[Ellie]

The Beatles, the Boston Red Sox, the Avengers. Everywhere we look people join together with others who share the same goals, passions, or superhero-like abilities which make them part of a distinct group. This semester, we’ve spent each class dissecting our need to belong, and our group associations constitute a huge component of fulfilling that need. Lara, Ari, and I each belong to sports teams here on campus which have provided unique group environments throughout our time here. We are excited to share the experiences we’ve had on the dance, soccer, and rugby teams as we examine some of the benefits and drawbacks of group membership.

Coming to college, I knew very little other than the fact that I was going to be completely out of my element and that I was going to go crazy if I didn’t find a way to continue dancing. As a lifelong ballerina but yearning to try out something new, I adventured to an Expressions hip-hop workshop during opening days (that performance was laughable, a ballerina doing hip-hop?) and was approached by two of my now teammates who encouraged me to come to Crimson Dance Team (CDT!!!) auditions the next day. Apparently, they were impressed by my ability to count to eight and sassy walk with the best of ‘em (or at least that’s what they told me after I made the team).

The first thing that struck me about CDT was how different everyone was, putting aside our identifications as dancers and Harvard students. We come from a variety of dance backgrounds (some competitive, some ballet and jazz, some hip-hop, etc.) and, in my years on the team, we’ve had members from more than ten states and four countries with countless other identities and life experiences. The ability to bring different people together can be very beneficial for groups by increasing the number of perspectives and amount of knowledge contributed to achieving a goal (Cheng, Sanchez-Burks, & Lee, 2008). On CDT, that can mean offering different approaches to cleaning a dance (working on each individual component of a move so everyone is in perfect unison) or suggesting team building strategies; the more people we have making unique contributions, the more competitive we can be as a group. Groups are also just a great way to meet people who come from all walks of life in order to expose yourself to these different perspectives.

Aside from bringing different people together, teams (and other groups) have many other benefits. We know that group membership increases our overall sense of belonging (Baumeister & Leary, 1995), but this is especially salient following rejection in other social environments. When people experience rejection, they gravitate towards and find more meaning in their pre-established groups in order to fix their dampened sense of belonging (Knowles & Gardner, 2008). Being a part of the dance team has definitely benefited me when it comes to finding my place at Harvard and having people to turn to when things are a bit rough. Team membership generally can have many positive attributes when it comes to social connection, however there are also some potential drawbacks which must be examined in order to get a complete picture of what it means to belong to this type of group.

[Lara]

“One last rep, go Gibby!!” In between the beating of my heart in my ears, I hear my teammates yelling my nickname as I turn for the last conditioning sprint of the workout. Fighting through the pain and lactic acid filling my thighs with concrete, it’s their loud encouragement that gets me through that last repetition. My team informs a large part of my identity, at Harvard and beyond; being a student-athlete fills me with pride, responsibility, and an inherent belonging to the entire athletic community. Group membership to the soccer team provides me with the opportunity to grow and meet goals together, creating an interdependency. I enjoy this unique dynamic, as we need and rely on every single player to be on board (not literally!) with the team goals in order to win games, championships, and improve both personally and collectively.

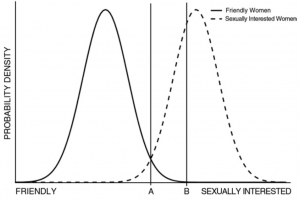

The knowledge that I’m ‘stuck with’ my 20+ teammates for at least four years somewhat forces acceptance and approval of everyone, however, this also spawns an imbalance between assimilating with the team’s dominant identities in contrast to maintaining individuality. The optimal distinctiveness model describes this dichotomy as opposing needs for assimilation and differentiation, in which we define ourselves using distinctive category memberships (Brewer, 1991). Social identities are strongest in those categorizations that are not too inclusive where they become constraining, while also narrow enough to create a sense of belonging. When groups maintain this balance, we are more likely to identify with them and adopt their principles (Brewer, 1991). Personally, I experienced this conflict in assimilating to the heteronormative environment on my team for my first two years and instinctively ignoring my sexual orientation and exploration. Naturally, I assumed that I was straight, both because of existing team norms and conformity out of fear of rejection or ostracism. The thought of coming out to my team became a very anxiety-inducing experience; I played out drastic events of losing my place in this group and having to quit, even though deep down I anticipated that they would accept me regardless.

Coming out, I did not expect positive reactions from my teammates, as I had concealed this stigmatized identity from them for two years of our interactions. Members of the LGBTQ+ community have been shown to be perceived more negatively when they were associated with people’s ingroups (Lupo & Zárate, 2019). Similarly, early disclosure of homosexuality to a heterosexual study partner, versus later coming out, was predictive of increased liking, closeness, and interest ratings in spending one-on-one time in another study (Dane et al., 2015). Contrary to my knowledge of how people can react, and the imminent threat of losing one of my social identities, I stepped out of my comfort zone and overcame my initial flight reaction to leave the closet. To my surprise, the outcome emulated those results showing that participants reacted more positively for established in-group members (Buliga & MacInnis, 2020). In fact, the pre-existing friendships on my team felt like a buffer to the potentially stigmatized perception they may have had of my ‘non-straight-ness’. Learning about an established friend’s membership to an out-group, in this case sexuality, can be overruled by preceding relationship satisfaction and investment into the friendship through long-term commitment (Rusbult et al., 2012).

