(“And also Bud Light.”)

In my last two posts I’ve been writing about my attempt to convince a group of sophomores with no background in my field that there has been a shift to the algorithmic allocation of attention — and that this is important. In this post I’ll respond to a student question. My favorite: “Sandvig says that algorithms are dangerous, but what are the the most serious repercussions that he envisions?” What is the coming social media apocalypse we should be worried about?

This is an important question because people who study this stuff are NOT as interested in this student question as they should be. Frankly, we are specialists who study media and computers and things — therefore we care about how algorithms allocate attention among cultural products almost for its own sake. Because this is the central thing that we study, we don’t spend a lot of time justifying it.

And our field’s most common response to the query “what are the dangers?” often lacks the required sense of danger. The most frequent response is: “extensive personalization is bad for democracy.” (a.k.a. Pariser’s “filter bubble,” Sunstein’s “egocentric” Internet, and so on). This framing lacks a certain house-on-fire urgency, doesn’t it?

(sarcastic tone:) “Oh, no! I’m getting to watch, hear, and read exactly what I want. Help me! Somebody do something!”

Sometimes (as Hindman points out) the contention is the opposite, that Internet-based concentration is bad for democracy. But remember that I’m not speaking to political science majors here. The average person may not be as moved by an abstract, long-term peril to democracy as the average political science professor. As David Weinberger once said after I warned about the increasing reliance on recommendation algorithms, “So what?” Personalization sounds like a good thing.

As a side note, the second most frequent response I see is that algorithms are now everywhere. And they work differently than what came before. This also lacks a required sense of danger! Yes, they’re everywhere, but if they are a good thing…

So I really like this question “what are the the most serious repercussions?” because I think there are some elements of the shift to attention-sorting algorithms that are genuinely “dangerous.” I can think of at least two, probably more, and they don’t get enough attention. In the rest of this post I’ll spell out the first one which I’ll call “corrupt personalization.”

Here we go.

Common-sense reasoning about algorithms and culture tells us that the purveyors of personalized content have the same interests we do. That is, if Netflix started recommending only movies we hate or Google started returning only useless search results we would stop using them. However: Common sense is wrong in this case. Our interests are often not the same as the providers of these selection algorithms. As in my last post, let’s work through a few concrete examples to make the case.

In this post I’ll use Facebook examples, but the general problem of corrupt personalization is present on all of our media platforms in wide use that employ the algorithmic selection of content.

(1) Facebook “Like” Recycling

(Image from ReadWriteWeb.)

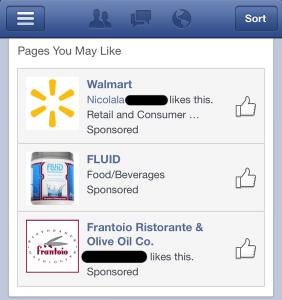

On Facebook, in addition to advertisements along the side of the interface, perhaps you’ve noticed “featured,” “sponsored,” or “suggested” stories that appear inside your news feed, intermingled with status updates from your friends. It could be argued that this is not in your interest as a user (did you ever say, “gee, I’d like ads to look just like messages from my friends”?), but I have bigger fish to fry.

Many ads on Facebook resemble status updates in that there can be messages endorsing the ads with “likes.” For instance, here is an older screenshot from ReadWriteWeb:

Another example: a “suggested” post was mixed into my news feed just this morning. recommending World Cup coverage on Facebook itself. It’s a Facebook ad for Facebook, in other words. It had this intriguing addendum:

So, wait… I have hundreds of friends and eleven of them “like” Facebook? Did they go to http://www.facebook.com and click on a button like this:

But facebook.com doesn’t even have a “Like” button! Did they go to Facebook’s own Facebook page (yes, there is one) and click “Like”? I know these people and that seems unlikely. And does Nicolala really like Walmart? Hmmm…

What does this “like” statement mean? Welcome to the strange world of “like” recycling. Facebook has defined “like” in ways that depart from English usage. For instance, in the past Facebook has determined that:

- Anyone who clicks on a “like” button is considered to have “liked” all future content from that source. So if you clicked a “like” button because someone shared a “Fashion Don’t” from Vice magazine, you may be surprised when your dad logs into Facebook three years later and is shown a current sponsored story from Vice.com like “Happy Masturbation Month!” or “How to Make it in Porn” with the endorsement that you like it. (Vice.com example is from Craig Condon [NSFW].)

