Entries from February 2021

February 27th, 2021 · 7 Comments

[Kara]

Less than a week after being kicked out of my college dorm and moving back home, there I stood in the middle of my childhood room—a disheveled, half-painted (both the walls and, due to my frantic painting style, myself) mess as I tried to prepare my personal space for what seemed to be a stay-at-home order with an undetermined end. As I took a needed break from painting some time past midnight, I grabbed my phone to look at the most recent news of a disease still new to me. The New York Times had reported an estimated 4,043 new cases of the Coronavirus and 50 new deaths on that day, March 19th (New York Times). I fell onto my bed in the middle of my room and began reading the stories of those families who lost their loved ones so unexpectedly. As I read, I began to feel the pain of their stories, the fear of the workers who sacrificed their own health to try to save them, and the hopelessness of all the others like me who were reading that the “darkest days of the disease are ahead.” Needless to say, I felt utterly defeated beyond myself.

Nearly a year later and the United States has seen over half a million total deaths and days where the number of daily new cases have reached well above 300,000. However, as the updates came with skyrocketing numbers and increasing rates, I no longer felt defeated the same way that I had in mid-March. The numbers became normal, and I began to wonder—how could I, along with everyone else digesting new tragedy in a constantly changing pandemic, have had such a dramatic change in heart?

The collapse of compassion is the decrease in empathetic response that we experience as the number of people suffering increases. Some studies have supported the hypothesis that this decrease in affect plateaus as the number of individuals increases, creating a “psychological numbing” effect (Fetherstonhaugh, Sandlovic, Johnson, and Friedrich, 1997), while others have argued that the decrease in affect continues to decrease as the number of suffering individuals increases. In the case of the pandemic, it seems the latter is more aligned with my personal experience—a “dehumanization” possibly due to the costliness of mentally-draining empathy in a pandemic that has now persisted for a year (Cameron, Harris, & Payne, 2015).

The sources of compassion collapse, however, are debated. Theory about the conceptual representation of groups tends to support a “tragedy versus statistic” mentality; individuals require more attention put into perspective taking and therefore more effectively trigger an affective response compared to groups (Hamilton and Sherman, 1996). However, in a study conducted by Cameron and Payne (2011), experiments found initial evidence supporting an alternative theory that compassion collapse is driven by motivated emotion regulation, such as a motive to prevent the experience of overwhelming levels of emotion.

A shared theme between these hypotheses seems to be that the costliness of empathy—whether it be in the processing of perspectives or in the emotion-sharing capacity it requires—moderates our ability to empathize with large numbers of people. Recognizing our own collapse of compassion in a pandemic makes us, ironically, recognize the emotionally incomprehensible amount of suffering our society has undergone. Recognition of our limitations to empathize may in turn provide forgiveness for ourselves in navigating the collective long-term effects of an emotionally draining and traumatic year.

[Tyler]

I used to watch the news obsessively in March and April and feel terribly for the people who were getting infected and dying from COVID-19 and for the healthcare workers who were risking their lives taking care of them. It was heartbreaking to hear the updates, but I felt like it was the only possible response. How could I be happy in a time like this? As the months went on, I got numb to the news and felt exhausted just thinking about COVID. Since then, I have been experiencing what many people call pandemic fatigue. Empathy involves both the ability to understand another’s thoughts, feelings and perspective as well as sharing in the emotions of others (de Waal, 2008). One of the many reasons for fatigue is the difficulty of sharing in the feelings of another person let alone the over 500,000 people we have lost and so many more who have suffered in ways both big and small.

Although empathy can be overwhelming, it can lead to prosocial behaviors such as cooperation and altruism (de Waal, 2008). As we have all witnessed over the past year, cooperation is an essential component of getting through an infectious pandemic. Cooperation is needed to follow the health guidelines that keep everyone safe. Cooperation is needed to form mutual aid groups to assist people struggling. It makes sense, then, that empathy might impact the way a group of people or an entire country responds to a pandemic. We have also seen over the past year that different countries have responded differently in the face of this pandemic. Could differences in empathy play a role in explaining the differences in people’s willingness to cooperate for the greater good?

