Portfolio Introduction

ø

Mason Hsieh

5/4/12

Culture & Belief 12

Portfolio Introduction

On the first day of class, Professor Asani explained how the inspiration behind his unconventional grading style was to push his students to think in new ways to acquire knowledge. The goal of the course was to get us to think outside of the box. Thus the class was not only about religion, but about creativity as well. It was this aspect of Professor Asani’s pedagogy that I fell in love in with. I was so intrigued by this unconventional creativity aspect that I really took this to heart and modeled my portfolio after it. While the portfolio is a collection of creative interpretations on traditional religious discourses, I challenged myself to find unconventional ways to conceptualize them, thus inspiring my innovative visions. My goal was to take the least likely path to depicting the major themes in the class. While this goal in and of itself is a major theme that underlies the inspiration of my creative projects, the projects themselves can be categorized under the major themes of religious “light” and visualization.

When I started the class, I was afraid that I would be unable to come up with works of art under such structured time constraints. Six projects in thirteen weeks, I thought to myself, how could creativity be forced into such a short period of time? While I initially grappled with finding inspiration in the selected readings, I ultimately found that the Islamic concept of “ayat” applied to the creative process.

“Ayats” or signs of God, is an Islamic belief that God is everywhere. Allah is in nature and manifested in everything we see. As stated in the Quran, “wheresoever you look is the face of God” (Quran 2:115). Through starting my creative projects, I found that creativity functions as an analogous construct. Once I began actively looking for creativity in the readings, I found that it was in fact everywhere. Inspiration was in lecture, section, the films we watched, and everywhere I looked.

As an artist outside of the classroom, I realized that I did not have to sit and wait for inspiration to hit me to create works of art. Creativity was an ayat. Perhaps creativity is a godly endeavor, or perhaps it is a gift from God himself. Either way, the class has awakened an active creative mind within me, which I plan to continue and cultivate. It is this creative mind that has led me to the fun, unconventional art pieces that make up my portfolio.

The challenge of creating unconventional art pieces can be seen as the most obvious underlying theme of my collection. I really wanted to think outside of the box and create pieces that no one else would think of: pieces that were truly my own. One of the main ways of achieving this was by taking the focus of discussion readings and reinterpreting them in a completely different medium. For example, the aural Quranic recitation became a visual, synesthetic picture. Standard, linear calligraphy became three-dimensional as a tangible sundial. Poems of love and birds became narrative pictures and origami sculptures respectively. By reinterpreting these readings in entirely different fashions, I was able to fully personalize my creative projects. Ultimately, I am very proud of my completed portfolio. I see it as an accurate representation of my creative mind: fun, unconventional, and colorful. All in all, the creative responses are all art pieces that I would be proud to show my judgmental, Asian parents.

The concept of Light is a major motif in the Islamic tradition, and thus, thematically pervades my portfolio. “God is the Light of the heavens and the earth….God guides to His Light whom He wills (Qu’ran 24:35). Similarly, the light of Muhammad and the prophets is particularly noteworthy. All the prophets, especially Muhammad, are said to have a light within them that makes them beacons to guide others to God’s divine message. Because this idea of light is important to the Islamic discourse, I tried to incorporate it into my creative projects.

All of my projects, both literally and figuratively represent at least one aspect of light. The most explicit links can be seen in the calligraphy project and the n’at poem. The two pieces directly relate to God and Muhammad as figures of light. My calligraphy project, a three-dimensional carving of the word “Allah” as the centerpiece of a sundial explicitly highlights Allah’s power over light. While God is light, light controls time. In this piece, “Allah” literally controls light and the lack thereof. The carving determines where the shadow falls and thus, what time it is. In a similar vein, the n’at poem indicates the importance of Muhammad and the guidance that he provides. The poem proclaims the power and warmth of Muhammad’s spiritual light. The narrator professes his love for Muhammad, suggesting that this love in a sense is another guiding light.

