Guide released on good practices for university open-access policies

October 17th, 2012

I’m pleased to forward on the announcement that the Harvard Open Access Project has just released an initial version of a guide on “good practices for university open-access policies”. It was put together by Peter Suber and myself with help from many, including Ellen Finnie Duranceau, Ada Emmett, Heather Joseph, Iryna Kuchma, and Alma Swan. It has already received endorsements from the Coalition of Open Access Policy Institutions (COAPI), Confederation of Open Access Repositories (COAR), Electronic Information for Libraries (EIFL), Enabling Open Scholarship (EOS), Harvard Open Access Project (HOAP), Open Access Scholarly Information Sourcebook (OASIS), Scholarly Publishing and Academic Resources Coalition (SPARC), and SPARC Europe.

The official announcement is provided below, replicated from the Berkman Center announcement. Read the rest of this entry »

For Ada Lovelace Day 2012: Karen Spärck Jones

October 16th, 2012

|

| Karen Spärck Jones, 1935-2007 |

In honor of Ada Lovelace Day 2012, I write about the only female winner of the Lovelace Medal awarded by the British Computer Society for “individuals who have made an outstanding contribution to the understanding or advancement of Computing”. Karen Spärck Jones was the 2007 winner of the medal, awarded shortly before her death. She also happened to be a leader in my own field of computational linguistics, a past president of the Association for Computational Linguistics. Because we shared a research field, I had the honor of knowing Karen and the pleasure of meeting her on many occasions at ACL meetings.

One of her most notable contributions to the field of information retrieval was the idea of inverse document frequency. Well before search engines were a “thing”, Karen was among the leaders in figuring out how such systems should work. Already in the 1960’s there had arisen the idea of keyword searching within sets of documents, and the notion that the more “hits” a document receives, the higher ranked it should be. Karen noted in her seminal 1972 paper “A statistical interpretation of term specificity and its application in retrieval” that not all hits should be weighted equally. For terms that are broadly distributed throughout the corpus, their occurrence in a particular document is less telling than occurrence of terms that occur in few documents. She proposed weighting each term by its “inverse document frequency” (IDF), which she defined as log(N/(n + 1)) where N is the number of documents and n the number of documents containing the keyword under consideration. When the keyword occurs in all documents, IDF approaches 1 for large N, but as the keyword occurs in fewer and fewer documents (making it a more specific and presumably more important keyword), IDF rises. The two notions of weighting (frequency of occurrence of the keyword together with its specificity as measured by inverse document frequency) are combined multiplicatively in the by now standard tf*idf metric; tf*idf or its successors underlie essentially all information retrieval systems in use today.

In Karen’s interview for the Lovelace Medal, she opined that “Computing is too important to be left to men.” Ada Lovelace would have agreed.

Open Access Week 2012 at Harvard

October 8th, 2012

|

| …set the default… |

Here’s what’s on deck at Harvard for Open Access Week 2012 (reproduced from the OSC announcement).

From October 22 through October 28, Harvard University is joining hundreds of other institutions of higher learning to celebrate Open Access Week, a global event for the promotion of free, immediate online access to scholarly research.

Harvard will participate in OA Week locally by offering two public events that engage this year’s theme, “Set the default to open access.”

On October 23rd at 12:30 p.m., the Berkman Center for Internet & Society and the Office for Scholarly Communication will host a forum entitled “How to Make Your Research Open Access (Whether You’re at Harvard or Not).” OA advocates Peter Suber and Stuart Shieber will headline the session, answering questions on any aspect of open access and recommending concrete steps for making your work open access. The event will be held at the Berkman Center, 23 Everett Street, 2nd Floor. The Berkman Center will also stream the discussion live online. See the Berkman Center website for more information and to RSVP.

