@United just left my iPad at Seat 31k of UA 934 at Heathrow. Can you have somebody check on it before the plane turns around? Thanks! #vrm

Month: January 2015

My last post asked, How do you maximize the help that companies and customers give each other? My short answer is in the headline above. Let me explain.

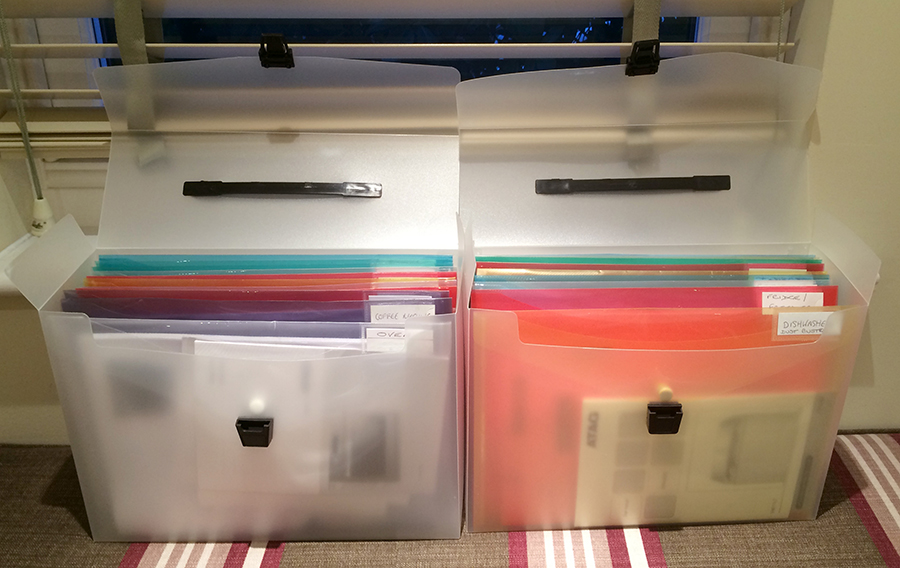

The house where I’m a guest in London has clouds for all its appliances. All the clouds are physical. Here they are:

Here is a closer look at some of them:

Each envelope contains installation and instruction manuals, warranty information and other useful stuff. For example, today I used an instruction manual to puzzle out what these symbols on the kitchen’s built-in microwave oven mean:

Now let’s say I didn’t have the directions handy. How would I find them? Obviously, on the Web, right? I mean, you’d think.

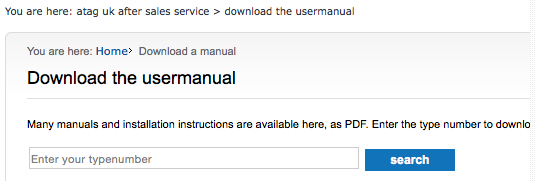

So I went to the site of Atag, the oven’s maker. From eyeballing the microwave, I gathered that the one in the kitchen is this one: the Combi-Microwave MA4211B. On the Atag website I found it buried in Kitchen Appliances —> Collection —> Microwaves, where it might also be the MA4211A or MA4211T. Hard to tell. Directions for its use appeared to be under Quality and Service —> Visit ATAG Service Support. There I found this:

When I clicked on “Download the User Manual,” I got this:

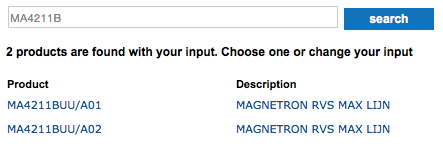

For “type number” I guessed MA4211B, entered it in the search field and got this:

I got the same results clicking on both:

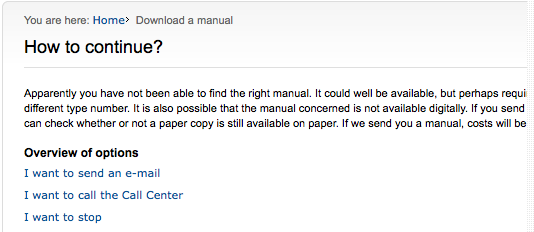

Nothing actually downloaded, and the Acrobat Reader information was useless to me. So I clicked on “No.” That got me this:

I then hit “I want to stop.” That looped me back to the search panel, three screenshots up from here.

In other words, a complete fail. Since the copyright notice is dated 2007 — eight years ago — I assume this fail is a fossil.

There are three reasons for this fail, and why its endemic to the entire service industry:

- The company bears the full burden of customer service.

- Every company serves customers differently.

- There is no single standard or normalized way for companies and customers to inform each other online.

What’s missing is a way to give customers scale — for the good of both themselves and the companies they deal with. Customers have scale with cash, credit cards, telephony, email and many other tools and systems. But not yet with a mechanism for connecting to any company and exchanging useful information in a standard way.

