Muslim Voices in Contemporary World Literatures

ø

Introductory Essay

One of my favorite metaphors in the texts we read this semester for our Freshman Seminar was that of Rumi’s elephant. This elephant, the mystic explained, was standing in the dark, so that each person who touched him described him differently. One man touched the trunk and thought it was a pipe, another touched the tail and compared it to a snake, etc. Yet, none of these men could see the whole animal, and they could only begin to understand the complexity of the elephant itself if they began to speak to one another and describe what they experienced. This class was very much like trying to understand the elephant. We read the perspectives of many authors and then discussed how each new work influenced our vision of Islam. We shared our own stories too, and expanded our worldview through one another’s eyes. Yet, I know I still cannot see the whole elephant of Islam. I cannot know every experience or belief or cultural difference. I cannot know every individual’s story. However, I now know that there is more than just a snake or a fan. I haven’t discovered every part of the elephant, but I have the tools to absorb new stories and continue to expand my view.

Though I never thought of Islamic peoples or countries as all one in the same, the cultural diversity in the tales of our readings was incredible. Moving beyond Sunni/Shi’a and governmental differences, this class captured how local traditions influence religious practice and belief. In The Suns of Independence, we read of Salimata’s near-death experience with FGC (female genital cutting), which shed light on how important cultural factors are in examining someone’s life story. If, for example, we only tried to understand Salimata’s relationship with her husband and desire for pregnancy by relating it to her religion, Islam, we would miss seeing her whole person. Instead, we must see how her botched traditional initiation ritual and subsequent rape, as well as her beliefs as a Muslim, have made her who she is. In the same way that we need to view Salimata as much more complex than her religion, we must also understand the cultural contexts of our other characters.

One of the stories in which this moves beyond the character and into current events is In the Name of God. Ultimately, by reading this story and understanding the motivations of Kada, from poverty and limited options to wanting to stand out, we can see how someone might potentially, even today, be successfully recruited for an extremist religious group. In the Name of God showed us how appealing it would have been for the characters, as the group promises a good salary, true faith, and strong leadership, three things the rest of the society lacks. We can apply what we learned from this story to our evaluation of the current situation. Clearly, poverty and corruption are two important factors in determining whether someone will seek out a new lifestyle; thus, we must address these two issues to ultimately fight unrest.

We read stories from all over the world, including Egypt, Iran, Afghanistan, West Africa, India, and the West. We were able to identify cultural variations and use them to understand the different interpretations of Islam. Governmental control was one such variation that changed the way of life and interpretation of religion. Swallows of Kabul, for example, showed the harshness of living under the Taliban and how religion was used as a way to control the people. Persepolis showed another extreme example of how the state could become obsessed with a certain interpretation of religion and use it to its own advantage. Persepolis also showed how the citizens simply get swept along in the mess of politics. Both of these books filled in some of the gaps in my understanding of Afghanistan and Iran respectively. And, in conjunction with the political commentary in The Beggars’ Strike, I now have a better understanding of how religion can be misused for political gain. Not only does this shed light on the nature of politics and religion, but it also serves as a reminder to not judge countries with national religions (Iran, Saudi Arabia, etc.) as being truly representative of that strain of religion, as the beliefs are often being distorted for political purposes.

However, that also does not mean that the average citizen would be a better representative of each sect or regional variance of religion (in this case, Islam). Instead, we have learned there is no representative, rather a collection of extremely diverse individual stories that we must work to collect and understand, while also keeping in mind that there will always be gaps in our knowledge. As long as we allow literature to fill in our picture of the world but acknowledge we will never be able to know everything, we can be good scholars. This is a fundamental idea behind the cultural studies approach, which we learned about on our first day of class. This approach to the study of religion takes historical, political, economic, social, literary, and artistic factors into consideration when learning about the context of other people, and recognizes each of these factors, as well as religion itself as dynamic elements. This concept, of an ever-changing world, allows us to have a fluid, rather than stagnant, definition of other people and cultures. This approach to the study of religion is the most important concept that I learned in this course.

Beyond general approach, Muslim Voices in Contemporary World Literatures taught me so much about specific ideas in the study of religion. One of the most interesting ideas that we talked about was nationalism. In the history of colonialism, nationalism has come to mean many things, from the liberation of a people to the inconsiderate re-drawing of boundaries by a conquering European nation. Even today, as we learned in class, nationalism is a double-edged sword. Personally, I sway between being a proud American, holding true the values of freedom, equality, and diversity, and wishing I could be from a place that hasn’t caused so many ruinous wars and invaded other parts of the world. Nationalism, like religion, can spur violent fervor and make people think they are better than others. But nationalism, like religion, can also bring people together into strong, supportive communities. What becomes extremely important is that we take responsibility for our actions as people and don’t use religion or nationalism as an excuse for our actions.