On October 24, a panel of experts will consider efforts by the National Institutes of Health to ensure public access to the published results of federally funded research. “Open Access to Health Research: Future Directions for the NIH Public Access Policy” will feature a discussion of the challenges and opportunities for increasing compliance with the NIH policy. The event, co-sponsored by the Office for Scholarly Communication, Right to Research Coalition, and Universities Allied for Essential Medicines, will be held at the Harvard Law School in Hauser Hall, room 104. More information is available at the Petrie-Flom Center website.

Is the Harvard open-access policy legally sound?

September 17th, 2012

|

| …evidenced by a written instrument… “To Sign a Contract 3” image by shho. Used by permission. |

The idea behind rights-retention open-access policies is, as this year’s OA Week slogan goes, to “set the default to open access”. Traditionally, authors retained rights to their scholarly articles only if they expressly negotiated with their publishers to do so. Rights-retention OA policies—like those at Harvard and many other universities, and as exemplified by our Model Policy—change the default so that authors retain open-access rights unless they expressly opt out.

The technique the policies use is a kind of “rights loop”:

- The policy has the effect of granting a transferable nonexclusive license to the university as soon as copyright vests in the article. This license precedes and survives any later transfer to a publisher.

- The university can grant the licensed rights back to the author (as well as making use of them itself, primarily through distribution of the article from a repository).

The author retains rights by using the university as a kind of holding area for those rights. The waiver provision, under sole control of the author, means that this rights retention is a default, but defeasible.

This at least was the theory, but what are the legalities of the matter? In designing Harvard’s OA policy, we spent a lot of time trying to make sure that the reality would match the theory. Now, Eric Priest, a professor at the University of Oregon School of Law, has done a detailed analysis of the policy (forthcoming in the Northwestern Journal of Technology and Intellectual Property and available open access from SSRN) to determine if the legal premise of the policy is sound. The bottom line: It is. Those charged with writing such policies will want to read the article in detail. I’ll only give a summary of the conclusions here, and mention how at Harvard we have been optimizing our own implementation of the policy to further strengthen its legal basis.

Priest’s conclusion is well summarized in the following quote:

The principal aim of this Article has been to analyze the legal effect of “Harvard-style” open access permission mandates. This required first analyzing whether scholars are the legal authors (and therefore initial owners) of their scholarly articles under the Copyright Act’s work made for hire rules. It then required determining whether a permission mandate in fact vests, as its terms suggest, nonexclusive licenses in the university for all scholarly articles created by its faculty. Lastly, this analysis required determining whether those licenses survive after the faculty member who writes the article transfers copyright ownership to a publisher. As the foregoing analysis shows, in the Author’s opinion the answer to all three of these questions is “yes”: scholars should be deemed the authors of their works, and permission mandates create in universities effective, durable nonexclusive licenses to archive and distribute faculty scholarship and permit the university to license others to do the same.

Although Priest’s analysis agrees with our own that the policies work in and of themselves (at least those using the wording that we have promulgated in our own policies at Harvard and in our Model Policy), he notes various ways in which the arguments for the various legal aspects can be even further strengthened, revolving around Section 205(e) of the Copyright Act, which holds that “a nonexclusive license, whether recorded or not, prevails over a conflicting transfer of copyright ownership if the license is evidenced by a written instrument signed by the owner of the rights licensed”.

Priest argues at length and in detail that no individual written instrument is required for the survival of the nonexclusive license. But obtaining such an individual written instrument certainly can’t hurt. In fact, at Harvard we do obtain such a written instrument. There are two paths by which articles enter the DASH repository for distribution pursuant to an OA policy: Authors can deposit them themselves, or someone (a faculty assistant or a member of the Office for Scholarly Communication staff) can deposit them on behalf of the authors. In the first case, the author assents (via a click-through statement) to an affirmation of the nonexclusive license:

I confirm my grant to Harvard of a non-exclusive license with respect to my scholarly articles, including the Work, as set forth in the open access policy found at http://osc.hul.harvard.edu/ that was adopted by the Harvard Faculty or School of which I am a member.

