Agency is the power to act with effect in the world. We have agency when we type on a keyboard, hammer a nail, ride a horse or drive a car. Here’s a dictionary definition:

a·gen·cy (ā′jən-sē)

noun.

- The condition of being in action; operation.

- The means or mode of acting; instrumentality.

It is derived from agere: Latin for to do.

We are built to do a lot: with our brains, our opposable thumbs, our lack of fur, our capacity to sweat and to learn — and our strange ability to walk or run on two feet instead of four (almost ceaselessly, at least when we are young and fit) — we can do an amazing variety of things with our bodies.

For what we can’t do, we invent tools and machines. These extend our agency outward through technology. A hammer becomes another length of arm. With one in our hand, we have the power to drive nails with a metal fist. A car gives us an engine and wheels, so we can zoom down roads at dozens of miles (or kilometers) per hour. A plane gives us engines and wings, so we can fly far and high. Each expands our agency to distant horizons of effect and experience in the world.

Infrastructure and services expand what each and all of us can do as well. But at the base of human capacity is the individual’s ability to do stuff in the world. Or, in a word, agency.

Which brings me to the second world we built alongside the physical one we all share. That second world is the Internet: a Giant Zero shaped by an oddly simple protocol: TCP/IP. Never mind how it works. Just note what it does: reduce to zero the functional distance between everything and everybody on it. Also the cost.

As a way to expand human agency, the Internet has no rivals. It gives all our voices, all our ideas, all our actions, worldwide scale. Any of us can speak, write, publish and much more, across any distance, at levels of inconvenience and cost that veer toward zero.

And we’ve been doing that, routinely, ever since the Internet assumed its current form. (That happened in April 1995, when the NSFnet‘s backbone — one network within the Internet — was decommissioned and commercial activity, which the NSFnet forbade, could begin to flourish across the whole Net.)

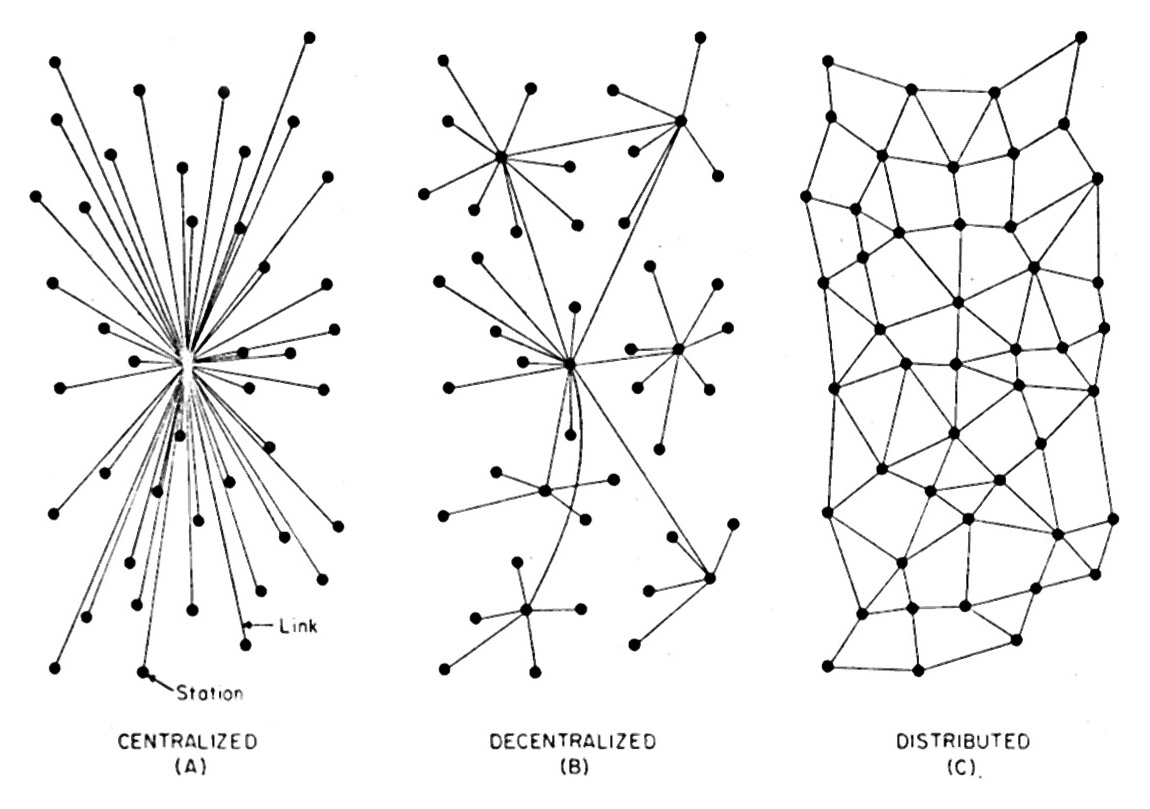

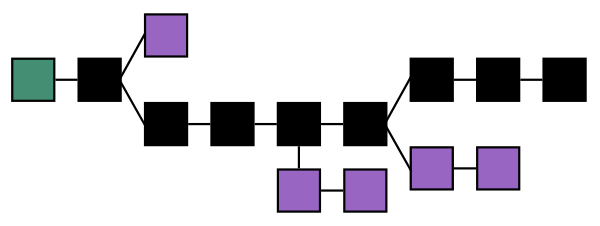

The Net has an end-to-end architecture. Every body and every thing is an end point, and the Net’s protocol does its best to move data between any and all of those. This is what Paul Baran, one of the Net’s fathers, described as a distributed design, rather than a centralized or decentralized one. Here is how he illustrated the difference, way back in 1962:

And that became the Net’s basic design. Or at least its ideal.

