Week 11 Response: Veil Politics

A major theme in this week’s readings and especially in lecture was the politicization of women’s clothing. Women often become “objects” of reform during colonial projects and national revolutions, with veiling and unveiling seen as the ultimate symbols of either acceptance of (or resistance to) Westernization. As an extension of this theme, I wanted to show in this week’s art project how women have been seen as “the battleground for ideological warfare,” as Professor Asani said in lecture, between competing visions of Islam and modernity.

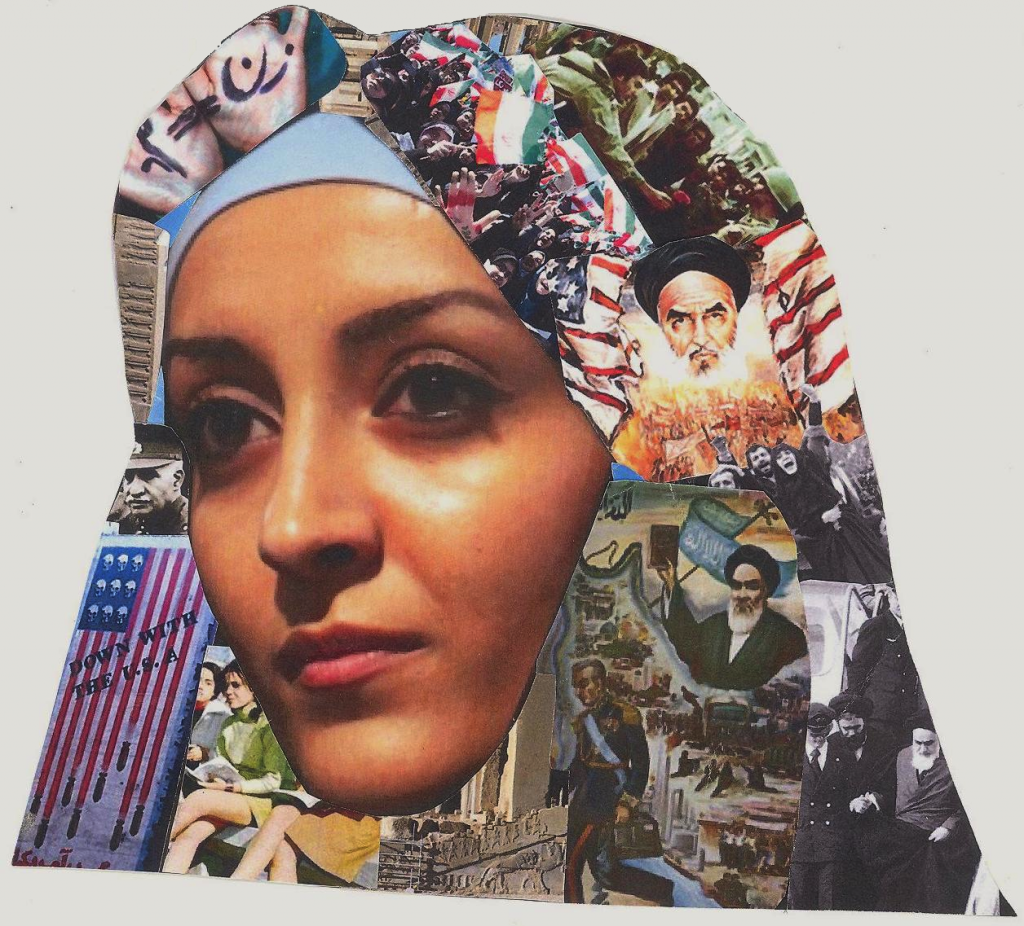

I began with a picture of an Iranian woman wearing a chador. As we covered this week in the readings and in lecture, Iranian women were forced to cover their hair after the 1979 Islamic Revolution (Buchman 91). Although they were not required to wear the full chador, women in state-produced art (such as the propaganda art in pages 137-138 in the Chelkowski reading) were all depicted wearing the chador. Buchman himself points to the increasingly lax regulations in the Islamic Republic by saying that women veil less strictly than they did in the first years of the Revolution (95). Buchman, like so many others, measures the political values of a country by the veil’s popularity — or lack thereof. The decision to wear the chador, or any time of “Islamic” dress, is robbed of its personal significance and becomes a political act.

To reflect this pervasive tendency to politicize women’s clothing, I made a collage of important moments or art in modern Iranian history within the woman’s chador. I included the famous posters from the Chelkowski reading — one depicting the downfall of the Shah and victory of Khomeini and the Islamic Republic, and the other showing Khomeini’s face between a torn American flag, symbolizing the end of a perceived puppet government and victory of the Islamic Revolution. Other images in this collage are rife with political meaning — the ruins of Persepolis, Reza Shah, unveiling women in skirts, Iranians waving the flag of the Islamic Republic, a famous photograph of a protestor during the Islamic Revolution handing a soldier a rose, and a woman’s hands with زن = مرد (woman = man) written in black.

While I used a picture of an Iranian woman and pictures from Iranian history to fill her chador, this trend of politicization of women’s clothing is far from limited to Iran. Across most Middle Eastern states, a common response to the top-down imposition of “Western” constructions of identity on Muslim societies (through colonization or through the decrees of a “Westernized” dictator) was a return to visible markers of Islam — a beard for men, conservative clothing for women. All of these images underscore the point that women’s clothing is politicized to the point that it is often interpreted as the victory of one ideology (political Islam) over another (secular modernization, or Westernization), or vice versa.