- Anyone who “likes” a comment on a shared link is considered to “like” wherever that link points to. a.k.a. “‘liking a share.” So if you see a (real) FB status update from a (real) friend and it says: “Yuck! The McLobster is a disgusting product idea!” and your (real) friend include a (real) link like this one — that means if you clicked “like” your friends may see McDonald’s ads in the future that include the phrase “(Your Name) likes McDonalds.” (This example is from ReadWriteWeb.)

This has led to some interesting results, like dead people “liking” current news stories on Facebook.

There is already controversy about advertiser “like” inflation, “like” spam, and fake “likes,” — and these things may be a problem too, but that’s not what we are talking about here. In the examples above the system is working as Facebook designed it to. A further caveat: note that the definition of “like” in Facebook’s software changes periodically and when they are sued. Facebook now has an opt-out setting for the above two “features.”

But these incendiary examples are exceptional fiascoes — on the whole the system probably works well. You likely didn’t know that your “like” clicks are merrily producing ads on your friends pages and in your name because you cannot see them. These “stories” do not appear on your news feed and cannot be individually deleted.

Unlike the examples from my last post you can’t quickly reproduce these results with certainty on your own account. Still, if you want to try, make a new Facebook account under a fake name (warning! dangerous!) and friend your real account. Then use the new account to watch your status updates.

Why would Facebook do this? Obviously it is a controversial practice that is not going to be popular with users. Yet Facebook’s business model is to produce attention for advertisers, not to help you — silly rabbit. So they must have felt that using your reputation to produce more ad traffic from your friends was worth the risk of irritating you. Or perhaps they thought that the practice could be successfully hidden from users — that strategy has mostly worked!

In sum this is a personalization scheme that does not serve your goals, it serves Facebook’s goals at your expense.

(2) “Organic” Content

This second group of examples concerns content that we consider to be “not advertising,” a.k.a. “organic” content. Funnily enough, algorithmic culture has produced this new use of the word “organic” — but has also made the boundary between “advertising” and “not advertising” very blurry.

The general problem is that there are many ways in which algorithms act as mixing valves between things that can be easily valued with money (like ads) and things that can’t. And this kind of mixing is a normative problem (what should we do) and not a technical problem (how do we do it).

For instance, for years Facebook has encouraged nonprofits, community-based organizations, student clubs, other groups, and really anyone to host content on facebook.com. If an organization creates a Facebook page for itself, the managers can update the page as though it were a profile.

Most page managers expect that people who “like” that page get to see the updates… which was true until January of this year. At that time Facebook modified its algorithm so that text updates from organizations were not widely shared. This is interesting for our purposes because Facebook clearly states that it wants page operators to run Facebook ad campaigns, and not to count on getting traffic from “organic” status updates, as it will no longer distribute as many of them.

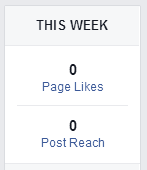

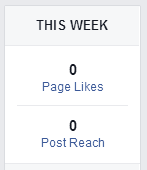

This change likely has a very differential effect on, say, Nike‘s Facebook page, a small local business‘s Facebook page, Greenpeace International‘s Facebook page, and a small local church congregation‘s Facebook page. If you start a Facebook page for a school club, you might be surprised that you are spending your labor writing status updates that are never shown to anyone. Maybe you should buy an ad. Here’s an analytic for a page I manage:

The impact isn’t just about size — at some level businesses might expect to have to insert themselves into conversations via persuasive advertising that they pay for, but it is not as clear that people expect Facebook to work this way for their local church or other domains of their lives. It’s as if on Facebook, people were using the yellow pages but they thought they were using the white pages. And also there are no white pages.

(Oh, wait. No one knows what yellow pages and white pages are anymore. Scratch that reference, then.)

No need to stop here, in the future perhaps Facebook can monetize my family relationships. It could suggest that if I really want anyone to know about the birth of my child, or I really want my “insightful” status updates to reach anyone, I should turn to Facebook advertising.

