Prologue

May 8th, 2014 at 2:22 pm (Uncategorized)

At the beginning of the semester, Professor Asani described today’s environment as a world where people from different backgrounds are in closer contact with one another than they have ever been before. However, rather than this proximity resulting in a better understanding of different cultures and beliefs, it has led to greater misperceptions and the perpetuation of stereotypes. He said rather than calling this a “clash of civilizations,” he prefers to call it “the clash of ignorances”. For the Love of God and His Prophet uses the cultural studies approach to study the world’s Muslim communities. Most religion courses focus on teaching through doctrines, theologies and philosophies, neglecting the importance of arts and literature. This course, however, puts the emphasis on these literary and artistic dimensions, allowing students to experience and discover Islam for themselves, prior to delving into the doctrines and theologies.

Professor Asani began the semester by encouraging students to abandon their preconceived notions of Islam and Muslim identity. We are often presented with stereotypical images of Muslims – Arab, bearded, hijabi, terrorist – the list goes on and on. We are told that Islam says this and does that. However, Islam is a religion; it does not say or do anything. It is people who say and do things. This is a fact that is often forgotten or overlooked in modern culture. We are so often presented with a single, static image of Islam and Muslims that we have forgotten that just as there is not one way to be Christian, Jewish, Hindu, Buddhist, Atheist, etc, there is not one way to be Muslim.

As evidenced by the intricate calligraphic designs in Islamic architecture, writing holds a special place in Islam. Many consider the act of writing Qur’anic verses a form of worship; those who are especially gifted in the art of calligraphy are known as “scribe angels”. However, equally important is the idea of the Qur’an as an aural and oral text – something to be “listened to with the ear and experienced with the heart”. Originally, the Qur’an, the literal translation being “recitation,” was solely an aural text, revealed to Prophet Muhammad by the angel Gabriel and then recited to the community. It was not until long after the Prophet’s death that the Qur’an was put into writing.

Qur’anic recitation is so revered in the Islamic community that there exists a set of rules governing its pronunciation and rhythm known as tajweed. Reciting and listening to the Qur’an are considered a form of communion with Allah. As seen in the film “Koran by Heart,” Qur’anic recitation competitions are held across the globe with the most renowned event held annually in Egypt. Often times the competitors, some as young as seven years old, are able to recite the Qur’an in its entirety without being able to read or speak Arabic. Someone who has memorized the Qur’an is known as hafiz al-Qur’an, “Guardian of the Qur’an,” and is considered to have been especially blessed by Allah.

In addition to poetry and Qur’anic recitation, other forms of artistic expression are used to observe important events in Islamic history. One of these expressions is the ta’ziyeh, a passion play originating in Iran that re-enacts the Battle of Karbala. The Battle of Karbala and the subsequent martyrdom of Hussein, the son of Ali and the grandson of Muhammad, is one of the most important events in Shi’a Islam. The first month of the Islamic calendar, Muharram, marks an important time of commemoration and mourning for Hussein. The most important day of Muharram is known as Ashura when Umayyad caliph Yazid beheaded Hussein and killed most of his family. Ta’ziyeh is unique in how performers are able to evoke raw emotion from the audience, regardless of the number of times the play has been seen and despite the fact that the audience is aware of its ending.

The principle reason for these strong emotions is that Shi’ite Muslims consider Hussein to be part of Ahl al-Bayt and therefore the rightful successor of Muhammad after Ali. From the Shi’ite perspective, the Battle of Karbala was the prototypical conflict between good and evil, with Hussein representing good and Yazid evil. It is their belief that all those who are pious and righteous suffer in this world, as suffering is ultimately redemptive and leads to salvation in the afterlife – a notion reflected in many other religions (consider the story of Jesus).

In discussing the importance of the Battle of Karbala, Professor Asani noted, “Sunni theology developed in the context of historical triumph and Shi’i in the context of worldly defeat”. However, while these two sects may have differing theological beliefs and religious practices, they are both part of the same religion and followers of Allah.

During ta’ziyeh, the performers can sometimes slip into a trance. This departure from worldly reality is similar to the mystical experience of Sufism. One of the more notable forms of mysticism is practiced by the Mevlevi order also known as the Whirling Dervishes. The order was founded by the followers of the famous 13th century poet Rumi and gained notoriety for its practice of stationary spinning as a means of dhikr, literally meaning remembrance of God. Whirling is representative of how the planets turn around the sun and is a way of abandoning the nafs or ego. This is a central concern of Sufi rituals as the dervishes attempt to revive memories of their “real” identity. It is the belief of Sufis that humans are “in the sleep of negligence and have forgotten their true identity” and their souls “yearn to return to the primordial state of union with God”.