Yet, for the sake of convenience — especially in the early days of the Net, when most of us were still on dial-up — we defaulted to a client-server architecture for deploying servers and services. With client-server, each server is a central point, which makes the Net, in a practical sense, a decentralized thing, rather than a distributed one.

And yet the distributed nature of the Net persists, grounding our agency in the world it defines.

Conflicts between centralized, decentralized and distributed capacities on the Net — and uneven development of tools and services enlarging our agency — are behind many of our crises on the Net today.

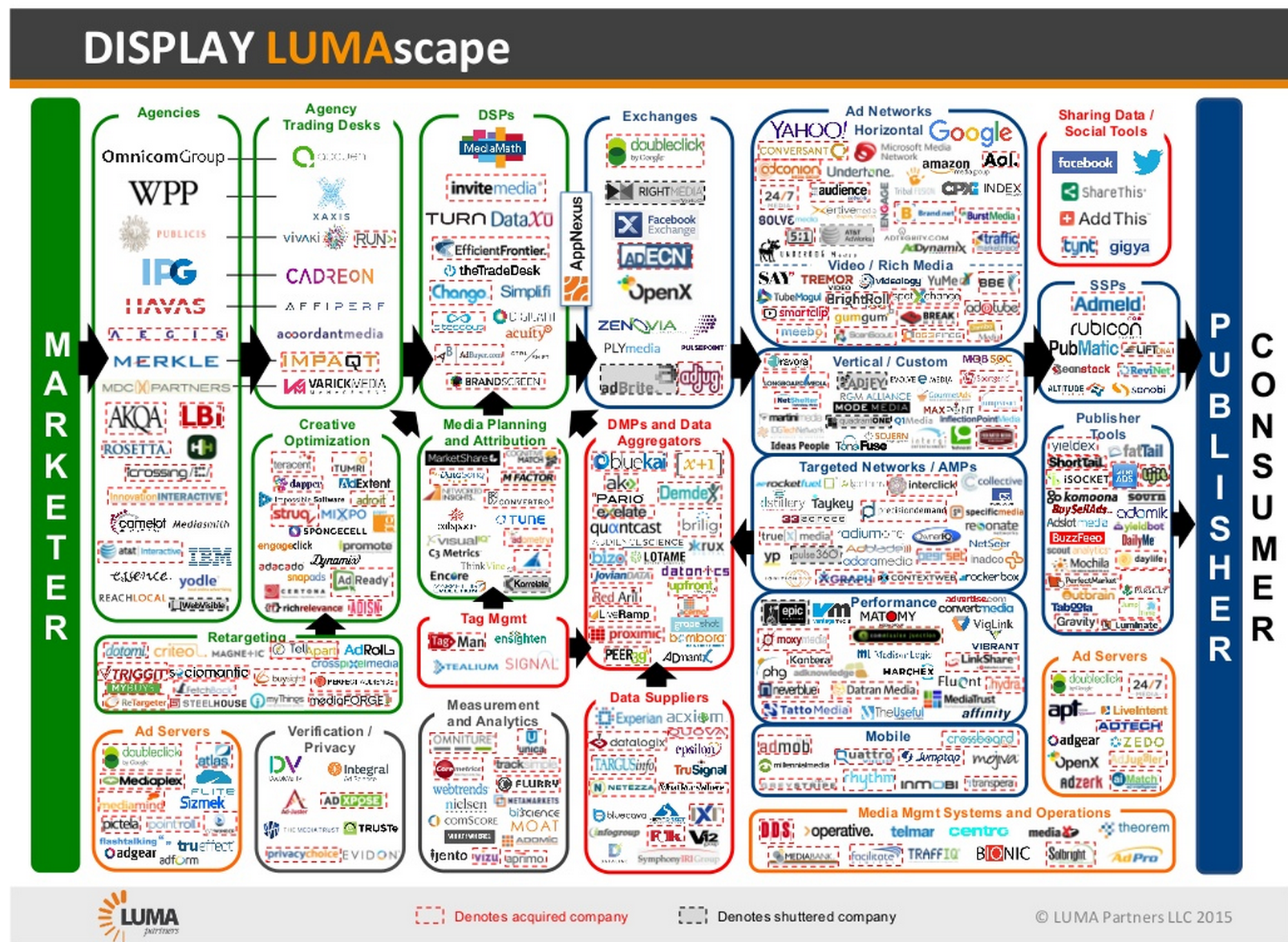

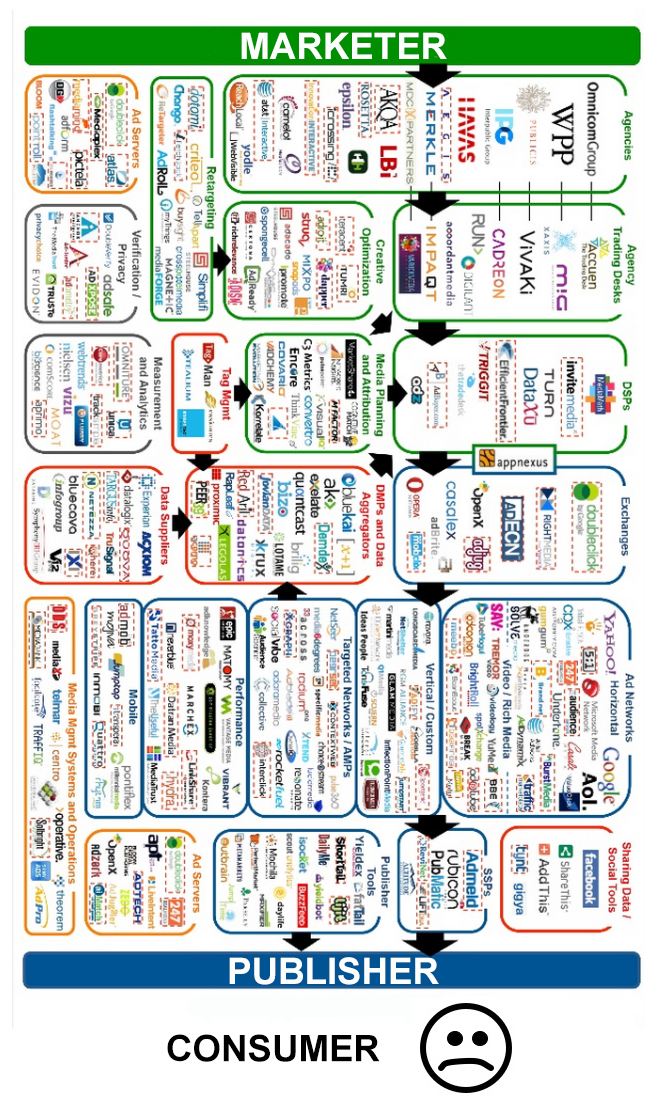

Take privacy for example. It’s a huge issue. Survey after survey (e.g. from Pew, TRUSTe and Customer Commons) say that 90% and more of us are concerned about personal privacy on the Net, don’t trust many service providers, or lie and hide to obscure personal identity. Advertising and tracking blockers are the most popular browser extensions, and with good reason: we are still naked on the Net.

That’s because the Net, like nature in the physical world, doesn’t come with privacy installed. We have to make it for ourselves. In the physical world we did it by inventing clothing and shelter. In the virtual world we still don’t have either. Tracking blockers are fig leaves at best. They also all work differently. We are still in early times.

Since we have no privacy yet (other than by staying off the Net, or by isolating ourselves on it by declining to accept cookies and staying away from services such as Google’s and Facebook’s), we tend to think about privacy in terms of secrets: things we don’t want others to know about us. But think instead about