Aival-Naveh, Rothschild-Yakar, and Kurman (2019) did a review of literature that analyzes empathy differences across cultures. The studies divided cultures into either collectivistic, more concerned with others than the self, or individualistic, more concerned with the self than others. By pure definition, it seems that collectivistic cultures would be more empathetic, but the results were more complicated than that. Several brain imaging studies where participants were exposed to the physical and social pain of others supported the finding that collectivistic cultures have higher empathy (Aival-Naveh, Rothschild-Yakar, and Kurman, 2019). Additionally, studies that looked at cognitive empathy or perspective taking consistently found that participants from collectivistic countries were better able to consider another’s perspective than participants from individualistic countries (Aival-Naveh, Rothschild-Yakar, and Kurman, 2019).

One study conducted across 63 countries supported these findings and found that countries with higher empathy also had higher levels of collectivism (Chopik, O’Brien, and Konrath, 2017). However, these data were self-reported, which calls into question the reliability of the empathy rating. It’s possible that people from collectivistic countries see themselves as more empathetic and thus rate themselves as more empathetic. Furthermore, other self-reported surveys found the opposite: that people from individualistic countries had higher empathy than people from collectivist countries (Aival-Naveh, Rothschild-Yakar, and Kurman, 2019). The results are far from definitive but intriguing nonetheless. Future research might directly compare individual countries’ pandemic numbers with their ability to empathize.

Even with its limitations considered, empathy can be an incredibly powerful tool for navigating the pandemic. Understanding our ability to empathize with a group is an integral part of a pandemic that has affected everyone, and acknowledging our limits can help us know not to give up even when the costs of empathy become overwhelming.

References

Aival-Naveh E., Rothschild‐ Yakar L., Kurman J. (2019). Keeping culture in mind: A systematic review and initial conceptualization of mentalizing from a cross‐cultural perspective. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 26(4), 1-25. https://doi. org/10.1111/cpsp.12300

Cameron, C. D., & Payne, B. K. (2011). Escaping affect: How motivated emotion regulation creates insensitivity to mass suffering. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021643

Chopik, W. J., O’Brien, E., Konrath, S. H. (2017). Differences in Empathic Concern and Perspective Taking Across 63 Countries. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 48(1), 23-28. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022116673910

Coronavirus in the US: Latest Map and Case Count. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/us/coronavirus-us-cases.html

De Waal, F. B. M. (2008). Putting the Altruism Back Into Altruism: The Evolution of Empathy. Annual Review of Psychology, 59, 279-300.

Fetherstonhaugh, D., Slovic, P., Johnson, S. M., & Friedrich, J. (1997). Insensitivity to the value of human life: A study of psychophysical numbing. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 14, 283-300.

Hamilton, D. L., and Sherman, S. J. (1996). Perceiving persons and groups. Psychological Review, 103, 336-355.

Tags: Uncategorized

February 26th, 2021 · 4 Comments

[Lara]

“And I just can’t imagine how you could be so okay now that I’m gone

Guess you didn’t mean what you wrote in that song about me

‘Cause you said forever, now I drive alone past your street” (Rodrigo, 2021, 1:25).

I’ve been obsessed with this song ever since it went viral on TikTok. But who isn’t? Who could not empathize with Olivia Rodrigo, take her perspective, or imagine how this relates to one’s own breakup(s)? That’s empathy at work: it operates when we share another’s emotions, mentalize, and monitor the origin of the other’s feelings and their situation (Perry, 2021). Observing another’s emotional state somewhat automatically causes us to activate similar brain regions like the insula and anterior cingulate cortex, therefore, in a sense, ‘match their energy.’ This intrinsic matching promotes altruistic behavior, which is rewarding in that it gives us an emotional stake in another’s well-being through the empathetic gesture (de Waal, 2008). So, empathy is crucial to “feel for” Olivia in this heartfelt breakup song and – more importantly – to maintain close relationships that are emotionally satisfying and healthy in our own lives.

Empathy gives us the chance to quickly connect and relate to others, which we need for coordination and cooperation in our social lives (de Waal, 2008). In building and maintaining intimate relationships, empathy is a “vital emotional force” that is, however, not always automatic (Zaki, 2014). We must tune into our significant others’ love languages and unique perspective to understand their emotional experience and expression.