The rest of the creative projects are linked to light as well, but represent a less explicit correlation. These projects are primarily visual, and since light is a necessary component for sight, light plays a big role in how these art pieces are perceived. I categorize these creative projects as visual interpretations of the non-visual themes in the discussion readings. These are the projects that I think really highlight my “outside of the box” creativity. For example, my interpretations of the Quranic recitation and ghazal imagery manifested themselves in visual pictures. I took the original audial and poetic prose and gave them physical forms. In a similar vein, the origami bird sculpture makes a theoretical creature into a tangible figure. To see such projects, one needs vision and light. Light also comes into play in the coloring, shading and shadows of these visual pictures and sculptures.

My personal experience with the art has deepened my connection to the class content. By allowing myself to work with the material on more than just an analytic sense, I have engaged with the content on a mental and visceral level. Before I can take any creative liberties on a discussion reading, I must first fully understand the material and what it is saying. I need to truly grasp the essence of the literature before I can reinterpret it. So to create my projects, I must understand and soak of the meanings behind the readings. Then I let this understanding fuel my creative process. I find that I do not bond with other class’s material in much the same.

Many of the art projects also gave me a first-hand view into Islamic culture I would not have gotten through my normal life. For example, when drawing my visual depiction of the Quranic recitations, I had to listen to the audio recordings on a loop. This allowed me to focus in on the individual sounds. I got to luxuriate the articulation, voice quality and flow of the reader. I also listened to six different recitations of the same verse, something I would never have taken the time to do in my daily life. However, by forcing myself to really focus in on the nuances of the six different readings, I got to experience, first hand, how individualized and beautiful the different recitations can be.

Similarly, though I have no personal experience with Sufi ecstasy, the process of folding cranes for my Simurgh sculpture put me in a meditative state of mind which is the closest equivalent that I have experienced. At moments, while repeating the same hand movements to fold 30 cranes, I realized my mind was completely blank. I almost felt as if I was distanced from my body. I am not sure what Sufi ecstasy feels like, but by engaging in this repetitive motion in an attempts to reinterpret a Sufi poem, I may have gotten closer than ever before.

Many of the art pieces mean a lot to me, as the mediums I use are reminiscent of my childhood and family. Two of the pieces are done in crayon, which in an odd sense seems almost sacrilegious to myself. As a child, coloring with crayon was an activity I did exclusively with my mother. I would not color alone. I would only allow myself to use crayons in her presence. The Quranic Interpretation is the first time I have used crayons without my mother around. Metaphorically, this is huge step for me. In a sense, it represents me stepping out of my childhood role and into my own independence.

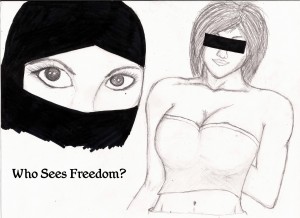

The origami cranes and poster on Western and Islamic dress similarly represent mediums that remind me of my sister and father, respectively. My sister taught me to fold origami, and we would sit in silence and make cranes, penguins, frogs, and every other animal under the sun. The poster, on the other hand, is done primarily in graphite, my father’s preferred medium. He taught me how to shade and contour graphite as well as sharpen and define edges. Thus, I incorporated many of my familial influences into my art projects. They were the ones who taught me how to make art, so it seems only fitting that they are commemorated in my creative pieces.

In conclusion, the creative aspect of this course has helped me learn about religion, creativity and myself. On the most basic of levels, the class is on Islam, a completely foreign tradition and religion to me. By making art to represent Islamic themes, I have bonding with these concepts on a deep level. The ones I have connected with most, and are showcased in this portfolio, are those of “Light” and visualization. As an artist, the creative deadline forced inspiration out of me, and pushed me to grow. It started a creative flame within me that I did not know I had. Finally, by utilizing unconventional mediums, I have made personal connections with and through the art pieces. Ultimately, this portfolio can be seen as a study on the unconventional side of my mind. It represents unconventional, scholarly projects; nontraditional interpretations and mediums; and unusual personal connections. Thus, Professor Asani’s innovative class has truly challenged the way I think about learning.