Let me also emphasize that this mixing problem extends to the content of our personal social media conversations as well. A few months back, I posted a Facebook status update that I thought was humorous. I shared a link highlighting the hilarious product reviews for the Bic “Cristal For Her” ballpoint pen on Amazon. It’s a pen designed just for women.

The funny thing is that I happened to look at a friend of mine’s Facebook feed over their shoulder, and my status update didn’t go away. It remained, pegged at the top of my friend’s news feed, for as long as 14 days in one instance. What great exposure for my humor, right? But it did seem a little odd… I queried my other friends on Facebook and some confirmed that the post was also pegged at the top of their news feed.

I was unknowingly participating in another Facebook program that converts organic status updates into ads. It does this by changing their order in the news feed and adding the text “Sponsored” in light gray, which is very hard to see. Otherwise at least some updates are not changed. I suspect Facebook’s algorithm thought I was advertising Amazon (since that’s where the link pointed), but I am not sure.

This is similar to Twitter’s “Promoted Tweets” but there is one big difference. In the Facebook case the advertiser promotes content — my content — that they did not write. In effect Facebook is re-ordering your conversations with your friends and family on the basis of whether or not someone mentioned Coke, Levi’s, and Anheuser Busch (confirmed advertisers in the program).

Sounds like a great personal social media strategy there–if you really want people to know about your forthcoming wedding, maybe just drop a few names? Luckily the algorithms aren’t too clever about this yet so you can mix up the word order for humorous effect.

(Facebook status update:) “I am so delighted to be engaged to this wonderful woman that I am sitting here in my Michelob drinking a Docker’s Khaki Collection. And also Coke.”

Be sure to use links. I find the interesting thing about this mixing of the commercial and non-commercial to be that it sounds to my ears like some sort of corny, unrealistic science fiction scenario and yet with the current Facebook platform I believe the above example would work. We are living in the future.

So to recap, if Nike makes a Facebook page and posts status updates to it, that’s “organic” content because they did not pay Facebook to distribute it. Although any rational human being would see it as an ad. If my school group does the same thing, that’s also organic content, but they are encouraged to buy distribution — which would make it inorganic. If I post a status update or click “like” in reaction to something that happens in my life and that happens to involve a commercial product, my action starts out as organic, but then it becomes inorganic (paid for) because a company can buy my words and likes and show them to other people without telling me. Got it? This paragraph feels like we are rethinking CHEM 402.

The upshot is that control of the content selection algorithm is used by Facebook to get people to pay for things they wouldn’t expect to pay for, and to show people personalized things that they don’t think are paid for. But these things were in fact paid for. In sum this is again a scheme that does not serve your goals, it serves Facebook’s goals at your expense.

The Danger: Corrupt Personalization

With these concrete examples behind us, I can now more clearly answer this student question. What are the most serious repercussions of the algorithmic allocation of attention?

I’ll call this first repercussion “corrupt personalization” after C. Edwin Baker. (Baker, a distinguished legal philosopher, coined the phrase “corrupt segmentation” in 1998 as an extension of the theories of philosopher Jürgen Habermas.)

Here’s how it works: You have legitimate interests that we’ll call “authentic.” These interests arise from your values, your community, your work, your family, how you spend your time, and so on. A good example might be that as a person who is enrolled in college you might identify with the category “student,” among your many other affiliations. As a student, you might be authentically interested in an upcoming tuition increase or, more broadly, about the contention that “there are powerful forces at work in our society that are actively hostile to the college ideal.”

However, you might also be authentically interested in the fact that your cousin is getting married. Or in pictures of kittens.

Corrupt personalization is the process by which your attention is drawn to interests that are not your own. This is a little tricky because it is impossible to clearly define an “authentic” interest. However, let’s put that off for the moment.

In the prior examples we saw some (I hope) obvious places where my interests diverged from that of algorithmic social media systems. Highlights for me were:

- When I express my opinion about something to my friends and family, I do not want that opinion re-sold without my knowledge or consent.

- When I explicitly endorse something, I don’t want that endorsement applied to other things that I did not endorse.

- If I want to read a list of personalized status updates about my friends and family, I do not want my friends and family sorted by how often they mention advertisers.

- If a list of things is chosen for me, I want the results organized by some measure of goodness for me, not by how much money someone has paid.

- I want paid content to be clearly identified.