In the second case, our workflow requires that authors have provided us with an “Assistance Authorization Form”, available either as a click-through web form or print version to be signed. This form gives the OSC and any named assistants the right to act on the faculty member’s behalf as depositor, and also provides assent to the statement

In addition, if I am a member of a Harvard Faculty or School that has adopted an open access policy found at http://osc.hul.harvard.edu/, this confirms my grant to Harvard of a non-exclusive license with respect to my scholarly articles as set forth in that policy.

Authors need only provide this form once; thereafter, we can act on their behalf in depositing articles.

Thus, no matter how an article enters the DASH repository, we have an express affirmation of the OA policy’s nonexclusive license, providing yet a further satisfaction of the Section 205(e) “written instrument” clause.

Priest mentions another way of strengthening the argument of survival of the nonexclusive license, namely, incorporating the license into faculty employment agreements, either directly or by reference. This provides further backup that the license is individually affirmed through the employment agreement. We take additional steps along these lines at Harvard as well.

One of the most attractive aspects of the default rights retention approach to open-access policies is that the author retains rights automatically, without having to negotiate individually with publishers and regardless of the particularities and exigencies of any later publication agreement, while maintaining complete author choice in the matter through the open license waiver option. It is good to know that a thorough independent legal review of our approach has ratified that understanding.

The inevitability of open access

June 28th, 2012

|

| …wave of the future… “Nonantum Wave” photo by flickr user mjsawyer. Used by permission (CC-BY-NC-ND 2.0). |

I get the sense that we’ve moved into a new phase in discussions of open access. There seems to be a consensus that open access is an inevitability. We’re hearing this not only from the usual suspects in academia but from publishers, policy-makers, and other interested parties. I’ve started collecting pertinent quotes. The voices remarking on the inevitability of open access range from congressional representatives sponsoring the pro-OA FRPAA bill (Representative Lofgren) to the sponsors of the anti-OA RWA bill (Representatives Issa and Maloney), from open-access publishers (Sutton of Co-Action) to the oldest of guard subscription publishers (Campbell of Nature). Herewith, a selection. Pointers to other examples would be greatly appreciated.

“I agree which is why I am a cosponsor of the bill [FRPAA, HR4004], but I think even if the bill does not pass, this [subscription journal] model is dead. It is just a question of how long the patient is going to be on life support.”

— Zoe Lofgren (D-CA), March 29, 2012

“As the costs of publishing continue to be driven down by new technology, we will continue to see a growth in open access publishers. This new and innovative model appears to be the wave of the future.”

“I realise this move to open access presents a challenge and opportunity for your industry, as you have historically received funding by charging for access to a publication. Nevertheless that funding model is surely going to have to change even beyond the welcome transition to open access and hybrid journals that’s already underway. To try to preserve the old model is the wrong battle to fight.”

— David Willetts (MP, Minister of State for Universities and Science), May 2, 2012

“[A] change in the delivery of scientific content and in the business models for delivering scholarly communication was inevitable from the moment journals moved online, even if much of this change is yet to come.”

— Caroline Sutton (Publisher, Co-Action Publishing), December 2011

“My personal belief is that that’s what’s going to happen in the long run.”

— Philip Campbell (Editor-in-chief, Nature), June 8, 2012

“In the longer term, the future lies with open access publishing,” said Finch at the launch of her report on Monday. “The UK should recognise this change, should embrace it and should find ways of managing it in a measured way.”

“Open access is here to stay, and has the support of our key partners.”

— Association of Learned and Professional Society Publishers, July 25, 2011

(Hat tip to Peter Suber for pointers to a couple of these quotes.)

Talmud and the Turing Test

June 16th, 2012

|

| …the Golem… Image of the statue of the Golem of Prague at the entrance to the Jewish Quarter of Prague by flickr user D_P_R. Used by permission (CC-BY 2.0). |

Alan Turing, the patron saint of computer science, was born 100 years ago this week (June 23). I’ll be attending the Turing Centenary Conference at University of Cambridge this week, and am honored to be giving an invited talk on “The Utility of the Turing Test”. The Turing Test was Alan Turing’s proposal for an appropriate criterion to attribute intelligence (that is, capacity for thinking) to a machine: you verify through blinded interactions that the machine has verbal behavior indistinguishable from a person.

