By Eric Priest in Beijing

This week Google and its partner Top100.cn launched a China-only ad-supported DRM-free music service that could serve as a proof of concept for other such services around the world. A lot of people will be watching this service closely to see if it can successfully monetize music on the internet in the world’s toughest piracy market.

As my friend Maths has pointed out in his initial review of the service, this service is aimed directly at stealing market share from China’s leading search engine, Baidu, which gets a big percentage of its traffic from its comprehensive and extremely controversial free MP3 search and download feature. After poking around on the new Google service for a little while, I can say that this service has a long way to go before it threatens Baidu. But clearly the folks at Google-Top100 know that. This is a long-term play for Google.

A few other quick impressions.

1. Google is lying low. This was a pretty soft launch. The hype has been muted, and there seems to be little marketing of the site right now. In fact, on the main Google.cn page there are no promos, images, ads, or even links to a music site. The only way I found it was—based on a tip from a friend—typing “google.cn/music” in my browser URL field. This seems to be a very early experiment, and Google/Top100.cn know they’re low on content so they’re really just taking it for a test drive at this point. Which brings me to point no. 2…

2. The content offering is pretty modest. It’s impressive that the site features content from several of the international majors as well as big regional labels like Rock Records. (In my initial poking around I’ve found tracks from SonyBMG, Universal, and EMI on the site, but nothing from Warner, though a friend who should be in the know has told me Top100 has cut deals with all four majors). However, there are significant limitations: there appear to be Chinese artists only—no international artists—and not all tracks are available for download (some are streaming-only). Some major Chinese artists are not available at all. (Incidentally, for those not familiar with the Chinese music market, each of the four major labels has a large stable of Chinese artists, so that’s why it’s the case that the majors are participating yet there are no international artists available.) I expect this limited content catalog, though, is only temporary. Top100.cn is no doubt working out lots of new licensing deals to build up the catalog considerably in the coming months. It appears though that the major labels are also in a wait-and-see mode here, as even their Chinese catalogs are far from fully represented, and in a number of cases the major Chinese artists on the site have just a small handful of songs available on the service.

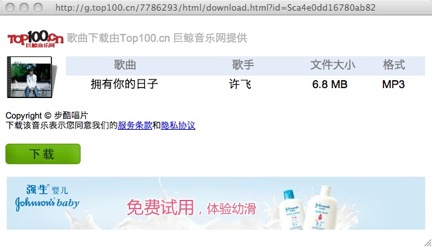

3. The interface is (unsurprisingly) clean and Google-esque. The backend is powered by Top100.cn, but it’s clear that Google drives the front-end design. It’s clean, simple, no-frills. It’s somewhat less cluttered than Baidu’s main music page. In China, of course, this could be a strike against Google’s design as many Chinese tend to like their web pages “renao”! The music homepage consists simply of a list of the top 100 new songs on the service. Clicking on an artist’s name from either the search results page or the music homepage brings up an artist page with bio, and album pages that link from the artist page. Clicking on a song pops up a simple in-browser Top100 streaming player. The player has a scrolling lyric function, which is pretty much a must nowadays for online music services in China. For songs in which downloads are permitted, clicking on the download link pops up a separate download window. And that seems to be about it. But that’s probably enough in this market if the quality of service is good and content offering is rich.

4. MP3s! The service does not permit downloading of every song; some songs are available for streaming only. Those that you can download are in 192kbps MP3 format. That’s big news because this is the first instance in the world in which the major labels are permitting free, ad-supported MP3 downloads. That’s, no doubt, why they are not licensing international artists to Google at the moment; clearly the majors are worried about leakage outside of China, but aren’t too worried about leakage of local Chinese content, since Chinese artists have a very limited market outside Mainland China, HK, and Taiwan. Nevertheless, the downloads are supposedly limited to Mainland Chinese users.

5. Advertising is basic and unobtrusive. There are no ads on the google.cn/music homepage, on any of the artist or album pages, or the search results page. Banner ads appear at the bottom of the pop-up Top100 player and download windows. Additionally, there are no audio ads wrapping the songs, as I had thought might be the case, the way We7 embeds short radio-style ads at the start of each song.

6. Labels view this as a branding opportunity. So long as they are willing to license their content to this service, labels are clearly hoping to use it to build up a little brand recognition while they’re at it. The relevant record label logos are prominently featured when music is playing in the pop-up player.

So, where is this headed? Any service in China that tries to do things the “right way” by rustling up licensing agreements first before making music available is at a huge, often fatal, disadvantage. It’s just too hard to compete with ubiquitous free music. But Google and Top100 surely know that. That’s why they are not beating the drums loudly about this service now. They’re not looking to change the world with this today. This is a low-key, long-term initiative. But if they do it right, it doubtless has more potential than Baidu’s free, unlicensed music search model, which in my view is simply unsustainable in the long run. That said, the biggest question mark plaguing the Google/Top100 service is whether as an ad-supported service it can ever generate enough money to be lucrative enough to attract and retain good content. If it can, it could pave the way for such models elsewhere.