Afghan Hezbollah? Be careful what you wish for

Oct 10th, 2009 by MESH

From Matthew Levitt

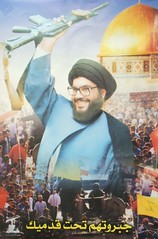

The Washington Post reports that some in the administration see the Lebanese Hezbollah as a possible model for transformation of the Taliban. Describing the Taliban as a movement “deeply rooted” in Afghanistan, much like Hezbollah is in Lebanon, proponents of a Hezbollah model for the Taliban see a scenario in which the Taliban participates in Afghan politics, occasionally flexes its military muscles to benefit its political positions at home, but does not directly threat the United States even if it remains a source of regional instability.

The Washington Post reports that some in the administration see the Lebanese Hezbollah as a possible model for transformation of the Taliban. Describing the Taliban as a movement “deeply rooted” in Afghanistan, much like Hezbollah is in Lebanon, proponents of a Hezbollah model for the Taliban see a scenario in which the Taliban participates in Afghan politics, occasionally flexes its military muscles to benefit its political positions at home, but does not directly threat the United States even if it remains a source of regional instability.

According to the Post, while the idea has been discussed informally “outside the Situation Room meetings,” it has not yet been presented to President Obama. That’s a good thing because the notion is deeply flawed, and its implementation would have dire consequences for Afghanistan, the region more broadly, and U.S. counterterrorism efforts all.

Hezbollah in Lebanon is a destabilizing force, as is the Taliban in Afghanistan. Not only does Hezbollah maintain an independent militia in explicit violation of United Nations resolutions, it uses this private army to create semi-independent enclaves throughout the south of Lebanon and the Bekaa Valley where Lebanese Armed Forces are not allowed. In these spaces, Hezbollah maintains training camps, engages in weapons smuggling and drug trafficking, and maintains tens of thousands of rockets aimed at its neighbor to the south, Israel. Hezbollah collects intelligence on people traveling through Beirut international airport, and has built its own communications infrastructure beyond the reach of the national government.

In Afghanistan, an independent Taliban militia that controls territory of its own; maintains bases and training camps; facilitates weapons smuggling; and engages in every aspect of the narcotics production pipeline from poppy cultivation and processing to taxing delivery and smuggling abroad, would certainly seek to maintain its control over its own territory. Indeed, an increasing number of major Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) arrests over the past few months have targeted drug kingpins closely tied to the Taliban, like Haji Juma Kahn and Baz Mohammad.

Neither will Hezbollah today nor a similarly modeled Taliban tomorrow tolerate government challenges to its private army or other sources of power. In the words of then-Principal Deputy Director of National Intelligence Donald Kerr, such groups are out for themselves, and will turn on their fellow Lebanese or Afghan citizens, respectively, when under pressure. “Events in Lebanon since May 7 [2008] demonstrate that Hezbollah—with the full support of Syria and Iran—will in fact turn its weapons against the Lebanese people for political purposes,” Kerr explained. “Hezbollah sought to justify its attacks against fellow Lebanese as an attempt to defend the resistance against attacks by the government.” Scores of Afghan civilians have been killed in Taliban suicide bombings, including the most recent attack outside the Indian embassy which claimed the lives of 17 Afghans, including 15 civilians and two Afghan police officers. It is all the more difficult to imagine a scenario in which the Taliban play a stabilizing political role in Afghanistan in light of the fact that, unlike Hezbollah, the Taliban adhere to a strict salafi-jihadi doctrine which is anathema to secular politics and requires the strict implementation of shariah law.

Commenting on the philosophical distinctions some in the administration make between the Taliban and Al Qaeda, White House press secretary Robert Gibbs distinguished between the Taliban as an Islamist element in Afghanistan and “an entity that, through a global, transnational jihadist network, would seek to strike the U.S. homeland,” like Al Qaeda. But in the assessment of people like Bruce Reidel, an Al Qaeda and Taliban expert who oversaw the administration’s policy review regarding Afghanistan and Pakistan, the Taliban’s ties to Al Qaeda run deep. “It’s a fundamental misreading of the nature of these organizations to think they are anything other than partners,” said Reidel. “Al Qaeda is embedded in the Taliban insurgency, and it’s highly unlikely that you’re going to be able to separate them.”