In preparation for the talk, I’ve been looking at the early history of the premise behind the Turing Test, that language plays a special role in distinguishing thinking from nonthinking beings. I had thought it was an Enlightenment idea, that until the technological advances of the 16th and 17th centuries, especially clockwork mechanisms, the whole question of thinking machines would never have entertained substantive discussion. As I wrote earlier,

Clockwork automata provided a foundation on which one could imagine a living machine, perhaps even a thinking one. In the midst of the seventeenth-century explosion in mechanical engineering, the issue of the mechanical nature of life and thought is found in the philosophy of Descartes; the existence of sophisticated automata made credible Descartes’s doctrine of the (beast-machine), that animals were machines. His argument for the doctrine incorporated the first indistinguishability test between human and machine, the first Turing test, so to speak.

But I’ve seen occasional claims here and there that there is in fact a Talmudic basis to the Turing Test. Could this be true? Was the Turing Test presaged, not by centuries, but by millennia?

Uniformly, the evidence for Talmudic discussion of the Turing Test is a single quote from Sanhedrin 65b.

Rava said: If the righteous wished, they could create a world, for it is written, “Your iniquities have been a barrier between you and your God.” For Rava created a man and sent him to R. Zeira. The Rabbi spoke to him but he did not answer. Then he said: “You are [coming] from the pietists: Return to your dust.”

Rava creates a Golem, an artificial man, but Rabbi Zeira recognizes it as nonhuman by its lack of language and returns it to the dust from which it was created.

This story certainly describes the use of language to unmask an artificial human. But is it a Turing Test precursor?

It depends on what one thinks are the defining aspects of the Turing Test. I take the central point of the Turing Test to be a criterion for attributing intelligence. The title of Turing’s seminal Mind article is “Computing Machinery and Intelligence”, wherein he addresses the question “Can machines think?”. Crucially, the question is whether the “test” being administered by Rabbi Zeira is testing the Golem for thinking, or for something else.

There is no question that verbal behavior can be used to test for many things that are irrelevant to the issues of the Turing Test. We can go much earlier than the Mishnah to find examples. In Judges 12:5–6 (King James Version)

5 And the Gileadites took the passages of Jordan before the Ephraimites: and it was so, that when those Ephraimites which were escaped said, Let me go over; that the men of Gilead said unto him, Art thou an Ephraimite? If he said, Nay;

6 Then said they unto him, Say now Shibboleth: and he said Sibboleth: for he could not frame to pronounce it right. Then they took him, and slew him at the passages of Jordan: and there fell at that time of the Ephraimites forty and two thousand.

The Gileadites use verbal indistinguishability (of the pronounciation of the original shibboleth) to unmask the Ephraimites. But they aren’t executing a Turing Test. They aren’t testing for thinking but rather for membership in a warring group.

What is Rabbi Zeira testing for? I’m no Talmudic scholar, so I defer to the experts. My understanding is that the Golem’s lack of language indicated not its own deficiency per se, but the deficiency of its creators. The Golem is imperfect in not using language, a sure sign that it was created by pietistic kabbalists who themselves are without sufficient purity.

Talmudic scholars note that the deficiency the Golem exhibits is intrinsically tied to the method by which the Golem is created: language. The kabbalistic incantations that ostensibly vivify the Golem were generated by mathematical combinations of the letters of the Hebrew alphabet. Contemporaneous understanding of the Golem’s lack of speech was connected to this completely formal method of kabbalistic letter magic: “The silent Golem is, prima facie, a foil to the recitations involved in the process of his creation.” (Idel, 1990, pages 264–5) The imperfection demonstrated by the Golem’s lack of language is not its inability to think, but its inability to wield the powers of language manifest in Torah, in prayer, in the creative power of the kabbalist incantations that gave rise to the Golem itself.