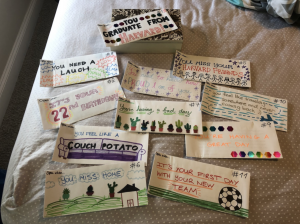

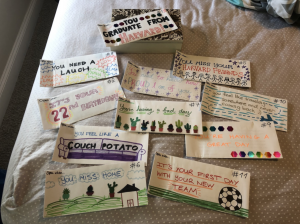

From my personal repertoire, I can report back that it takes a long time to comprehend complex combos of words of affirmation, quality time, and gift giving to fully understand them. Here’s a great example of how you can go above and beyond to make sure that someone knows that you feel with/for them; open when letters were a great way for me to find the correct words and emotional state to match the feelings and needs of someone close to me, even from a distance (I wrote 18 in total, a little excessive):

Open when letters offer a pathway to express that you are tuned into another’s feelings. Such acts not only require empathy but also psychological factors like theory of mind and a lack of egocentrism (Zaki & Cikara, 2015). And so, we’ve learned that empathy can help us improve our own physiological state by engaging in prosocial behaviors, but also brighten someone else’s day and build a stronger connection.

Empathy is also needed during conflict situations and breakups, such as in Olivia’s hit-song and viral TikTok conversation-starter. In conflict-reduction interventions, the focus is on remedying empathic failures by encouraging adults and children to care about others’ feelings and respect diverging views (Zaki & Cikara, 2015). When we regulate our own emotional responses and truly put our differences aside, it can make it easier to rationalize someone else’s views and behaviors. Through teaching specific techniques, learning from those around us, and engaging in perspective-taking throughout development and later in life, it might be possible for that breakup song to hurt less and to, eventually, be okay now that the other person is gone.

[Yufeng]

In the classic sitcom The Big Bang Theory, besides our constant laughter, we may wonder how people can grow up with such different empathy abilities! While Penny can always infer correctly about others’ feelings and react sympathetically, those four super intelligent but socially awkward ‘nerds’ can hardly figure out what on earth is in girls’ heads. Even among the four, the differences are also significant, for Sheldon frequently finds it very hard to even predict his friends’ feelings.

However, these things are not coincidences, or designed for the plots. Instead, it often happens in our life too. For instance, we sometimes want to share our feelings with someone we care about. Then, unfortunately, instead of giving proper responses, they continuously misunderstand our situation. If we cannot get a sense of understanding or acceptance from a friend, we can simply reduce the interaction with him. However, what if this happens in our family? It can certainly cause lots of imbalances.

This brings me the question of what on earth causes the differences and how we can make up for it.

First, it’s attributed to inborn human brain structure. Empathy can be divided into two categories: cognitive empathy, the ability to understand how a person feels and what they might be thinking; affective empathy (emotional empathy), the ability to share the feelings of another person(Davis, 1980). Emotional empathy is supported by regions related to self-other mirroring and affective processing, such as the anterior cingulate cortex, insula, somatosensory cortex, and inferior frontal gyrus, whereas cognitive empathy is supported by regions related to mentalizing and projecting, such as the medial prefrontal cortex, temporoparietal junction, and temporal pole (Abramson, Uzefovsky, Toccaceli, & Knafo-Noam, 2020) (a more vivid illustration can be found in https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7-Q_qU46YAI). It was found that individual differences in affective empathic abilities oriented towards another person were negatively correlated with grey matter volume in the precuneus, inferior frontal gyrus, and anterior cingulate (Banissy, Kanai, Walsh, & Rees, 2012). Additionally, cognitive empathy is shown to be reduced with age, which has been partially proved to be related to reduced brain activity in the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex(Beadle & de la Vega, 2019). Additionally, candidate gene studies have found, for example, that genes that encode for receptors of oxytocin and vasopressin have different associations with measures of emotional and cognitive empathy (Abramson et al., 2020), though some contradictions can be found among these studies.

On top of that, environmental factors also play a role during the empathy formation and development. For instance, exposure to norms of emotional schemas or cultural beliefs about emotions can influence individuals’ emotional experiences. These factors of shared environment include domestic teaching behaviors, social media (Schapira, Anger Elfenbein, Amichay-Setter, Zahn-Waxler, & Knafo-Noam, 2019), specific trainings (Han & Pappas, 2018) etc. By using twin studies, it was found that environment contribute more to cognitive empathy (Abramson et al., 2020), for emotional empathy is derived largely from heritable temperament traits, such as emotional reactivity, regulation, and approach(Davis, Luce, & Kraus, 1994), while cognitive empathy develops more slowly and therefore relies more strongly on learning experiences and growing exposure to cultural nuances (Abramson et al., 2020).