Here too, Hezbollah—a group involved not only in politics in Lebanon but in terrorist activity worldwide—is the wrong model. Even as the Hezbollah-led March 8 coalition campaigned ahead of Lebanon’s June 7 elections this summer, the group was forced to contend with the unexpected exposure of its covert terrorist activities both at home and abroad. At home, Hezbollah stands accused of playing a role in the assassination of former Lebanese Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri. Abroad, law enforcement officials have taken action against Hezbollah support networks operating across the globe, including in Egypt, Yemen, Sierra Leone, Cote d’Ivoire, Azerbaijan, Belgium, and Colombia. Just this past week, a court in Azerbaijan found two Hezbollah operatives guilty of plotting attacks on the Israeli and U.S. embassies in Baku, among other plots, and sentenced them each to 15 years in prison.

The Taliban is primarily involved in attacks in Afghanistan and Pakistan, though it has been tied to at least one plot in the United States and another in Europe. In the United States, a group of eleven jihadists in Northern Virginia were found to have connections with Al Qaeda, the Taliban, and Lashkar-i-Taiba. In Europe, the Pakistani Taliban—distinct from but closely allied with the Afghan Taliban—claimed responsibility for a failed plot to bomb subway trains in Barcelona in 2008. And while historically the Taliban was an adversary of Iran’s, the United States believes since at least 2006 Iran has arranged frequent shipments of small arms, RPGs, explosives and other weapons to the Taliban. The Qods Force also provides the Taliban in Afghanistan with weapons, funding, logistics and military training, according to the U.S. government.

As National Counterterrorism Center director Michael Leiter made clear in his congressional testimony last week, Hezbollah is a very poor model for a future Taliban. According to Leiter, the U.S. intelligence community holds the following to be true:

While not aligned with al-Qa’ida, we assess that Lebanese Hizballah remains capable of conducting terrorist attacks on U.S. and Western interests, particularly in the Middle East. It continues to train and sponsor terrorist groups in Iraq that threaten the lives of U.S. and Coalition forces, and supports Palestinian terrorist groups’ efforts to attack Israel and jeopardize the Middle East Peace Process. Although its primary focus is Israel, the group holds the United States responsible for Israeli policies in the region and would likely consider attacks on U.S. interests, to include the Homeland, if it perceived a direct threat from the United States to itself or Iran. Hizballah’s Secretary General, in justifying the group’s use of violence against fellow Lebanese citizens last year, characterized any threat to Hizballah’s armed status and its independent communications network as redlines.

Modeling the Taliban after Hezbollah is a recipe for failure. It would doom efforts to promote democracy in Afghanistan and engender long-term instability in both Afghanistan and Pakistan along the traditional Pashtun tribal belt that straddles the country’s shared border. It would embolden one of Iran’s newer allies in the region and empower a salafi-jihadi organization with close and ongoing ties to Al Qaeda to firmly establish control over parts of the country from which it would continue to produce massive quantities of drugs that ultimately make their way to the West. Looking to Hezbollah as the model for a future Taliban displays both ignorance of Hezbollah and naïveté regarding the Taliban. No matter how you slice it, that’s a dangerous combination.

MESH Admin: There is an Arabic translation of this post.

Comments are limited to MESH members and invitees.

2 Responses to “Afghan Hezbollah? Be careful what you wish for”

Posts+Comments

Posts+Comments Posts+Comments

Posts+Comments Posts+Comments

Posts+Comments Posts+Comments

Posts+Comments

Matthew Levitt has provided a realistic assessment in rejecting Hezbollah as a positive model for the Taliban, because it would exacerbate conflict rather serve as the steadying effect desired by the West. And he has provided us with a lead in his reference to social base of the Taliban, “the traditional Pashtun tribal belt that straddles the country’s shared border.”

Perhaps we should consider whether the Pashtun tribes are a problem because they are Taliban, or whether the Taliban is a problem because of its support by Pashtun tribes. Correspondingly, rather than considering how we should deal with the Taliban, perhaps we should consider how we should deal with the Pashtun tribes.

The American military has had recent success in allying with once-insurgent Sunni tribes in Anbar province of Iraq, and other tribes elsewhere in Iraq. They did this, in part, by dealing directly with the tribes, rather than through the framework of the Iraqi government. There is a good reason that such direct ties were successful: tribes are by their nature not units of states, but alternatives to states; tribes detest interference, and strongly prefer independence to state control.

