sunni and Shi’ite communities, a greater understanding of continued conflicts among Muslims was gained. The succession of leadership after the death of Muhammad in 632 C.E. had ramifications that are as prominent and meaningful today as they were at that time. Muslims have different teachings regarding the early leadership of the Muslim community upon the death of the Prophet. Shi’ite’s believe that Ali, as the son-in-law and cousin and direct descendent of the Prophet, was designated to lead the Muslim community and that he and his descendants would become the future imams. David Buchman, in his article Shi’ite Islam in Contemporary Iran, discussed the special place of the imams within the Twelver Shi’ite community and the political ramifications of Shi’ite rituals in Iran, “…these rituals are still carried out by Iranians today, and some of them have been manipulated by clerics for political ends” (Buchman, pg. 78). The events at Karbala, whereupon Husayn, the son of Ali, and other members of his family were massacred in 680 C.E., created a permanent division between members of the Muslim community that was based upon the legitimacy of succession. My third blog and art project created a public garden and theatre for the unique Taziyeh ritual, particularly as it is performed within Iran today. From reading The Miracle Play of Hasan and Husein and reading about the Taziyeh ritual in Peter Chelkowski’s article, Taziyeh: Ritual and Drama in Iran, and most importantly, from viewing film footage of the ritual the deep emotional attachment and lived religious experience of the audience and ritual performers was strongly experienced. While all Muslims follow the teachings of the Qur’an and the Hadith of the Prophet Muhammad, the Shi’ites also follow the teachings of the Imams. Within Iran the annual Taziyeh ritual, reenacts the martyrdom of Husayn, the son of Ali, and hence takes on a political as well as religious importance. David Buchman discussed the modern implications and multiple meanings of the Taziyeh ritual in his article Shi’ite Islam in Contemporary Iran: From Islamic Revolution to Moderating Reform, and suggested, “Acknowledging this event means recognizing that although an injustice was done to Husayn, it was a necessary evil to allow purification of humanity’s sins. On a more spiritual level, to remember what happened on the plain of Karbala is to be reminded of the personal injustice all Muslims do to themselves and each other by not following the teachings of the Qur’an, the hadith, and the Imams” (Buchman, pg. 78). The emotional reaction of Twelver Shi’ite Muslims as they watch or participate in the reenacting of the Taziyeh ritual continually stresses and reinforces the different beliefs between the followers of Twelver Shi’ism and other Muslims.

Sufism was another major theme discussed in the course. Undoubtedly the reading that touched me the most was Farid Attar’s, Conference of the Birds. Learning about the esoteric tradition of Sufism and the deep piety and seeing it’s reflection in Sufi poetry, reading Persian poets Rumi and Hafiz, creating my own Ghazal, and ultimately creating a musical interpretation of The Conference of the Birds, opened my eyes to the vast beauty and mystical spirituality of the poetry of Islam and the continued importance of it today. Annemarie Schimmel noted in Mystical Dimensions of Islam that the Prophet stated in Hadith #535, “If ye had trust in God, as ye ought He would feed you even as He feeds the birds” (Schimmel, pg. 118). The symbolism within and seen throughout Sufi poetry and literature would have been completely missed without some understanding of Sufi mysticism. In the Introduction to Conference of the Birds, Dick Davis offers an understanding of Sufi beliefs, “The doctrine is elusive, but certain tenets emerge as common to most accounts. These briefly, are: only God truly exists – all other things are an emanation of Him, or are His ‘shadow’; religion is useful mainly as a way to reaching a truth beyond the teachings of particular religions, – however, some faiths are more useful than others, and Islam, is the most useful; man’s distinctions between good and evil have no meaning for God, who knows only Unity; the soul is trapped within the cage of the body but can, by looking inward, recognize its essential affinity with God; the awakened soul, guided by God’s grace, can progress along a Way which leads to annihilation in God” (Davis in Attar, pg. XII). The moral teachings, wisdom, and guidance within Conference of the Birds are relevant for people of any religious background and at any time in history. Reinforcing the reading was seeing a visual representation in a miniature painting from Iran created in 1600 C.E. by the artist Habiballah at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The painting was a page from the manuscript of The Language of the Birds, and was created by painting in ink, watercolor, gold, and silver on paper. The beauty of that work perfectly captured the delicacy and questioning nature of the narrative. Within my musical composition I attempted to create music that touched upon the questioning nature of Sufi spirituality, but reinterpreted this Islamic art form within the understanding of a person who was not a Muslim living within the 21st century and trained in jazz music. This modern response to a Persian Islamic literary art form created in 1175 C.E. emphasizes the ongoing relevance of Islamic artistic works.

