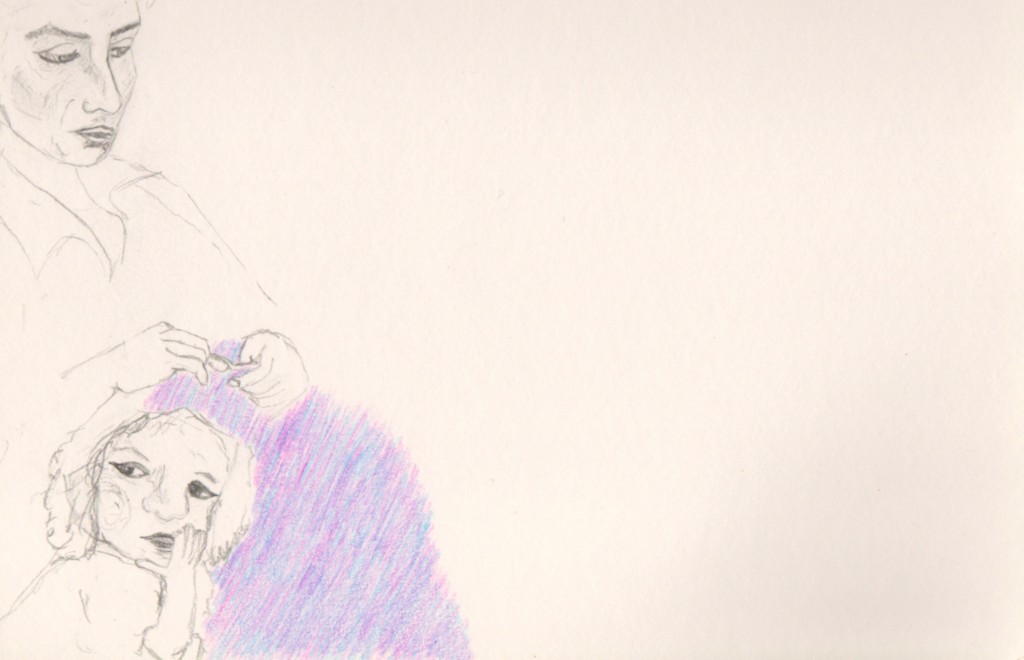

This piece was inspired by our lectures and readings this week on contemporary Islam, especially with the focus on how social, political, and religious energies and conflicts play out on the body of the woman. A key point in the readings – particularly Weber’s “Unveiling Scheherazade: Feminist Orientalism in the International Alliance of Women, 1911-1950” – seemed to me encapsulated in lecture when Professor Asani referred to “Women as the battleground for ideological warfare between competing visions of Islam”. What was interesting to me was the extent to which these “competing visions” belong to men and belong to women. The traditional conception of female oppression is that men are the oppressors and women the voiceless, which may be true to an extent but is complicated through the angle Weber adopts, exploring how women themselves viewed the role of women, and through the quotes shared by Professor Asani, many of which came from women (and going a step further than Weber, Islamic women), and through the documentary clip we saw investigating Turkey’s ban on the veil, airing the views of women who believe in and don’t believe in donning the veil.

Therefore, in this piece, I depict a woman sewing what might be taken to be a hijab. For me, this addresses and presses the question of what Muslim women want for themselves and their fellow woman, and the question of their role in shaping society and society’s treatment of women. This draws on Shirin Ebadi’s sentiment, shared in lecture, “The humiliation inflicted on women is the result of a diseased gene that is passed on to every generation of men, not only by society as a whole but also by their mothers. It is mothers who raise boys who become men. It is up to mothers to pass on that diseased gene…” My focus here is not on the “humiliation” or the “diseased gene” but on the participation of women in shaping and influencing women’s roles and men’s attitudes towards women. The child rests against her mother’s lap as a representation of the object of these cultural, political, and social forces, someone who will or will not wear a hijab, someone who will or will not have the power to make that choice. The unfinished lines and feel of the entire piece, and the fact that the hijab has not quite taken shape, hopefully lend to that sense of ambiguity and lack of resolution, wherein the ‘question’ I claim to pose remains unanswered, remains open to interpretation and further questioning, perhaps even dialogue and discussion. The great empty spaces of the piece are thus filled with all that is as yet unsaid.

Post a Comment