Only much later does interpretation start connecting language use in the Golem to soul, that is, to an internal flaw: “However, in the medieval period, the absence of speech is related to what was conceived then to be the highest human faculty: reason according to some writers, or the highest spirit, Neshamah, according to others.” (Idel, 1990, page 266, emphasis added)

By the 17th century, the time was ripe for consideration of whether nonhumans had a rational soul, and how one could tell. Descartes’s observations on the special role of language then serve as the true precursor to the Turing Test. Unlike the sole Talmudic reference, Descartes discusses the connection between language and thinking in detail and in several places — the Discourse on the Method, the Letter to the Marquess of Newcastle — and his followers — Cordemoy, La Mettrie — pick up on it as well. By Turing’s time, it is a natural notion, and one that Turing operationalizes for the first time in his Test.

The test of the Golem in the Sanhedrin story differs from the Turing Test in several ways. There is no discussion that the quality of language use was important (merely its existence), no mention of indistinguishability of language use (but Descartes didn’t either), and certainly no consideration of Turing’s idea of blinded controls. But the real point is that at heart the Golem test was not originally a test for the intelligence of the Golem at all, but of the purity of its creators.

References

Idel, Moshe. 1990. Golem: Jewish magical and mystical traditions on the artificial anthropoid, Albany, N.Y.: State University of New York Press.

More reason to outlaw Impact Factors from personnel discussions

June 14th, 2012

Pity the poor, beleaguered “Impact Factor™” (IF), a secret mathematistic formula originally intended to serve as a proxy for journal quality. No one seems to like it much. The manifold problems with IF have been rehearsed to death:

- The calculation isn’t a proper average.

- The calculation is statistically inappropriate.

- The calculation ignores most of the citation data.

- The calculated values aren’t reproducible.

- Citation rates, and hence Impact Factors, vary considerably across fields making cross-discipline comparison meaningless.

- Citation rates vary across languages. Ditto.

- IF varies over time, and varies differentially for different types of journals.

- IF is manipulable by publishers.

The study by the International Mathematical Union is especially trenchant on these matters, as is Bjorn Brembs’ take. I don’t want to pile on, just look at some new data that shows that IF has been getting even more problematic over time.

One of the most egregious uses of IF is in promotion and tenure discussions. It’s been understood for a long time that the Impact Factor, given its manifest problems as a method for ranking journals, is completely inappropriate for ranking articles. As the European Association of Science Editors has said

Therefore the European Association of Science Editors recommends that journal impact factors are used only – and cautiously – for measuring and comparing the influence of entire journals, but not for the assessment of single papers, and certainly not for the assessment of researchers or research programmes either directly or as a surrogate.

Even Thomson Reuters says

The impact factor should be used with informed peer review. In the case of academic evaluation for tenure it is sometimes inappropriate to use the impact of the source journal to estimate the expected frequency of a recently published article.

“Sometimes inappropriate.” Snort.

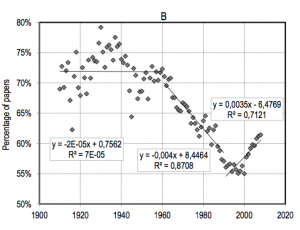

|

| …the money chart… |

Check out the money chart from the recent paper “The weakening relationship between the Impact Factor and papers’ citations in the digital age” by George A. Lozano, Vincent Lariviere, and Yves Gingras.

They address the issue of whether the most highly cited papers tend to appear in the highest Impact Factor journals, and how that has changed over time. One of their analyses looked at the papers that fall in the top 5% for number of citations over a two-year period following publication, and depicts what percentage of these do not appear in the top 5% of journals as ranked by Impact Factor. If Impact Factor were a perfect reflection of the future citation rate of the articles in the journal, this number should be zero.