Backing to The Big Bang Theory, we can possibly deduce that Sheldon’s low empathy might mostly result from his genetic background, though surrounded with such a loving family, while Leonard’s higher but still incomplete empathy might mostly result from his mother’s abnormal parenting methods. However, do not be so disappointed when you are born with low empathy, because your acquired training and lifestyle do play an equally great role in your empathic ability. You can get a clue directly from Sheldon’s example that, influenced by his intimate friends and Amy, Sheldon did grow a lot especially in his empathetic aspects.

[Tess]

Okay so we’ve learned a bit about love languages, breakups, and how empathic tendencies can change depending on your environment and upbringing, but is the amount of empathy we feel related to our own emotions? As we discussed in class, this idea of an “emotional battery” somewhat like a social battery kept popping up. If we are more emotionally distressed do we show less empathy to others? Do we have a limit on how much empathy we can feel?

On first thought, my answer would be yes. We’ve all been there– you’re having a bummer day. Your coffee was cold, you got rejected from a job, and you just got off an emotionally draining phone call with your sibling. Nothing seems to be going your way, and you feel like you simply cannot handle one more thing. But can we? Does being in a worse mood actually make us more empathetic?

The empathy amplification hypothesis predicts that positive emotion would be associated with greater empathy while the empathy attenuation hypothesis predicts the opposite; that positive emotion would be associated with lower empathy (Delvin et al. 2014). There seems to be a possibility in both hypotheses: it has been shown that positive emotions are linked to a broader thought-action repertoire that leads to building social resources, and increased positive emotions can increase helping others (Fredrickson, 1998). As Lara mentioned, empathy is a way to quickly connect with others and build our social relationships. However, on the flip side, it has been shown that theory-of-mind use was increased and facilitated by sadness as compared to happiness (Converse et al. 2008). This shows that when we feel happiness, we might actually be less likely to practice empathy (which requires theory-of-mind in being able to identify someone else’s mental state) than when we feel sad.

Okay so which is it? Do negative emotions and sadness lead to less empathy or actually more? Delvin et al. found two interesting conclusions: one, that trait positive emotions (the tendency to experience positive emotions) was associated with lower levels of empathy towards someone experiencing negative emotions, and two, that trait positive emotion participants were more likely to detect increases in mood of others. Boiling this down shows that there might be a relationship between empathy and your current emotional state– if you are happy, empathizing with others who are happy could be easier than empathizing with others who are sad and vice versa. This seems to be the only study of its kind, so I do warn against taking it as the end all be all, but an interesting hypothesis to look deeper into. It does seem to make sense– if we are more to empathize with people similar to us, then it should make sense that empathy would be easier with emotionally similar others. When my roommate comes home in a great mood, I notice myself becoming instantly more happy — empathy impacts us all the time!

One one hand, it may be easier for us to empathize with people who are feeling similar emotions to us, but it is possible for continued exposure to and use of empathy inducing situations can take a toll on our empathy battery. But on the other side of that, as Lara and Yufeng discussed, there are so many incredibly positive benefits to empathy. From forming and maintaining satisfying and healthy relationships, to positive interactions with others and conflict resolution, to in many cases, making the world a better place, empathy is a defining human characteristic. It’s why we are able to relate to Olivia Rodrigo’s Drivers License, feel joy for our loved ones when they are happy, and give support to those in need.

Thanks for reading!

References

Abramson, L., Uzefovsky, F., Toccaceli, V., & Knafo-Noam, A. (2020). The genetic and environmental origins of emotional and cognitive empathy: Review and meta-analyses of twin studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 114, 113-133. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.03.023

Banissy, M. J., Kanai, R., Walsh, V., & Rees, G. (2012). Inter-individual differences in empathy are reflected in human brain structure. Neuroimage, 62(3), 2034-2039. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.05.081

Beadle, J. N., & de la Vega, C. E. (2019). Impact of Aging on Empathy: Review of Psychological and Neural Mechanisms. Front Psychiatry, 10, 331. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00331

Davis, M. H. (1980). Individual Differences in Empathy: A Multidimensional Approach. University of Texas at Austin

Davis, M. H., Luce, C., & Kraus, S. J. (1994). The heritability of characteristics associated with dispositional empathy. J Pers, 62(3), 369-391. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.1994.tb00302.x

Devlin HC, Zaki J, Ong DC, Gruber J (2014) Not As Good as You Think? Trait Positive Emotion

Is Associated with Increased Self-Reported Empathy but Decreased Empathic Performance. PLOS ONE 9(10): e110470. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0110470

De Waal, F. B. (2008). Putting the altruism back into altruism: The evolution of empathy. Annual Review of Psychology, 59, 279-300.