This leads us to the idea that religion is constructed, and is not an active player. People can, as we saw in several of our readings, do things in the name of religion. However, religions do not do anything themselves. So, when people blame Islam for being violent or Christianity for being proselytizing, they are mistaken. People are behind the actions, and people choose to interpret the world and their beliefs in their own individual way. Keeping this in mind, we must realize everyone is an individual and avoid categorizing everyone of one group as the same. It was sad to see everyone react to the Paris terrorist attacks by clamoring to raise hurdles for immigrating Muslims. Not all Muslims committed this act of violence and not all Muslims are the same. My classmates and I understand this, but so many people do not. Indeed, it is not a clash of ideologies, but rather, as we talked about in class, a clash of ignorances, as people misunderstand one another and aren’t tolerant.

The way we perceive the world will ultimately affect the type of world we live in. We can choose to take the approach of understanding, education, and tolerance, or we can choose to ignore the differences around us and stand in opposition to all we see as “other”. Every day, I am disheartened by the words of hate I hear and see around me. I cringe at the calls for oppression. Yet, I do understand. It is terrifying to see what people are capable of, and yes, religious extremist groups have done terrible things. But, we should not be led astray by our fear. Instead, we must embrace and learn. That is what I loved so much about this semester of Muslim Voices in Contemporary World Literatures. I loved that I was being fed material to open my eyes and expand my worldview. No one was telling me to hate, and everyone was telling me stories. I loved the tales of our texts, the wisdom of our professor, and the musings of my classmates. I loved that every Tuesday evening I entered a space of curiosity.

Beginning with story time allowed me to learn about the experiences and perspectives of my peers. I was able to learn about more than just the texts by hearing their stories of the week, and I also understood where they were coming from when they made a contribution to a discussion in class. No one was simply stating fact, but rather their opinion as formulated by their life experiences. I really enjoyed our class because everyone was so interesting, and because everyone was so interested in the subject matter. Our conversation never ran dry, and we would always walk back to the yard each night still discussing ideas from class. We also met outside of class, simply to learn more about one another. I also enjoyed that my classmates asked really good questions, as it made class far more interesting. Questions tying our readings to current events were some of my favorite, as the stories provided similar situations or at least cultural context for contemporary debates.

Every individual is made up of many parts. Every community is made up of many individuals. Every society is made up of many communities. This world is made up of many societies. Thus, if our ultimate goal is to understand the world, we must break it into pieces. And, just like the men examined the Rumi’s elephant in the dark room, we must examine whatever is nearest to us to understand that piece of the world. But then, instead of stopping with the idea that we are touching a snake or a fan or a pillar, we must move on to other domains and find more of the elephant. And, for those areas that are too far out of reach, we must listen to the stories of the people on that side of the elephant to discover what they have found. We cannot be every person, so we must share through stories. Muslim Voices in Contemporary World Literatures taught me a lot about the study of religion, the diversity within Islam, and a variety of cultures around the world. I learned from my incredibly interesting and intelligent classmates and a fabulous professor who taught us important background information, gave us a framework for analysis, and allowed our discussions to follow tangents. I looked forward to class every week, and I am sad that the semester is over, though I know I will continue to approach my understanding of the world in the ways I have learned in this class.

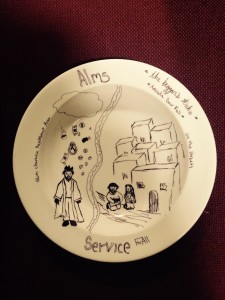

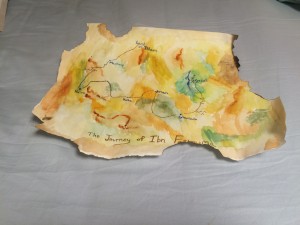

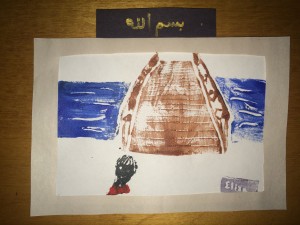

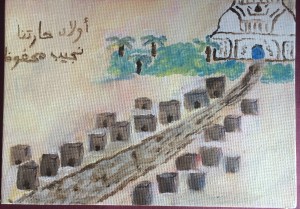

This portfolio of creative works is a collection of my artistic responses to the majority of the readings of this semester’s class. Each week we wrote longer (~700 words) written responses to each of the readings for the week, and these were collected in a discussion format on the class website. Then, with the ideas we voiced in these responses in mind, we had class discussions. From these discussions, we drew the larger themes and ideas of the week, and from there we made creative responses to 10 of the texts. My artistic collection includes paintings, drawings, a poem, a collage, mehndi designs, a print, charcoal, and a sculpture. The 10 texts I responded to are: The Beggars’ Strike, Madras on Rainy Days, The Journey of Ibn Fattouma, In the Name of God, The Children of the Alley, Jasmine and Stars, An Egyptian Childhood, The Complaint and the Answer, The Saint’s Lamp, and We Sinful Women.