We’ve been moving in that direction in the VRM development community, by working on personal data services, stores, lockers, vaults and clouds. Those are all important and essential efforts, but they have not yet converged around common standards, protocols and customer experiences. Hence, scale awaits. What this house models, with its easily-accessed envelopes for every appliance, is a kind of scale: a simple and standardized way of dealing with many different suppliers — a way that is the customer’s own.

Now let’s imagine a simple digital container for each appliance’s information: its own cloud. In form and use, it would be as simple and standard as a file folder. It would arrive along with the product, belong to the customer*, and live in the customer’s own personal data service, store, locker, vault, cloud or old-fashioned hard drive. Or, customers could create them for themselves, just like the owner of the house created those file folders for every appliance. Put on the Net, each appliance would join the Internet of Things, without requiring any native intelligence on the things themselves.

There, on the Net, companies could send product updates and notifications directly into the clouds of each customer’s things. And customers could file suggestions for product improvements, along with occasional service requests.

This would make every product’s cloud a relationship platform: a conduit though which the long-held dreams of constant product improvement and maximized customer service can come true.

Neither of those dreams can come true as long as every product maker bears the full responsibility for intelligence gathering and customer support — and does those differently than every other company. The only way they can come true is if the customers and their things have one set of standard ways to stay in touch and help each other. That’s what clouds for things will do. I see no other way.

So let’s get down to it, starting with a meme/hashtag representing Clouds For Things : #CFT.

Next, #VRM developers old and new need to gather around standard code, practices and protocols that can make #CFT take off. Right now the big boys are sucking at that, building feudal fiefdoms that give us the AOL/Compuserve/Prodigy of things, rather than the Internet of Things. For the whole story on this mess, read Bruce Sterling‘s e-book/essay The Epic Struggle for the Internet of Things, or the chunks of it at BoingBoing and in this piece I wrote here for Linux Journal.

We have a perfect venue for doing the Good Work required for both IoT and CFT — with IIW, which is coming up early this spring: 7-9 April. It’s an inexpensive unconference in the heart of Silicon Valley, with no speakers or panels. It’s all breakouts, where participants choose the topics and work gets done. Register here.

We also have a lot of thinking and working already underway. The best documented work, I believe, is by Phil Windley (who calls CFTs picos, for persistent compute objects). His operating system for picos is CloudOS. His holdings-forth on personal clouds are here. It’s all a good basis, but it doesn’t need to be the only one.

What matters is that #CFT is a $trillion market opportunity. Let’s grab it.

* I just added this, because I can see from Johannes Ernst’s post here that I didn’t make it clear enough.

I’m not talking just about what companies and customers learn from each other through the sales, service and surveys — the Three S’s. Nor am I talking only about improving the “customer experience,” (a topic that has been buzzing upward over the last few years). I’m talking about how companies and customers help each other out. I mean really help. Constantly.

One way, of course, is by talking to each other. There are exemplars of this. Among big companies, Apple leads the way, gathering intelligence though its responsive call center and the Genius bars at its retail stores. Among small companies, my favorite example is Ting, a U.S. mobile phone carrier. According to Consumer Reports, Ting is tops in customer satisfaction, while Sprint is dead last. Here’s what’s interesting about that: Ting runs on the Sprint network. Meaning the actual performance of the network is the same for both. This gives us a kind of a controlled study: one network, two vastly different levels of customer satisfaction. Here are two reasons for that difference:

- Ting’s offerings are simple. They have rates, not plans. You only pay for what you use. That’s it. And usage is low in cost. Sprint, Verizon and AT&T, on the other hand, all comprise a confusopoly. They offer complex, confusing and changing plans, on purpose. In confusopolies, the cognitive overhead for both companies and customers is high. So are marketing, operational and administrative overheads. That’s why they are all more expensive than Ting, and unloved as well — even as, no doubt, they have CRM systems that pay close attention to the customer service performance of their website and call center.

- Ting actually talks to customers. They are fanatical about person-to-person service, which means both sides learn from each other. Directly. Ting’s products and services are constantly improved by intelligence coming directly from customers. And customers can sense it. Directly.

Now, what about the times when you and the company are not talking to each other? For example, when you just want something to work, or to work better?. Or when you think of a way a product or a service can be improved somehow, but don’t want to go through the hassle of trying to get in touch with the company?

I answer that in the next post.

Yesterday I left my iPad on a United airplane and got it back. How it happened is a story of sCRM (social Customer Relationship Management) and VRM (Vendor Relationship Management) at work.

The flight was United 934 from Los Angeles to London. When I arrived at around 11am, I did my usual checking around my seat for things easily lost and forgotten: my wallet, passport, earphones, camera, lens cap, phone, iPad, USB and AC power cables and so on. And, as always, I looked under and around the seat and in the seat pocket in front of me.