Fredrickson, Barbara L. (1998). What Good Are Positive Emotions? Rev Gen Psychol. 1998 Sep; 2(3): 300–319.

Han, J. L., & Pappas, T. N. (2018). A Review of Empathy, Its Importance, and Its Teaching in Surgical Training. J Surg Educ, 75(1), 88-94. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2017.06.035

Perry, J. (2021, February 19). Lecturette 5: Empathy. In PSY1535 – Psychology of Social Connection and Belonging: Spring 2021 [Lecture video]. https://canvas.harvard.edu/courses/85306/pages/week-5-module-empathy

Rodrigo, O. (2021). drivers license. On drivers license (single). Geffen Records, Interscope Records.

Schapira, R., Anger Elfenbein, H., Amichay-Setter, M., Zahn-Waxler, C., & Knafo-Noam, A. (2019). Shared Environment Effects on Children’s Emotion Recognition. Front Psychiatry, 10, 215. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00215

Zaki, J. (2014). Empathy: A motivated account. Psychological Bulletin, 140(6), 1608.

Zaki, J., & Cikara, M. (2015). Addressing empathic failures. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 24(6), 471-476.

Tags: Uncategorized

February 13th, 2021 · 7 Comments

[Ari]

The other day, I was walking down the street and I spotted another person walking towards me up ahead. They got closer and closer, seeming to walk in the middle of the sidewalk, unable to pick a side. Finally, the moment of reckoning happens. We both step to the same side. Then immediately to the other side. All accompanied with some awkward laughs and muttered apologies. Hopefully it stops there. BUT it doesn’t always. It just keeps happening, and sometimes I worry I’ll be eternally stuck awkwardly mirroring some random stranger.

Something sort of like this. I can’t imagine anyone really wanting to be caught in this situation, outside of a rom-com. It’s NEVER as cute as they make it look.

This whole situation is incredibly uncomfortable but slightly better when it occurs between someone you know. Even better if it’s a sibling you have a good relationship with. Whenever this happens with my brother and I, we wrestle and pretend like our encounter never happened once the moment passes. Sibling relationships will probably be the longest relationship a person has (in general). So with this extraordinary relationship, does this change mimicry interactions, specifically when compared to strangers?

What I have deemed “the sidewalk shuffle” may be slightly less awkward between friends when compared to strangers. Interactions between strangers are just that. Strange. But imitation and mimicry can actually make some interactions better. Mimicry is much more common than the average person probably thinks and makes these interactions smoother and can lead to increased feelings of affiliation (Leander et al., 2012). Mimicry tends not to happen to the same extent with strangers than with friends or closer acquaintances (Yabar, et al., 2006). People also feel inappropriate levels of mimicry when meeting people for the first time are off-putting, whether it is over-imitating or under-imitating (Lakin & Chartrand, 2003). Imitation and the “correct” amount are very context dependent. For example, being a part of an in-group, like both participants being Christian, can lead to increased mimicry and participants generally reporting a greater liking for the other in lab settings (Yabar, et al., 2006).

On the opposite end of the spectrum, belonging to an outgroup (not quite dislike, just different) has been shown to actually decrease imitation in lab settings and may derive from an attempt to further distance themselves from those in the outgroup (Yabar et al., 2006).

Liking or disliking someone seems to have a very big impact on the amount of mimicry occurring in social interactions. With that in mind, the sometimes-complicated sibling relationships and mimicry are on a very different level.

Siblings [Ellie]

Siblings are weird. There aren’t many people in the world that we can go from loving to hating (while also still loving) and back again in the span of about three seconds. As someone with six siblings, I have plenty of firsthand experience with the treasured and often complicated relationships involved with having brothers and sisters.