As long as the intervention in Afghanistan places state-building as its highest priority, tribes will naturally lean toward resistance. So what is more important: building a state apparatus, or stabilizing the region and removing threats to external parties? In the short- and medium-run, treating with the tribes may be the most effective way to stabilize and neutralize the region.

Philip Carl Salzman is a member of MESH.

It might be useful to pinpoint the intellectual sources of the inaccurate analogy between Hezbollah and the Taliban. While we cannot say for sure, the views attributed to “White House advisers” in the Washington Post report sound familiar. Similar views have been expressed by the White House counterterrorism adviser, John Brennan.

In a 2008 essay entitled “The Conundrum of Iran: Strengthening Moderates without Acquiescing to Belligerence,” Brennan wrote the following regarding Hezbollah:

More recently, Brennan briefly made headlines for essentially reiterating this argument at a talk he gave at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in early August. Brennan’s comments came in response to a question by The Nation correspondent, Robert Dreyfuss, whether the United States should start talking to organizations like Hamas, Hezbollah and the Taliban. Brennan focused most on Hezbollah and painted a remarkable picture of the group:

Whether or not Brennan was the source for the Washington Post report, one can detect the similarity of the viewpoints that are evidently, as per the WaPo report, being raised by “some White House advisers.”

The main points of the argument are familiar to anyone who’s kept up with the scholarly literature on Hezbollah, especially the proponents of the so-called “Lebanonization” theory, chief among whom is Augustus Richard Norton. This view holds that Hezbollah has “evolved” from a terrorist group into a mainstream political party.

In order to sustain this argument, its proponents have often resorted to distancing Hezbollah from terrorist activity dating after its involvement in Lebanese politics, or, at the very least, minimizing it. This had been the norm in Hezbollah scholarship prior to the assassination of Imad Mughniyeh in February 2008.

Brennan does the same in his 2008 article, claiming rather remarkably, that “the evolution” of Hezbollah into a political player was simultaneous with “a marked reduction in terrorist attacks carried out by the organization.” Moreover, “increasing Hezbollah’s stake” in the Lebanese political process has had no effect on Hezbollah’s military operations, as evident form their involvement in Iraq, and Yemen, Egypt and Azerbaijan (as noted by Matt Levitt in his post).

However, what’s more problematic is the definition of “political participation.” Hezbollah has made a mockery of Lebanon’s constitution and parliamentary political traditions. Needless to say, the idea of a sectarian group with an arsenal that rivals that of an army, and with external foreign connections and networks, “participating in politics in a tightly balanced sectarian society” is itself an absurdity.

Furthermore, those who make this argument miss the point of Hezbollah’s political participation: it is precisely in order to protect its military autonomy. This was articulated by a Hezbollah spokesman in a 2007 interview with the International Crisis Group: “Paradoxically, some want us to get involved in the political process in order to neutralise us. In fact, we intend to get involved—but precisely in order to protect the strategic choice of resistance.”

Hezbollah has used its weapons in order to bend the political system to fit its agenda and has intimidated its political rivals by force of arms. As the author of the ICG report, Patrick Haenni, put it: “Hezbollah realized that they had [to be internally involved to a greater extent], but the issue was still to secure their weapons…. Hezbollah has a real interest in making the state part of its global project.”

The flawed understanding of the nature of Hezbollah has led people like Brennan to posit the existence of various “wings” in Hezbollah: “extremists” vs. “moderates” and those who supposedly “renounce terrorism” vs. those who support it. While this illusory categorization has not been translated into U.S. policy, it has, alas, become British policy. Ironically, Hezbollah officials have publicly mocked this kind of artificial dichotomies.

This fundamental misunderstanding of the group is captured in the wording of the Washington Post report, which described Hezbollah as “the armed Lebanese political movement.” That has it backwards. To quote Ahmad Nizar Hamzeh, Hezbollah is “first and foremost a jihadi movement that engages in politics, and not a political party that conducts jihad.” One must qualify that further by adding what Na’im Qassem wrote in his book, that the jurisprudent (al-wali al-faqih)—i.e., Iran’s Supreme Guide, Ali Khamenei—”alone possesses the authority to decide war and peace,” and matters of jihad. Therefore, in effect Hezbollah is a light infantry division of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps.

That’s not the kind of model the US wants to see in Afghanistan.

Tony Badran is research fellow with the Center for Terrorism Research at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies.