In many states of the USA the argument for Medical Marijuana has not yet prevailed. Though opinion against its medicinal use may be grounded in misinformation and prejudice, it is yet true that the Supreme Court has no reason to expend its valuable authority in preventing Congress from respecting and responding to what is still a dominant national sensibility. The Supreme Court’s decision forces Medical Marijuana advocates to move the focus of their educational efforts to the national legislature. This may prove in the end to be a good thing, though in the mean time doctors and patients will feel the pressure of the law as an additional goad to present their case.

In many states of the USA the argument for Medical Marijuana has not yet prevailed. Though opinion against its medicinal use may be grounded in misinformation and prejudice, it is yet true that the Supreme Court has no reason to expend its valuable authority in preventing Congress from respecting and responding to what is still a dominant national sensibility. The Supreme Court’s decision forces Medical Marijuana advocates to move the focus of their educational efforts to the national legislature. This may prove in the end to be a good thing, though in the mean time doctors and patients will feel the pressure of the law as an additional goad to present their case.

***

The FDA better close their eyes and cover their ears….

Clinical trial to be published in the Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences

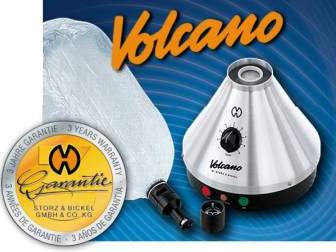

calls the Volcano Vaporizer a “safe and effective” cannabinoid delivery

system:

“The goal of this study was to evaluate the performance of the Volcano

vaporizer in terms of reproducible delivery of the bioactive cannabinoid

tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) by using pure cannabinoid preparations, so that

it could be used in a clinical trial.

“Our results show that with the Volcano a safe and effective cannabinoid

delivery system seems to be available to patients. The final pulmonal uptake

of THC is comparable to the smoking of cannabis, while avoiding the

respiratory disadvantages of smoking.”

—————————————————————————-

J Pharm Sci. 2006 Apr 24

Evaluation of a vaporizing device (Volcano(R)) for the pulmonary

administration of tetrahydrocannabinol.

Hazekamp A, Ruhaak R, Zuurman L, van Gerven J, Verpoorte R.

Division of Pharmacognosy, Institute of Biology, Leiden University, Leiden,

The Netherlands.

What is currently needed for optimal use of medicinal cannabinoids is a

feasible, nonsmoked, rapid-onset delivery system. Cannabis “vaporization” is

a technique aimed at suppressing irritating respiratory toxins by heating

cannabis to a temperature where active cannabinoid vapors form, but below

the point of combustion where smoke and associated toxins are produced. The

goal of this study was to evaluate the performance of the Volcano vaporizer

in terms of reproducible delivery of the bioactive cannabinoid

tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) by using pure cannabinoid preparations, so that

it could be used in a clinical trial. By changing parameters such as

temperature setting, type of evaporation sample and balloon volume, the

vaporization of THC was systematically improved to its maximum, while

preventing the formation of breakdown products of THC, such as cannabinol or

delta-8-THC. Inter- and intra-device variability was tested as well as

relationship between loaded- and delivered dose. It was found that an

average of about 54% of loaded THC was delivered into the balloon of the

vaporizer, in a reproducible manner. When the vaporizer was used for

clinical administration of inhaled THC, it was found that on average 35% of

inhaled THC was directly exhaled again. Our results show that with the

Volcano a safe and effective cannabinoid delivery system seems to be

available to patients. The final pulmonal uptake of THC is comparable to the

smoking of cannabis, while avoiding the respiratory disadvantages of

smoking. (c) 2006 Wiley-Liss, Inc. and the American Pharmacists Association

J Pharm Sci 95:1308-1317, 2006.

***

Medical marijuana

Reefer madness

Apr 27th 2006

>From The Economist print edition

Marijuana is medically useful, whether politicians like it or not

IF CANNABIS were unknown, and bioprospectors were suddenly to find it in

some remote mountain crevice, its discovery would no doubt be hailed as

a medical breakthrough. Scientists would praise its potential for

treating everything from pain to cancer, and marvel at its rich

pharmacopoeia‹many of whose chemicals mimic vital molecules in the human

body. In reality, cannabis has been with humanity for thousands of years

and is considered by many governments (notably America’s) to be a

dangerous drug without utility. Any suggestion that the plant might be

medically useful is politically controversial, whatever the science

says. It is in this context that, on April 20th, America’s Food and Drug

Administration (FDA) issued a statement saying that smoked marijuana has

no accepted medical use in treatment in the United States.

The statement is curious in a number of ways. For one thing, it

overlooks a report made in 1999 by the Institute of Medicine (IOM), part

of the National Academy of Sciences, which came to a different

conclusion. John Benson, a professor of medicine at the University of

Nebraska who co-chaired the committee that drew up the report, found

some sound scientific information that supports the medical use of

marijuana for certain patients for short periods‹even for smoked marijuana.

This is important, because one of the objections to marijuana is that,

when burned, its smoke contains many of the harmful things found in

tobacco smoke, such as carcinogenic tar, cyanide and carbon monoxide.

Yet the IOM report supports what some patients suffering from multiple

sclerosis, AIDS and cancer‹and their doctors‹have known for a long time.

This is that the drug gives them medicinal benefits over and above the

medications they are already receiving, and despite the fact that the

smoke has risks. That is probably why several studies show that many

doctors recommend smoking cannabis to their patients, even though they

are unable to prescribe it. Patients then turn to the black market for

their supply.

Another reason the FDA statement is odd is that it seems to lack common

sense. Cannabis has been used as a medicinal plant for millennia. In

fact, the American government actually supplied cannabis as a medicine

for some time, before the scheme was shut down in the early 1990s.

Today, cannabis is used all over the world, despite its illegality, to

relieve pain and anxiety, to aid sleep, and to prevent seizures and

muscle spasms. For example, two of its long-advocated benefits are that

it suppresses vomiting and enhances appetite‹qualities that AIDS

patients and those on anti-cancer chemotherapy find useful. So useful,

in fact, that the FDA has licensed a drug called Marinol, a synthetic

version of one of the active ingredients of

marijuana‹delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). Unfortunately, many users

of Marinol complain that it gets them high (which isn’t what they

actually want) and is not nearly as effective, nor cheap, as the real

weed itself.

This may be because Marinol is ingested into the stomach, meaning that

it is metabolised before being absorbed. Or it may be because the

medicinal benefits of cannabis come from the synergistic effect of the

multiplicity of chemicals it contains.

Just what have you been smoking?

THC is the best known active ingredient of cannabis, but by no means the

only one. At the last count, marijuana was known to contain nearly 70

different cannabinoids, as THC and its cousins are collectively known.

These chemicals activate receptor molecules in the human body,

particularly the cannabinoid receptors on the surfaces of some nerve

cells in the brain, and stimulate changes in biochemical activity. But

the details often remain vague‹in particular, the details of which

molecules are having which clinical effects.

More clinical research would help. In particular, the breeding of

different varieties of cannabis, with different mixtures of

cannabinoids, would enable researchers to find out whether one variety

works better for, say, multiple sclerosis-related spasticity while

another works for AIDS-related nerve pain. However, in the United

States, this kind of work has been inhibited by marijuana’s illegality

and the unwillingness of the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) to

license researchers to grow it for research.

Since 2001, for example, Lyle Craker, a researcher at the University of

Massachusetts, has been trying to obtain a licence from the DEA to grow

cannabis for use in clinical research. After years of prevarication, and

pressure on the DEA to make a decision, Dr Craker’s application was

turned down in 2004. Today, the saga continues and a DEA judge (who

presides over a quasi-judicial process within the agency) is hearing an

appeal, which could come to a close this summer. Dr Craker says that his

situation is like that described in Joseph Heller’s novel, ³Catch 22².

³We can say that this has no medical benefit because no tests have been

done, and then we refuse to let you do any tests. The US has gotten into

a bind, it has made cannabis out to be such a villain that people

blindly say Œno¹.²

Anjuli Verma, the advocacy director of the American Civil Liberties

Union (ACLU), a group helping Dr Craker fight his appeal, says that even

if the DEA judge rules in their favour, the agency’s chief administrator

can still decide whether to allow the application. And, as she points

out, the DEA is a political organisation charged with enforcing the drug

laws. So, she says, the ACLU is in this for the long haul, and is

already prepared for another appeal‹one that would be heard in a federal

court in the normal judicial system.

Ms Verma’s view of the FDA’s statement is that other arms of government

are putting pressure on the agency to make a public pronouncement that

conforms with drug ideology as promulgated by the White House, the DEA

and a number of vocal anti-cannabis congressmen. In particular, the

federal government has been rattled in recent years by the fact that

eleven states have passed laws allowing the medical use of marijuana. In

this context it is notable that the FDA’s statement emphasises that it

is smoked marijuana which has not gone through the process necessary to

make it a prescription drug. (Nor would it be likely to, with all of the

harmful things in the smoke.) The statement’s emphasis on smoked

marijuana is important because it leaves the door open for the agency to

approve other methods of delivery.

High hopes

Donald Abrams, a professor of clinical medicine at the University of

California, San Francisco, has been working on one such option. He is

allowed by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (the only legal supplier

of cannabis in the United States) to do research on a German nebuliser

that heats cannabis to the point of vaporisation, where it releases its

cannabinoids without any of the smoke of a spliff, and with fewer

carcinogens.

That is encouraging. But it does not address the wider question of which

cannabinoids are doing what. For that, researchers need to be able to do

their own plant-breeding programmes.

In America, this is impossible. But it is happening in other countries.

In 1997, for example, the British government asked Geoffrey Guy, the

executive chairman and founder of GW Pharmaceuticals, to come up with a

programme to develop cannabis into a pharmaceutical product.

In the intervening years, GW has assembled a ³library² of more than 300

varieties of cannabis, and obtained plant-breeder’s rights on between 30

and 40 of these. It has found the genes that control cannabinoid

production and can specify within strict limits the seven or eight

cannabinoids it is most interested in. And it knows how to crossbreed

its strains to get the mixtures it wants.

Nor is this knowledge merely academic. Last year, GW gained approval in

Canada for the use of its first drug, Sativex, which is an extract of

cannabis sprayed under the tongue that is designed for the relief of

neuropathic pain in multiple sclerosis. Sativex is also available to a

more limited degree in Spain and Britain, and is in clinical trials for

other uses, such as relieving the pain of rheumatoid arthritis.

At the start of this year, the company made the first step towards

gaining regulatory approval for Sativex in America when the FDA accepted

it as a legitimate candidate for clinical trials. But there is still a

long way to go.

And that delay raises an important point. Once available, a

well-formulated and scientifically tested drug should knock a herbal

medicine into a cocked hat. No one would argue for chewing willow bark

when aspirin is available. But, in the meantime, there is unmet medical

need that, as the IOM report pointed out, could easily and cheaply be

met‹if the American government cared more about suffering and less about

posturing.