In the beginning was the browser, and the browser was yours. You drove it on the Information Superhighway of the World Wide Web:

As a driver, you experienced the same kind of independence that you did with a car. You had a private space inside a private vehicle that you alone operated. You thought and spoke about it with first person possessive pronouns. So, just as you still think and speak of my car, with my engine and my tires, you also thought and spoke of my browser with my bookmarks and my history.

But, because the Web was designed on the client-server model (aka calf-cow), sites could do what t hey wanted with your vehicle. So, while each site gave you both what you came for (pages, usually), it also gave you cookies to help you both remember where you were the last time you visited. And, for the convenience of you both, it also gave you a shopping cart. Thus, to them, and to you, this is what your browser became:

But there was a cost to this: you were no longer an independent human being with your own private space, but a shopper in the site’s private space. This asymmetry of power and dependence was — and remains — so absolute that it became pro forma for sites and services to use the first person possessive pronoun for you: myspace, myfitnesspal, myverizon. This only made sense in the context of not being able to say it for ourselves.

As a result, our browsers on the commercial Web are not really our own. They are re-skinned at each site with whatever the site wants to make of them:

On the commercial Web, we may still think we’re drivers, but inside each site we are passengers — or, in the now-favored lingo of retailing, “guests.”

Being guests rather than drivers has put us each in a slow-cook hell with these features/bugs:

- Accumulating up to hundreds of different password-login combinations

- Needing to fill and re-fill hundreds of mostly-redundant forms, over and over again

- Submiting just as often to one-sided terms of service that we never read because there’s no point to it

This absolute submissiveness, this complete yielding of personal power to “providers” of all kinds, has boundless upsides. But it has been a Faustian bargain from the start. What we deal away is our time and our agency, both of which matter to our souls.

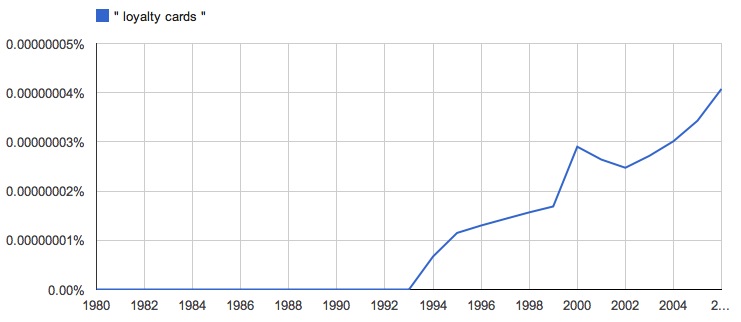

Seeing the success to be found in dominating customers online, brick-and-mortar retailers have replicated some of the same systems, requiring that regular customers carry around loyalty cards, one for each store. Here’s how “loyalty cards” shows up in Google’s Ngram Viewer:

The timing is no coincidence. Nor are the inconveniences these cards impose on customers and stores alike. But, so long as “free” means “your choice of captor,” the captive-captor system prevails.

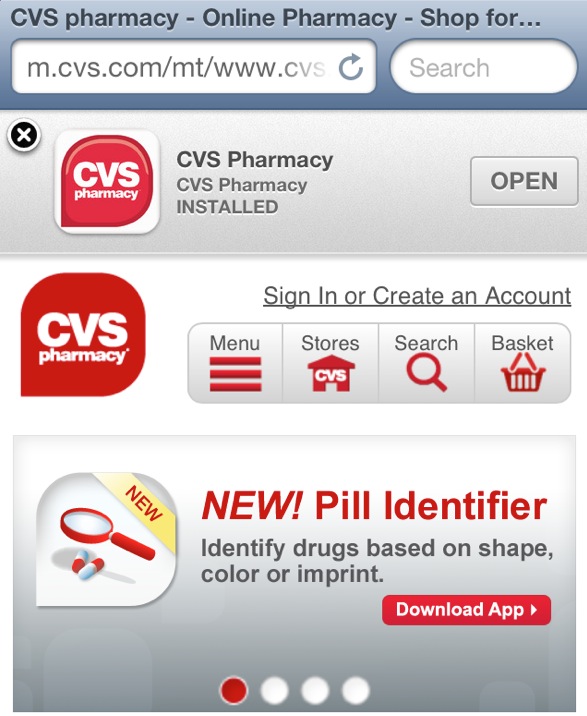

That’s what’s happening in the mobile space as well.Shopping carts on websites have become the shopping apps on smartphones. The result is an all-proprietary subset of the World Wide Web:

And they proliferate. If you go to CVS, you get told to download an app. If you’ve already done that, you get told to download another one:

Or so it appears. I just spent 20 minutes trying to figure out if the Pill Identifier is a feature of the CVS pharmacy app, or an app of its own. Hard to tell when you look up “cvs” on Apple’s App Store app:

To CVS, these are all conveniences for both of you. Never mind that these end up cluttering your phones. Nor that you can only get these (at least on the iPhone) at just Apple’s store, and that your phone company also controls what you can do with it (far more than any car company controls what you can do with the car you buy, lease or rent from them). The inconvenience is yours, not theirs.

The benefits, again, are enormous. For example, it is surely a good thing, for some people, to know what kinds of pills they have. And it’s a good thing that CVS provides a way to do that. But it’s CVS’s app, not yours.

To get the difference, consider an ordinary thermometer. When you buy one from CVS, it’s yours when you walk out of the store. It isn’t CVS’s any more. Maybe it would be good if the thermometer were smart enough to communicate your temperature to your doctor or to CVS. But that option should be yours, not CVS’s. Yet there are many who would urge CVS to get your temperature, if it can. And these are the people who are running the “big data” conversation today, at least around marketing.

We are already down a steep and slippery slope here.

See, once you have an app, it’s hard to know for sure what information about you and your life the app is sending back to the company, or to its third parties. According to the Wall Street Journal, countless apps are reporting on you and your activities to marketers, without telling you that’s what they’re doing. Or at least not in an obvious way. Yes, they have privacy policies, but nearly all of them reserve the right to change those. And yes, you do have the choice to not participate in the app marketplace. But as the world becomes more and more networked, that becomes less and less of a practical option.

In respect to the Faustian bargain with the all-silo marketplace, it doesn’t matter how good the silos get. They are still silos. Making better silos doesn’t solve the problem.

After awhile all this power asymmetry adds up, and at some point it breaks. Our job with VRM is to make that break happen — by showing customers and providers alike that there are better ways to operate a free marketplace, starting with free customers. We do that through tools and services that are more like cars than like shopping carts: that make us both independent and equipped to engage.

A list of VRM developers is here.

Bonus links:

- The Mind of a Customer, by JP Rangaswami

- The Intention Economy: When Customers Take Charge

- Mozilla Persona

- Ting Implements Mozilla Persona