As it turns out, the percentage has been extremely high over the years. The majority of top papers fall into this group, indicating that restricting attention to top Impact Factor journals doesn’t nearly cover the best papers. This by itself is not too surprising, though it doesn’t bode well for IF.

More interesting is the trajectory of the numbers. At one point, roughly up through World War II, the numbers were in the 70s and 80s. Three quarters of the top-cited papers were not in the top IF journals. After the war, a steady consolidation of journal brands, along with the invention of the formal Impact Factor in the 60s and its increased use, led to a steady decline in the percentage of top articles in non-top journals. Basically, a journal’s imprimatur — and its IF along with it — became a better and better indicator of the quality of the articles it published. (Better, but still not particularly good.)

This process ended around 1990. As electronic distribution of individual articles took over for distribution of articles bundled within printed journal issues, it became less important which journal an article appeared in. Articles more and more lived and died by their own inherent quality rather than by the quality signal inherited from their publishing journal. The pattern in the graph is striking.

The important ramification is that the Impact Factor of a journal is an increasingly poor metric of quality, especially at the top end. And it is likely to get even worse. Electronic distribution of individual articles is only increasing, and as the Impact Factor signal decreases, there is less motivation to publish the best work in high IF journals, compounding the change.

Meanwhile, computer and network technology has brought us to the point where we can develop and use metrics that serve as proxies for quality at the individual article level. We don’t need to rely on journal-level metrics to evaluate articles.

Given all this, promotion and tenure committees should proscribe consideration of journal-level metrics — including Impact Factor — in their deliberations. Instead, if they must use metrics, they should use article-level metrics only, or better yet, read the articles themselves.

Editorial board members: What to ask of your journal

June 11th, 2012

|

| …good behavior… |

Harvard made a big splash recently when my colleagues on the Faculty Advisory Council to the Harvard Library distributed a Memorandum on Journal Pricing. One of the main problems with the memo, however, is the relatively imprecise recommendations that it makes. It exhorts faculty to work with journals and scholarly societies on their publishing and pricing practices, but provides no concrete advice on exactly what to request. What is good behavior?

I just met with a colleague here at Harvard who raised the issue with me directly. He’s a member of the editorial board of a journal and wants to do the right thing and make sure that the journal’s policies make them a good actor. But he doesn’t want to (and shouldn’t be expected to) learn all the ins and outs of the scholarly publishing business, the legalisms of publication agreements and copyright, and the interactions of all that with the policies of the particular journal. He’s not alone; there are many others in the same boat. Maybe you are too. Is there some pithy request you can make of the journal that encapsulates good publishing practices?

(I’m assuming here that converting the journal to open access is off the table. Of course, that would be preferable, but it’s unlikely to get you very far, especially given that the most plausible revenue model for open-access journal publishing, namely, publication fees, is not well supported by the scholarly publishing ecology as of yet.)

There are two kinds of practices that the Harvard memo moots: it explicitly mentions pricing practices of journals, and implicitly brings up author rights issues in its recommendations. Scholar participants in journals (editors editorial board members, reviewers) may want to discuss both kinds of practices with their publishers. I have recommendations for both.

Rights practices

Here’s my candidate recommendation for ensuring a subscription journal has good rights practice. You (and, ideally, your fellow editorial board members) hand the publisher a copy of the Science Commons Delayed Access (SCDA) addendum. (Here’s a sample.) You request that they adjust their standard article publication agreement so as to make the addendum redundant. This request has several nice effects.

- It’s simple, concrete, and unambiguous.

- It describes the desired result in terms of functionality — what the publication agreement should achieve — not how it should be worded.

- It guarantees that the journal exhibits best practices for a subscription journal. Any journal that can satisfy the criterion that the SCDA addendum is redundant:

- Let’s authors retain rights to use and reuse the article in further research and scholarly activities,

- Allows green OA self-archiving without embargo,

- Allows compliance with any funder policies (such as the NIH Public Access Policy),

- Allows compliance with employer policies (such as university open-access policies) without having to get a waiver, and

- Allows distribution of the publisher’s version of the article after a short embargo period.