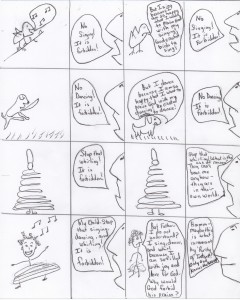

The debate over music and dance being forbidden or prohibited within some divisions of Islamic society continues to this day and some of the most interesting readings and discussions in our class took place around the different reactions to music throughout the Islamic world. Anne K. Rasmussen discussed the different reactions to music and recitation in The Qur’an in Indonesian Daily Life; The Public Project of Musical Oratory, “In spite of various historic controversies surrounding the inappropriate use of music, something Nelson refers to as the “Sama Polemic,” there seems to be an understanding in some parts of the Arab world about the reciprocity between good singing and good recitation” (Rasmussen, pg. 36). Rasmussen continued to talk about the difference in music performances in the Arab world as opposed to Indonesia and suggest that the performer-audience dynamics are not a part of Indonesian life, “In Jakarta, concerts of Arab music (haflat) where audience members, overpowered by the performance of a great singer, swoon, sway, dance, and call out exclamations of enthusiastic approval and self-indulgent participation, are rare. Great Arab performers do not tour Indonesia, and the aesthetics of kayf, saltanah, and tarab, all Arab terms having to do with the enchanting power of music to drive one to ecstasy, do not seem to be part of Indonesian musical and aesthetic discourse. Indonesian music, including the many kinds of Islamic popular and folk music, and the demeanor of Indonesian audiences are very different from those found in the Arab world, and it is perhaps for this reason that the comparison of recitation with music is simply not the issue of grandeur that it might be in an Arab context” (Rasmussen, pg. 36). While dance is prohibited within many parts of the Islamic world the Turkish Mevlevi Whirling Dervishes use dance to reach a transcendent state of rapture. The many different Islamic responses to music and dance led me to create my blog and graphic comic during week eight that dealt with this debate and questions that I found confusing regarding the prohibition of music and dance.

The place of women and gender within the Islamic world was another central theme discussed within class. My final blog and artwork revolved around the complex issue of purdah. Within the Islamic world the place of women in society is vast and varied. With the resurgence of Islam and a return to Shari’ah law rather than secular law in countries such as Saudi Arabia and Iran the role of women is once again in great flux, reflecting both a modern industrialized society and traditional roles set forth in the Hadith. Muslim women are also re-examining the Qur’an and the Hadith and searching for new interpretations of their place within Muslim society. The use of the headscarf as a marker of Islamic pride by some women was particularly interesting as many people from the west view it as a symbol of oppression.

Through the use of the cultural studies method to examine Islam it became clear that the Islamic faith varies as much as each individual person varies from the next person. There is not one Islamic faith but many different Muslims – each with their own lived experience of the faith. Through examining the arts, as a reflection and glorification of the love Muslims have for God and the prophet Muhammad, it is possible to get a glimpse into the vast diversity of ideas and inspirations that are a part of the world of Islam. One piece of art and one ideology does not define all Muslims. Through understanding the diversity of ideologies and thought within the Muslim world throughout history, and by studying the magnificence of Islamic artistic achievements, a deep respect, admiration, and understanding is inevitable.