Prologue

All the innumerable forms of human spirituality center on the most magnificent of human capacities: the power to commune. The manifestations of this power are myriad and diverse. Congregations hear sermons, we hear moving music, we read and recite the weighty words of prophets and sages, Heaven hears our prayers, and in Islam God speaks back to us through the mouth of the Prophet Muhammad and the text of the Qur’an. I am captivated by every one of these voices, all of them rolling together into one chorus; the Voice of God and the voices of believers seem to resonate with imbued energy, as though they could move mountains with a whisper. Over the course of this class we have experienced this Voice in a variety of beautiful ways through several media, and this principle is what I have attempted to embody in the artistic works you will find here. Thus, Ubiquitous Voice strives to encapsulate the voices of Islam as a religion and as a collective of many peoples.

In AI54, we as a class began by learning away the notion of a “true Islam,” while at once gaining a better understanding of “real Islam.” To achieve this, we took our focus away from some traditional methods of studying religion. For example, Prof. Asani writes in the introduction of Infidel of Love that the “devotional approach… understands a religious tradition primarily in terms of its doctrines, rituals, and practices… It conceives of religious doctrines and practices in monolithic terms…” (Asani 7). On the other hand, the textual approach “regards sacred writings and texts as the authoritative embodiment of a religious tradition. According to this approach, a religion is best understood by reading its scriptures which are perceived as containing its ‘true’ ethos or essence,” (Asani 7).

Instead, we employ a “cultural studies approach,” which analyzes religion by concentrating on “the people who actually practice and interpret it,” and which recognizes religious traditions as “internally diverse and constantly in flux,” (Asani 10). The key notion herein, that of multiplicity within the overarching unity of Islam, is a theme which weaves into every piece of art in Ubiquitous Voice. The first piece, entitled “The Word, the World,” made with brush on canvas, serves a dual purpose: both to symbolize diversity of expression within Islam, and to draw upon its unifying veneration of the Voice of God. As a calligraphy piece, it ties to the huge diversity in the art and customs of the art of Islamic calligraphy; the wealth of methods and styles reflect the pluralistic nature of the religion, as does the range of traditions revolving around calligraphy, such as the Berti practice of “drinking the Koran,” described by A. O. El-Tom. Yet this multiplicity is bound together by God, and “The Word, the World” aims to capture this by symbolizing the Voice of God creating the world. In so doing, the piece also nods to the deep reverence for the spoken word of God in Islamic traditions, as expressed through recitation of the Qur’an, which is believed to be the actual word of God given to Muhammad.

Importantly, “The Word, the World” also draws on the notion of ahl al-Kitab, “people of the book,” an inclusive concept in Islam that means “people of the book.” This refers to peoples who adhere to sacred revelations in the form of scripture, in particular Jews, Christians, and Muslims. “The pluralistic intent of this term is evident in the use of the noun Book in

the singular rather than in plural, as a way of emphasizing that the Jews, Christians, and

Muslims follow one and the same Book, not various conflicting scriptures,” (Asani 114). Indeed, the original meaning of “muslim” encompassed all those who submitted to the One God (Asani 112). As such, I chose to depict a scene that is held in common across Abrahamic traditions, the Taurat/Old Testament story of the Creation. As a testament to the power of Voice, the various aspects of the world all come into being in response to God’s declarations; the story is punctuated by the phrase, “And God said….” Thus, I painted features of nature formed around their respective Arabic words to symbolize nature’s connection to the powerful Word, and the transformative power of the Voice.

Moving on in the course, we delved more into the contextual diversity of Islam, discovering traditions of Shi’i piety such as the Ta’ziyeh, a theatrical tradition relating the martyrdom of Hussayn that has its roots in Persian theater art that predates Islam. We also sampled the vast and colorful tapestry of mosque architecture and design throughout the world. Through readings and film, we explored key elements of mosque design such as the qiblah wall, mihrab, minaret, dome, arches, and a collection of common interior design features known as arabesque.

In response to anti-Islamic sentiments in the United States that often manifest in the protestation of mosques, and in response to competing definitions of what is or is not Islamic, I chose to create a piece that highlights the true haziness of the lines that define Islamic culture. In “Mutual Magnification,” I created a photography album of my personal favorite offspring of cultural fusion: the Connecticut State Capitol in Hartford. The building’s exterior features a mix of French and Victorian architectural influences, allowing it to fit harmoniously in a New England city. However, the interior design is directly inspired by Arabic regional design and, in particular, mosque design. To me, this utilization of design traditions from different cultures causes us to lose confidence in what might have been confident assumptions about what is or is not Islamic, a key theme in this course. I’ve used camera angle and lighting to emphasize similarities to mosque design, showing light streaming through pointed arches, the sense of space offered by rows of spaced columns, et cetera.