- It applies to journals of all types. (Just because the addendum comes from Science Commons doesn’t mean it’s not appropriate for non-science journals.)

- It doesn’t require the journal to give up exclusivity to its published content (though it makes that content available with a moving six-month wall).

The most controversial aspect of an SCDA-compliant agreement from the publisher’s point of view is likely the ability to distribute the publisher’s version of the article after a six-month embargo. I wouldn’t be wed to that six month figure. This provision would be the first thing to negotiate, by increasing the embargo length — to one year, two years, even five years. But sticking to some finite embargo period for distributing the publisher’s version is a good idea, if only to serve as precedent for the idea. Once the journal is committed to allowing distribution of the publisher’s version after some period, the particular embargo length might be reduced over time.

Pricing practices

The previous proposal does a good job, to my mind, of encapsulating a criterion of best publication agreement practice, but it doesn’t address the important issue of pricing practice. Indeed, with respect to pricing practices, it’s tricky to define good value. Looking at the brute price of a journal is useless, since journals publish wildly different numbers of articles, from the single digits to the four digits per year, so three orders of magnitude variations in price per journal is expected. Price per article and price per page are more plausible metrics of value, but even there, because journals differ in the quality of articles they tend to publish, hence their likely utility to readers, variation in these metrics should be expected as well. For this reason, some analyses of value look to citation rate as a proxy for quality, leading to a calculation of price per citation.

Another problem is getting appropriate measures of the numerator in these metrics. When calculating price per article or per page or per citation, what price should one use? Institutional list price is a good start. List price for individual subscriptions is more or less irrelevant, given that individual subscriptions account for a small fraction of revenue. But publishers, especially major commercial publishers with large journal portfolios, practice bundling and price discrimination that make it hard to get a sense of the actual price that libraries pay. On the other hand, list price is certainly an upper bound on the actual price, so not an unreasonable proxy.

Finally, any of these metrics may vary systematically across research fields, so the metrics ought to be relativized within a field.

Ted and Carl Bergstrom have collected just this kind of data for a large range of journals at their journalprices.com site, calculating price per article and price per citation along with a composite index calculated as the geometric mean of the two. To handle the problem of field differences, they provide a relative price index (RPI) that compares the composite to the median for non-profit journals within the field, and propose that a journal be considered “good value” if RPI is less than 1.25, “medium value” if its RPI is less than 2, and “bad value” otherwise.

As a good first cut at a simple message to a journal publisher then, you could request that the price of a journal be reduced to bring its RPI below 1.25 (that is, good value), or at least 2 (medium value). Since lots of journals run in the black with composite price indexes below median, that is, with RPI below 1, achieving an RPI of 2 should be achievable for an efficient publisher. (My colleague’s journal, the one that precipitated this post, has an RPI of 2.85. Plenty of room for improvement.)

In summary, you ask the journal to change its publication agreement to be SCDA-compliant and its price to have RPI less than 2. That’s specific, pragmatic, and actionable. If the journal won’t comply, you at least know where they stand. If you don’t like the answers you’re getting, you can work to find a new publisher willing to play ball, or at least, don’t lend your free labor to the current one.

Processing special collections: An archivist’s workstation

May 29th, 2012

|

| John Tenniel, c. 1864. Study for illustration to Alice’s adventures in wonderland. Harcourt Amory collection of Lewis Carroll, Houghton Library, Harvard University. |

We’ve just completed spring semester during which I taught a system design course jointly in Engineering Sciences and Computer Science. The aim of ES96/CS96 is to help the students learn about the process of solving complex, real-world problems — applying engineering and computational design skills — by undertaking an extended, focused effort directed toward an open-ended problem defined by an interested “client”.