So maybe my initial fear and stress reaction were part of an innate fear activation reaction involving the HPA axis, amygdala, and sympathetic nervous system? Maybe my stress of rejection was perspective-taking of my team’s perception that turned disadvantageous to my personal well-being? A theme we have found in this course is that the intense physiological aspect of empathy can be counterproductive in that it produced undue stress, anxiety, and fear in me. We may need to self-regulate this vicarious aspect of empathy to maintain our relationships, and our individuality. Tuning into empathy to connect with my teammates is advantageous to create belonging and powerful group identities, however, it can also lead us to hide, or even lose, a part of ourselves.

[Ari]

Moving to a new place gives people the opportunity to curate the different parts of themselves due to decreased interactions with some of the groups they may have previously strongly identified with. As I prepare for graduation and moving to a new place, one of my main concerns is finding a group of friends. Coming into college, I was *briefly* in a similar situation as I knew of one other person who was going to Harvard but Opening Days, roommates, the mere presence of Berg, and joining the rugby team facilitated meeting new people. What I didn’t expect was exactly how close I would get to some of my teammates. As we learned in class, people in our in-groups are more likely to become and stay friends and sports provided me that space.

According to Graupensperger et al. (2020), small groups, like college club sports, lead to increased group identification which in turn, often leads to group members behaving to fit in and greater team cohesion. As Lara described, this can have a wide range of implications, some stressful, some encouraging. In a study investigating group membership and running, a relatively solitary activity, Evans et al. (2019) found women often report a greater running identity compared to men when linked with a running group. The results suggest those who consider running a part of their identity generally run greater distances on average. This supports my own experiences at the collegiate level with one example being conditioning. Conditioning sessions on my own are not as appealing and I will often try to rope people into conditioning with me because it’s an easy reminder of my membership to a team greater than myself.

Group membership is also based on social identity. The connection between group membership and social identity is moderated by the amount of prosocial or antisocial behavior between members during a given day (Bruner & Benson, 2018). In my own personal experience, team vibes are indicative of whether we’ll have a “good” or “bad” practice; for that reason we make a concerted effort to change our behavior when it seems like we are getting down on ourselves or chippy with teammates. Realizing this relies heavily on the experienced players who know the team to steer the rest of the team in a more constructive direction. This is only possible when teammates know the verbal and physical signs of someone being off track. The more time teams spend together, the closer they tend to get and research suggests this increases an individual’s commitment to the team (Graupensperger et al., 2020). The beginning of the season is challenging as everyone adjusts to new roles, new teammates, and figuring out social connections. As a freshman, I was one of eight walk-ons (only two remained by senior year) and it took some time to settle in and figure who was actually going to become a part of the team. And after winning a national championship in the fall of 2019, I’d say we found our groove.

Rugby is and will continue to be a huge part of my life after college, but instead of being an active member of the team, I will be a part of the Harvard-Radcliffe Rugby alumni group. Sports have been a cornerstone of my life and despite leaving behind the organized, rigorous collegiate sports atmosphere, I’m already looking for teams in my soon-to-be home. After all, the common interest sports provide me makes it easier to meet new people while providing an easy conversation starter that could be the start of meaningful new friendships and group connections.

References

Abramson, L., Uzefovsky, F., Toccaceli, V., & Knafo-Noam, A. (2020). The genetic and environmental origins of emotional and cognitive empathy: Review and meta-analyses of twin studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 114, 113-133. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.03.023

Baumeister, Roy F, & Leary, Mark R. (1995). The Need to Belong. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497-529.

Brewer, M. B. (1991). The social self: On being the same and different at the same time. Personality and social psychology bulletin, 17(5), 475-482.

Bruner, Mark W, & Benson, Alex J. (2018). Evaluating the psychometric properties of the Social Identity Questionnaire for Sport (SIQS). Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 35, 181-188.

Buliga, E., & MacInnis, C. (2020). “How do you like them now?” Expected reactions upon discovering that a friend is a political out-group member. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 37(10-11), 2779-2801.

Cheng, Chi-Ying, Sanchez-Burks, Jeffrey, & Lee, Fiona. (2008). Taking advantage of differences: Increasing team innovation through identity integration. In Diversity and Groups (Vol. 11, pp. 55-73). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Dane, S. K., Masser, B. M., MacDonald, G., & Duck, J. M. (2015). When “in your face” is not out of place: The effect of timing of disclosure of a same-sex dating partner under conditions of contact. PLoS ONE, 10(8), e0135023. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0135023.

Evans, M. Blair, McLaren, Colin, Budziszewski, Ross, & Gilchrist, Jenna. (2019). When a sense of “we” shapes the sense of “me”: Exploring how groups impact running identity and behavior. Self and Identity, 18(3), 227-246.

Graupensperger, Scott, Panza, Michael, & Evans, M. Blair. (2020). Network Centrality, Group Density, and Strength of Social Identification in College Club Sport Teams. Group Dynamics, 24(2), 59-73.

Knowles, Megan L, & Gardner, Wendi L. (2008). Benefits of Membership: The Activation and Amplification of Group Identities in Response to Social Rejection. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 34(9), 1200-1213.

Lupo, A. K., & Zárate, M. A. (2019). When “they” become “us”: The effect of time and ingroup identity on perceptions of gay and lesbian group members. Journal of homosexuality, 66(6), 780-796.

Rusbult, C. E., Agnew, C. R., & Arriaga, X. B. (2012). The investment model of commitment processes. In Handbook of theories of social psychology (pp. 218–231). Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446249222.n37.