The Capitol uses these design features for many of the same reasons they are included in mosques. It was built in the 19th century, a time of unprecedented secularism and a sharp decline in the role of religious observance in public life. In my own theory, the utilization of traditionally religious designs in secular settings both “robs from” and, in a way, perpetuates, their religious significance. Domes and arches still represent the heavens and guide the eyes skyward; pillars create a sense of infinity; vegetative designs connect architecture with nature; and geometric patterns draw upon the authority of simple but beautiful mathematical principles. Thereby, the architect of the Capitol lends authority to the state and splendor to the population by employing the same tools that mosque architects use to embody the authority of God and the splendor of Heaven.

We closed the first half of the course by exploring local traditions of Islam, colored by the culture and history of their contexts. In so doing, we became more aware of the fallacy of the monolithic image of Islam which is so familiar in mass media. We broadened our understanding of Muslim traditions by studying such traditions as bridal symbolism found in the Shi’i Ginans and the moral qasidah songs from Indonesia. We learned the importance of not equating “Muslim” with “Arab” or with a certain single culture or set of universal practices, instead seeing Islam as taking many forms through many people in diverse cultural contexts around the globe. Thus, Islam is a chorus, with over a billion Voices rolling together into one.

Yet we also learned about pressures from within and without to stifle the rich complexity of Islamic culture and to achieve uniformity. Through lecture and readings we learned about conflicts between Sunni and Shi’i Muslims over the rightful lineage of authority following the death of Muhammad, the tendency of Western scholars to define religion by doctrine and categorize “orthodoxy” versus “unorthodoxy,” and the contempt of some authorities such as the Saudi government towards practices like Sufism and the construction of gravestones. The third work, “Silenced on All Sides,” made with oil pastel on paper, seeks to create sympathy for diversity of customs in Islam. The colorful mosque in the center, which I will call “Pluralism,” represents the many unique traditions of Muslim people that might not be considered “orthodox” or even “Islamic” by many authorities, but which are a part of Muslim culture nevertheless, and add to the wealth and beauty of that culture with their variety. Pluralism is pressured on the right by the Faisal Mosque on a background of green to represent the Saudi flag. I chose this Mosque, built in Pakistan but with Saudi supervision and design, as a symbol of cultural imposition and a push for Islamic uniformity by some authorities of Saudi Arabia, and in general as a symbol for all those Muslims who aim to expunge diversity within the religion. From the left, Pluralism is pressured by an archetypal mainline Protestant church on a background of the American flag. This represents pressures from Western scholars to categorize and define Islam by rigid standards and strip away the complexity of its identity, and also makes note of the identification of the West, and particularly the United States, as essentially Christian. This latter notion is a core philosophy that drives Islamophobia and intolerance in many circles, and an altogether rejection of Islam combined with a belief in the superiority of Christianity. Below Pluralism is a field of fuliginous black, a symbol of the radicalism and violence that exist today and tries to align itself with Islam for legitimacy, leading only to hate, destruction, and confusion over what it means to be a Muslim. With this piece, my hope was to instill thoughtfulness in the viewer towards the many Voices of Islamic culture that are chronically unheard by most ears.

In the second have the course, we progressed by looking into the Muslim spiritual practices characterized as “Sufism.” We discussed the respect for sagacious shaikhs, the enthralling qualities of Sufi music and dance, and the Persian-influenced poetic traditions of the ghazal love-lyric and mathnawi narrative epic. We encountered a gorgeous example of the mathnawi: Attar’s Conference of the Birds. In homage to this work, I wrote a counterpart in the form of a ghazal, “Ascent to Salat.” In it I include much of the symbolic themes of Conference, such as the notion of a transformative and painful spiritual journey. I also employ imagery used specifically in Conference, including a repeated use of flame imagery, the Self as heavy mail, the searing and transforming gaze of a pious person, and the goldfinch. Thus the poem has the narrative elements of a mathnawi with the structure of a ghazal, insofar it is arranged in couplets which all have their final word in common (“burned”). The emphasis is on a theme which permeates the breadth and depth of Sufi philosophy, the theme that the Self is a barrier to God that is overcome through painful, metamorphic acts of active piety and ecstasy.