- I do not want my information technology to sort my life into commercial and non-commercial content and systematically de-emphasize the noncommercial things that I do, or turn these things toward commercial purposes.

More generally, I think the danger of corrupt personalization is manifest in three ways.

- Things that are not necessarily commercial become commercial because of the organization of the system. (Merton called this “pseudo-gemeinschaft,” Habermas called it “colonization of the lifeworld.”)

- Money is used as a proxy for “best” and it does not work. That is, those with the most money to spend can prevail over those with the most useful information. The creation of a salable audience takes priority over your authentic interests. (Smythe called this the “audience commodity,” it is Baker’s “market filter.”)

- Over time, if people are offered things that are not aligned with their interests often enough, they can be taught what to want. That is, they may come to wrongly believe that these are their authentic interests, and it may be difficult to see the world any other way. (Similar to Chomsky and Herman’s [not Lippman’s] arguments about “manufacturing consent.”)

There is nothing inherent in the technologies of algorithmic allocation that is doing this to us, instead the economic organization of the system is producing these pressures. In fact, we could design a system to support our authentic interests, but we would then need to fund it. (Thanks, late capitalism!)

To conclude, let’s get some historical perspective. What are the other options, anyway? If cultural selection is governed by computer algorithms now, you might answer, “who cares?” It’s always going to be governed somehow. If I said in a talk about “algorithmic culture” that I don’t like the Netflix recommender algorithm, what is supposed to replace it?

This all sounds pretty bad, so you might think I am asking for a return to “pre-algorithmic” culture: Let’s reanimate the corpse of Louis B. Mayer and he can decide what I watch. That doesn’t seem good either and I’m not recommending it. We’ve always had selection systems and we could even call some of the earlier ones “algorithms” if we want to. However, we are constructing something new and largely unprecedented here and it isn’t ideal. It isn’t that I think algorithms are inherently dangerous, or bad — quite the contrary. To me this seems like a case of squandered potential.

With algorithmic culture, computers and algorithms are allowing a new level of real-time personalization and content selection on an individual basis that just wasn’t possible before. But rather than use these tools to serve our authentic interests, we have built a system that often serves a commercial interest that is often at odds with our interests — that’s corrupt personalization.

If I use the dominant forms of communication online today (Facebook, Google, Twitter, YouTube, etc.) I can expect content customized for others to use my name and my words without my consent, in ways I wouldn’t approve of. Content “personalized” for me includes material I don’t want, and obscures material that I do want. And it does so in a way that I may not be aware of.

This isn’t an abstract problem like a long-term threat to democracy, it’s more like a mugging — or at least a confidence game or a fraud. It’s violence being done to you right now, under your nose. Just click “like.”

In answer to your question, dear student, that’s my first danger.

* * *

ADDENDUM:

This blog post is already too long, but here is a TL;DR addendum for people who already know about all this stuff.

I’m calling this corrupt personalization because I cant just apply Baker’s excellent ideas about corrupt segments — the world has changed since he wrote them. Although this post’s reasoning is an extension of Baker, it is not a straightforward extension.

Algorithmic attention is a big deal because we used to think about media and identity using categories, but the algorithms in wide use are not natively organized that way. Baker’s ideas were premised on the difference between authentic and inauthentic categories (“segments”), yet segments are just not that important anymore. Bermejo calls this the era of post-demographics.

Advertisers used to group demographics together to make audiences comprehensible, but it may no longer be necessary to buy and sell demographics or categories as they are a crude proxy for purchasing behavior. If I want to sell a Subaru, why buy access to “Brite Lights, Li’l City” (My PRIZM marketing demographic from the 1990s) when I can directly detect “intent to purchase a station wagon” or “shopping for a Subaru right now”? This complicates Baker’s idea of authentic segments quite a bit. See also Gillespie’s concept of calculated publics.

Also Baker was writing in an era where content was inextricably linked to advertising because it was not feasible to decouple them. But today algorithmic attention sorting has often completely decoupled advertising from content. Online we see ads from networks that are based on user behavior over time, rather than what content the user is looking at right now. The relationship between advertising support and content is therefore more subtle than in the previous era, and this bears more investigation.

Okay, okay I’ll stop now.

(This post was cross-posted to The Social Media Collective.)