Week 12: On the Power of the Pen

ø

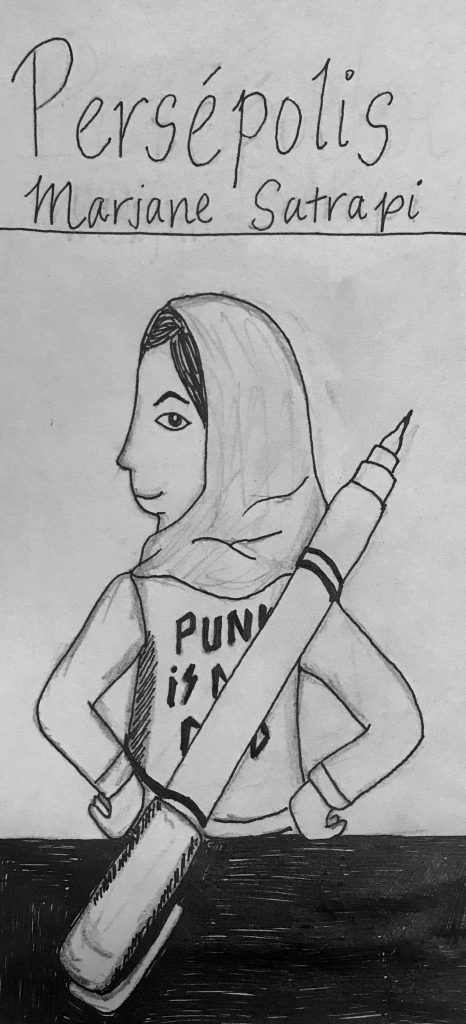

This is a pen and ink piece that was inspired by Persepolis, by Marjane Satrapi. Specifically, the idea behind this is that it is an alternative cover to the graphic novel than the original, focusing on the importance of the medium that Satrapi used as a form of empowerment in telling her story. The original novel cover features a young Satrapi staring point blank at the camera from across the table. Her body language, with her crossed arms and frowning expression, express feelings of distress and discomfort, which are representative of her experience growing up during the Iranian Islamic Revolution. During the section in which Satrapi struggled to smoke a cigarette for the first time, she reflects on how she felt that this was her turning point into adulthood – which I’m sure, to a kid smoking a cigarette for the first time, is a total symbolic moment, but I would like to argue that Satrapi was slowly losing the innocence of childhood much earlier: through the bombings, killings, and various horrifying events that she and her family witnessed; through the difficult questions she constantly asked her parents and friends; through her insistence to protest alongside her mother and father, and many more. As a result, due to the Revolution, Satrapi was forced to grow up much sooner than a normal child her age, a juxtaposition that I was constantly aware of due to Satrapi’s usage of the graphic novel: you could see that Satrapi was still a child, as illustrated, but the questions and thoughts she was expressing were so beyond her age. As a result, this illustration shows the agency that Satrapi was able to have after a situation in which many of the decisions about her life growing up were out of her hands – she was forced to wear a hijab, forced to leave her family, and so on. The telling of her childhood through a medium that is able to contrast the innocence of childhood with her intense emotional backstory was immensely effective, and so this cover represents that: her facial expressions and upright body posture are exuding confidence, and her “weapon of choice” against the trauma of her childhood is her micron pen.