Where I failed was with the seat pocket. The iPad is a new-ish one (an Air), which is much thinner and lighter than my old one (the original model). It was stuffed with thicker magazines, barf bag, Sky Mall and so on, in the pocket-within-the pocket. I didn’t see or feel it when I looked in there. It wasn’t until I got to London and set up my laptop and other gear that I realized I had forgotten it.

After going through about ten minutes of self-recrimination for my stupidity, I called United and got walked through the process of filing a lost item report, deep inside the company website. Then I called Heathrow’s lost & found number, which (it turns out) is an independent contractor that works only with certain airlines and terminals. United and Terminal 2 are not among them. Then I fired up my FindMyiPhone app, but alas the iPad was offline. (It’s a Verizon/CDMA model, while all my other cellular devices are T-Mobile/GSM, so it won’t work outside North Amercia; so it’s Wi-Fi only.)

Then I went on Twitter and started this exchange:

Between #2 and #3, my wife said “Go out there.” This had worked for her a few years back when she forgot her carry-on bag in a shuttle van from Logan Airport in Boston. Se went out there and got help from lots of friendly human beings — especially the police, with whom she sat watching video cameras, live, to spot the van in which she left the bag.

I had the same good luck at Heathrow.

When I got there I went to the check-in kiosk in front of the United counter at Terminal 2, where a pair of kind young professionals immediately went to work helping me after I told them my flight and seat numbers. The woman looked up the flight and the gate, got on her phone and called somebody she knew who was in a position to locate the iPad. (I’m assuming this person was at the gate, but I don’t know for sure.) After a few minutes of conversation, she said, “We’ve got it,” and told me it would take about 45 minutes to ferry it in from the gate. After about that much time, her male co-worker brought over the iPad, had me punch in the code on the front (to make sure it was mine), and I was on my way.

The VRM part of this was all human, and depended on the good will (and available time) of the people involved. The only facilitating system in place was cellular telephony. @United’s lost & found, and sCRM system might have brought back the iPad in the long run, what worked was face-to-face interaction.

Is it possible to scale that? I think so, but we can’t depend on vendors alone to do the scaling. In fact, I think they’ve gone as far as they can. (In @United’s case by monitoring social media closely, with human beings.)

We need standardized tools on the individual’s side — first person technologies — that scale across multiple vendors. (In this case, for example, across United, Heathrow and public safety systems.)

I have thoughts on specifics here, but before I get into them, I’d like to hear what readers say. (I’m also late for a meeting.)

David Weinberger  and I posted New Clues on the Cluetrain site this morning. It’s the first new set of clues there in almost sixteen years. (The original went up in Spring of 1999.)

and I posted New Clues on the Cluetrain site this morning. It’s the first new set of clues there in almost sixteen years. (The original went up in Spring of 1999.)

The urgency behind New Clues is the retreat of businesses, networks and people into the kinds of silos and walled gardens that the Internet was built to transcend.

That transcendence will aways be there; but as more and more of what we do on the Net happens inside GAFTA (Goolge, Apple, Facebook, Twitter and Amazon) and other boxes, the less we create stuff in the wide open spaces, where it can work for anybody and everybody.

VRM is by nature distributed, not centralized. Like humanity. Like the Net. If VRM happens only inside silos, it will at best be a denatured subset of what it could and should have been. And that applies to much more than VRM.

The buzzing around NewClues and Cluetrain is high ebb right now. Here’s where to watch:

- Cluetrain mentions on Twitter

- NewClues mentions on Twitter

- New Clues discussion group on Facebook

- @Cluetrain on Twitter

I’m interested to see how well it persists. But whether it does or not may not matter all that much, because Cluetrain has already persisted for sixteen years, and will likely to continue to persist, enlarged by this new set of clues.

Some background.

When Cluetrain came out, the Web was a static place. Its main conceptual frame was real estate: sites at domains and locations that were built, browsed and visited, as if it were a library or a store. Time-to-index for search engines ranged from days to weeks. Now the Web is a live place. Real-time. Everything in it has the locational persistence of molecules in a fog. And in most cases the same life expectancy. (BTW, my son Allen brought up this distinction in a prophesy he uttered back in 2003.)

Some of the stuff we talked about back in the Static Web days is gone. (Online malls, anyone?) But Cluetrain did more than survive. It proved to have real value to a lot of people. (Just look at the posts at those links above.) If the tweeted molecules now buzzing around New Clues accrete to Cluetrain, they have a good chance of adding to the value that’s already there. And if they do, I’m sure that will be good for #VRM as well.

United

United  Doc Searls

Doc Searls