Week 5 Response: Yin, Yang, Yazid

The 10th of Muharram is perhaps the most consequential date in Shia Islam. The Battle of Karbala marks the fight of not just the martyrdom of the grandson of the Prophet, Hossein, at the hands of the Ummayid Caliph Yazid and his troops, but also the fight of truth against falsehood, justice against oppression, and good against evil. I present this duality in a collage using yin and yang – yin, the dark, as Yazid, and yang, the light, as Hossein.

The Battle of Karbala is particularly useful for political ends, especially in Iran. First, the readings this week stressed that Hossein’s martyrdom is so vivid in the Shiite imagination that it persists today in the ta’ziyeh, a “passion play,” and is an immediately recognizable and powerful reference in every corner of Iran — rural villages included. Second, the duality of good versus evil can be, and sometimes is, easily manipulated to represent the persecution of Iran by its enemies. Iranians first used this imagery in the Iranian Revolution by equating the deposed Shah and America with Yazid; in the Iran-Iraq War, by comparing Iranian troops with Hossein’s troops at Karbala; and America once again with Yazid during heightened sanctions and nuclear negotiations. The Chelkowski reading this week mentioned these modern references to the West during the taziyeh, including the use of sunglasses or British clothing on Yazid or his troops.

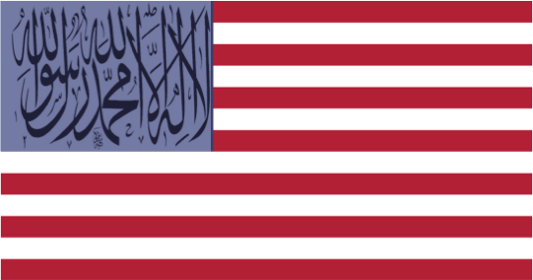

In my collage, Yazid’s half of the image is red, and his advancing troops are in the background. To demonstrate the use of the Battle of Karbala in Iranian politics, the large image of Yazid himself was taken from a recent billboard in Tehran showing him side-by-side with Barack Obama. The smaller image near the corner is of Uncle Sam draped in Yazid’s traditional clothing; the original image, a poster also from Iran, said marg bar yazid, marg bar amrika – death to Yazid, death to America. In contrast, Hossein’s half of the image is green, and the background is a famous painting depicting women mourning over Imam Hossein’s horse after his martyrdom. Hossein himself stands facing Yazid with an arrow in his chest, prepared to die resisting tyranny.