The concept of imitation takes on a different role with siblings than it does with others. As previously mentioned, social mimicry can be used as a technique in affiliating with others and determining, or trying to increase one’s own, likability (Lakin & Chartrand, 2003). We know most siblings have the tendency to imitate each other. Seriously, what parent hasn’t witnessed a meltdown or two that starts with “SHE’S COPYING ME!”? With siblings, however, there’s an additional influence that comes into play.

Studies have shown that siblings play a significant role in the social and cognitive development of infants and toddlers (Howe & Recchia, 2014). Importantly, kids learn a lot from their brothers and sisters by watching them and observing how they move about in the world (Barr & Hayne, 2003). I learned a ton from my sister growing up, however it wasn’t necessarily because she was an expert teacher. I watched her dance and learned to love dancing; I saw her helping our parents cook dinner and I wanted to help as well. My older sister had this powerful influence on me by being a relatable person whom I felt comfortable imitating, and consequently learning from.

But how much of an influence can imitating siblings really have on development? It’s actually quite significant. Because infants show the ability to imitate at as early as six months of age (Collie & Hayne, 2003), older siblings are some of the first teachers in infants’ lives. The infants aren’t just learning unrelated skills via mimicry, though; they’re also perfecting the art of imitation itself. One study showed that children with brothers and sisters are better at imitating than those without. In the study, children with siblings had the tendency to observe and copy the behaviors of others without instruction more than only children did (Barr & Hayne, 2003).

So, children with siblings are better imitators, why does this matter? The link between mimicry and affiliation indicates that good imitators would be better at creating connections with others and avoiding the off-putting nature of over and under imitation. In fact, infants who are strong imitators are known to be stronger social communicators, especially in terms of language understanding (Hanika & Boyer, 2019). Having infants develop this skill early on sets them up for success in social situations in the future.

Perfecting the social art that is imitation can have various benefits outside of increasing your winning percentage in Simon Says. Mimicry is vital in many different social interactions, and people have an intuitive sense of how much they like someone which is linked, at least somewhat, to imitation levels (Lakin & Chartrand, 2003). Mimicry with strangers and acquaintances is strongly studied in this affiliative context, but it takes on a strong role in the development of young children with siblings. Imitation for those children is a powerful learning mechanism, that teaches not only new motor skills but also social skills, like mimicry itself. With all of that said, I guess I should probably reach out to my sister and thank her for being there for me to copy all those years….

References

Awkward Encounter | The Amazing World of Gumball | Cartoon Network. (2016). Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dBnFr57KZIY.

Barr, Rachel, & Hayne, Harlene. (2003). It’s Not What You Know, It’s Who You Know: Older siblings facilitate imitation during infancy. International Journal of Early Years Education,11(1), 7-21. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966976032000066055

Collie, Rachael, & Hayne, Harlene. (1999). Deferred imitation by 6‐ and 9‐month‐old Infants: More evidence for declarative memory. Developmental Psychobiology, 35(2), 83-90. https://onlinelibrary-wiley-com.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/doi/pdfdirect/10.1002/(SICI)1098-2302(199909)35%3A2%3C83%3A%3AAID-DEV1%3E3.0.CO%3B2-S

Hanika, Leslie, & Boyer, Wanda. (2019) Imitation and Social Communication in Infants. Early Childhood Education Journal, 47(5), 615–626. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-019-00943-7

Howe, Nina, & Recchia, Holly. (2014). Sibling Relations and Their Impact on Children’s Development. Encyclopedia on Early Childhood Development, 1-8. http://www.child-encyclopedia.com/peer-relations/according-experts/sibling-relations-and-their-impact-childrens-development

Lakin, J. L., & Chartrand, T. L. (2003). Using Nonconscious Behavioral Mimicry to Create Affiliation and Rapport. Psychological Science, 14(4), 334–339. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.14481

Leander, N. P., Chartrand, T. L., & Bargh, J. A. (2012). You Give Me the Chills: Embodied Reactions to Inappropriate Amounts of Behavioral Mimicry. Psychological Science, 23(7), 772–779. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611434535

Yabar, Y., Johnston, L., Miles, L., & Peace, V. (2006). Implicit Behavioral Mimicry: Investigating the Impact of Group Membership. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 30(3), 97–113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10919-006-0010-6

Tags: Uncategorized