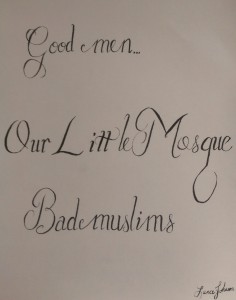

In the final weeks of the course, we discussed the role of women within Islam. In an especially powerful set of readings, we listened to the Voices of accomplished female Muslim writers who speak out in the form of literature against women’s crisis of identity and submission in various contexts of the Islamic world. Through such works as Persepolis, Sultana’s Dream, “We Sinful Women” and “Little Mosque Poems,” we connected with women who grew up in the midst of war, who dream of a perfect world for women, and who satirize the submissive role of women found in many Islamic cultural contexts. I focused on Mohja Kahf’s “Little Mosque Poems” as the inspiration for my next piece in Ubiquitous Voice, which entitled “Our Little Mosque” and was made using line-varying fountain pen. I use this piece to point to the divisions often placed between Muslim men and women, divisions that are often reinforced by the religious institution. Mohja Kahf describes her “mosque,” symbolizing her local religious setting, as highly judgmental, exclusive, and overly paranoid with ritual while failing to demonstrate human decency and understanding. I symbolize the divide between male and female Muslims by using the phrase “Our Little Mosque” to bisect the page, just as religious institutions will often physically and socially divide men and women. Women often must use separate prayer spaces and entrances, and are subject to specific forms of moralizing scrutiny, and the standards of piety and morality for men and women are often hugely different. Therefore, in the half of the page representing the “male” side, I’ve written “Good Men”, referring to those who are admitted to the beautiful part of the mosque in Kahf’s poem, who are all male.

My little mosque has a Persian carpet

depicting trees of paradise

in the men’s section, which you enter

through a lovely classical arch

The women’s section features

well, nothing

The other half of the page, representing “women,” bears the phrase, “Bad muslims.” This emphasizes that women are Muslims, no differently than men, but that their femaleness is perceived as working against them in achieving the status of a good, worthy Muslim.

We finally tied up the course by experiencing the contemporary Voice of Islam. This involved a return to music and mosque architecture, but in varieties that serve the Muslim communities of the modern world. We also read and discussed Mohsin Hamid’s The Reluctant Fundamentalist, a novel that lends a voice to Muslim identity before and after the events of 9/11. My poem, the last installment of Ubiquitous Voice which is called “Easy There Tiger,” seeks to emulate the sharp turn in mood that occurs in the book with the arrival of the attacks. The poem begins with optimism, with imagery of a commencing hunt. This aligns with the start of Changez’s story in The Reluctant Fundamentalist, where he is a vibrant young man fresh from college and brimming with ambition. Then the hunt is reversed, and the “tiger” character is himself caught, and a female presence is introduced. This parallel’s Changez’s love interest Erica, a symbol of perfection in class, talent, personality, and physique. I represent her as a lioness, and as a pearl in the oyster of the world, an absolute pinnacle goal for Changez to reach. The tone remains upbeat, newsy, and congratulatory, mirroring Changez’s sleek and shiny Wall Street world and imitating the voice and attitude of his paternal mentor, Jim. But a break in the poem, coupled with the harsh sound of a crack, symbolizes the sudden and dramatic 9/11 attacks which turn the novel, and the poem, to a grave and ominous tone. Likewise Erica and the poem’s female figure are revealed as flawed, not as shiny and perfect as once thought, so much so that she must “leave” by dying. Changez, too must leave, and I close the poem by comparing this to the suicide of Erica; his departure from America is the symbolic death of his earlier persona which is replaced by a wiser but more cynical man. Overall, the poem seeks to embody the modernity and speed that are so eloquently conveyed by Hamid.

Ubiquitous Voice traces the narrative of our course on art, culture, and religion by focusing on the voice, the expression that art offers. It begins by focusing on the all-powerful voice of God then moves on to the often unheard voices of many minorities and lesser-known customs which make up Islam and broaden our definition of what is Islamic. It then explores the older, classical, sage voice of the Sufi poet, and then the modern, less traditional, and more political voices of Muslim female poets. Finally, it touches upon what it means to be a Muslim in the modern world, given many events that have radically altered the world’s view of Islam; and, in observing the modern state of Islam, it touches upon the future, questioning the fate of Muslim identity in the years to come. For me, this collection of works is a journey in discovering more about the world and subsequently more about myself. It is a task of understanding how my own voice fits within the soundscape of a world-spanning culture.