The students work independently as a self-directed team. The instructional staff provides coaching, but the students do all of the organization and carrying out of the work, from fact-finding to design to development to presentation of their findings.

This term the problem to be addressed concerned the Harvard Library’s exceptional special collections, vast holdings of rare books, archives, manuscripts, personal documents, and other materials that the library stewards. Harvard’s special collections are unique and invaluable, but are useful only insofar as potential users of the material can find and gain access to them. Despite herculean efforts of an outstanding staff of archivists, the scope of the collections means that large portions are not catalogued, or catalogued in insufficient detail, making materials essentially unavailable for research. And this problem is growing as the cataloging backlog mounts. The students were asked to address core questions about this valuable resource: What accounts for this problem at its core? Can tools from computer science and technology help address the problems? Can they even qualitatively improve the utility of the special collections?

The students’ recommendations centered around the design, development, and prototyping of an “archivist’s workstation” and the unconventional “flipped” collections processing that the workstation enabled. Their process involves exhaustive but lightweight digitization of a collection as a precursor to highly efficient metadata acquisition on top of the digitized images, rather than the conventional approach of digitizing selectively only after all processing of the collection is performed. The “digitize first” approach means that documents need only be touched once, with all of the sorting, arrangement, and metadata application being performed virtually using optimized user interfaces that they designed for these purposes. The output is a dynamic finding aid with images of all documents, complete with search and faceted browsing of the collection, to supplement the static finding aid of traditional archival processing. The students estimate that processing in this way would be faster than current methods, while delivering a superior result. Their demo video (below) gives a nice overview of the idea.

The deliverables for the course are now available at the course web site, including the final report and a videotape of their final presentation before dozens of Harvard archivists, librarians, and other members of the community.

I hope others find the ideas that the students developed as provocative and exciting as I do. I’m continuing to work with some of them over the summer and perhaps beyond, so comments are greatly appreciated.

Open letter on the Access2Research White House petition

May 21st, 2012

I just sent the email below to my friends and family. Feel free to send a similar letter to yours.

You know me. I don’t send around chain letters, much less start them. So you know that if I’m sending you an email and asking you to tell your friends, it must be important.

This is important.

As taxpayers, we deserve access to the research that we fund. It’s in everyone’s interest: citizens, researchers, government, everyone. I’ve been working on this issue for years. I recently testified before a House committee about it.

Now we have an opportunity to tell the White House that they need to take action. There is a petition at the White House petition site calling for “President Obama to act now to implement open access policies for all federal agencies that fund scientific research.” If we get 25,000 signatures by June 19, 2012, the petition will be placed in the Executive Office of the President for a policy response.

Please sign the petition. I did. I was signatory number 442. Only 24,558 more to go.

Signing the petition is easy. You register at the White House web site verifying your email address, and then click a button. It’ll take five minutes tops. (If you’re already registered, you’re down to ten seconds.)

Please sign the petition, and then tell those of your friends and family who might be interested to do so as well. You can inform people by tweeting them this URL <http://bit.ly/MAbTHG> or posting on your Facebook page or sending them an email or forwarding them this one. If you want, you can point them to a copy of this email that I’ve put up on the web at <http://bit.ly/J8EmyD>.

Since I’ve just requested that you send other people this email (and that they do so as well), I want to make sure that there’s a chain letter disclaimer here: Do not merely spam every email address you can find. Please forward only to those people who you know well enough that it will be appreciated. Do not forward this email after June 19, 2012. The petition drive will be over by then. By all means before forwarding the email check the White House web link showing the petition at whitehouse.gov to verify that this isn’t a hoax. Feel free to modify this letter when you forward it, but please don’t drop the substance of this disclaimer paragraph.

You can find out more about the petition from the wonderful people at Access2Research who initiated it, and you can read more about my own views on open access to the scholarly literature at my blog, the Occasional Pamphlet.

Thank you for your help.

Stuart M. Shieber

Welch Professor of Computer Science

Director, Office for Scholarly Communication

Harvard University