These practices have been increasingly challenged by the secularization of states and the commercialization of “exotic” religions. In Turkey, for example, under Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, public displays of religion were outlawed except for tourism purposes. However, this is in direct contrast to the belief that Sufi song and dance should be reserved for those “mystical elites who are capable of understanding spiritually the powerful emotional message of love poetry put to music”. How is it that these dervishes are able to reconcile the original intentions of whirling with its current purpose? A broader question asks if Islam as a whole is compatible with modernity?

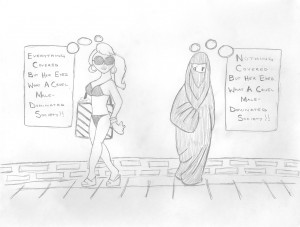

The main subjects that arise when talking about Islam and modernity are women and Western society. In relation to women, the most obvious controversial topic is Islamic dress and the hijab/burqa. There is an obvious clash between Western and Islamic views on feminism and women’s rights and the veil has found itself at the center of the debate. Many Westerners view it as a physical manifestation of oppression and gender inequality. They see veiled woman as being imprisoned in a “walking cell,” even their style of dress controlled by men. On the other hand, the veil is also touted as a liberalization from societal pressures and perhaps most importantly, a choice.

In recent years, the veil has come under attack by governments around the world. Most recently in France in 2011, “le voile intégral”, referring to the burqa and niqab, was cited as a violation of the country’s laïcité and banned in all public places. The law received expansive media coverage as both a law of protection and a law of discrimination, explicitly targeting France’s Muslim population. Is it more important to uphold freedom from religion or freedom of religion? Can the suppression of one liberty be justified as a defense of another?

After the law’s passing, there was in fact an increase in women wearing various styles of veils. Many saw the law as a “Western assault on Islamic values”. The veil has a long history; originally a mark of status in many Mediterranean cultures, it was anything but a sign of oppression. Understanding its cultural context and complex past is crucial to the ongoing debate.

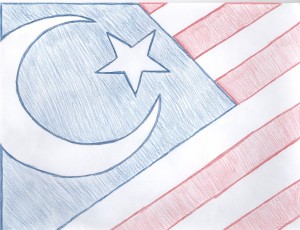

Lastly, it is impossible to discuss Islam in the West without mentioning the attacks of September 11th, 2001. There was certainly tension between Muslims and their Western counterparts prior to the attacks, but this was exceedingly exacerbated in the aftermath. The attempt of Muslims in the West and particularly in the United States to reconcile their dual identities is very prevalent in the arts. We witness the emergence of Islamic hip-hop, “mipsters” (Muslim hipsters), and Western style mosques. However, despite this attempted reconciliation many challenges prevail. In the documentary film New Muslim Cool, Hamza Perez, a Puerto Rican rap artist chooses to leave his drug dealing past behind and converts to Islam. The film highlights both his use of hip-hop to spread Islam to other youths and the hostile environment for Muslims in the post-9/11 era.

This “clash” of identities is again portrayed in the novel The Reluctant Fundamentalist by Mohsin Hamid. The novel tells the story of Changez and his struggle reconciling his dual identity in the aftermath of the September 11th attacks. On the one hand, he is a Princeton graduate with a job at a prestigious firm and a British accent. On the other, he is Muslim, born and raised in Pakistan where his family still remains. At the novel’s beginning, there is no conflict between these identities and Changez is free to move between the two worlds with ease. He is cognizant of the difference between him and his colleagues, but it has no direct impact on daily routine.

All this changes after the September 11th attacks when increased wariness of the “other” results in Changez being harassed on the streets, detained in airports, and ostracized at work. Rejected by his adopted homeland, Changez turns to the only thing he has left – his Pakistani Muslim identity. As the novel’s title suggests, it is not that Changez wanted to be a fundamentalist, he was quite content with his life as both a privileged American and a Pakistani Muslim, but that he was forced to become one. Even the type of “fundamentalist” that Changez becomes is very different from the fundamentalist that one typically envisions.

Through its focus on the arts and literature, For the Love of God and His Prophet provides an in-depth look at Islam and Muslim culture not possible in the traditional, philosophical study of religion. By presenting students with tangible, artistic expressions of religion, Professor Asani allows them to truly experience the multi-dimensional aspects of Islam as it has evolved across regions and time.