what we do to create privacy in the physical world, with clothing and shelter. Both do more than cover our bodies and and our lives. We express both. We also express with them. Our clothing and shelter send signals about ourselves. They speak of our tastes, our gender, our status, our memberships. Most of these speakings are subtle, but many are not. What matters is that they all valve our exposure to others. Buttons and zippers on our clothes speak of what can, can’t and shouldn’t be opened by others, without permission. Doors, shades and shutters on our homes do the same.

All of those things facilitate our agency. We need the same in the networked world.

The main difference is that we’ve had thousands of years to work them out in the physical world, and just twenty in the networked one. In the history of civilization, and even of business, this is close to nothing. We’re barely started.

There will, inevitably, emerge a symbiosis between centralized, decentralized and distributed capacities. Brian Behlendorf uses the term “minimum viable centralization” to label what we’re looking for here. Meanwhile we have maximum viable centralization on a network that is also distributed by design. Just like the humans on it.

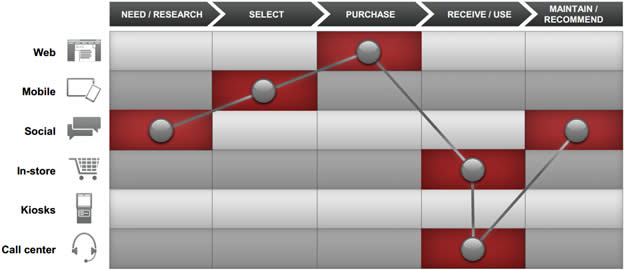

We are seeing today a collapse of intermediary institutions. Publishing (e.g. blogs) Hospitality (e.g. Airbnb), dispatch (e.g. Uber), broadcast (e.g. Meerkat and Periscope) and payments (e.g. Bitcoin) come quickly to mind, and many more are coming along. Yet through all of those there must remain some degree of trust in the graces that institutions — governments and companies — alone can provide. How can their minimum viable agencies help us enlarge our own? That’s the main challenge for the coming years.

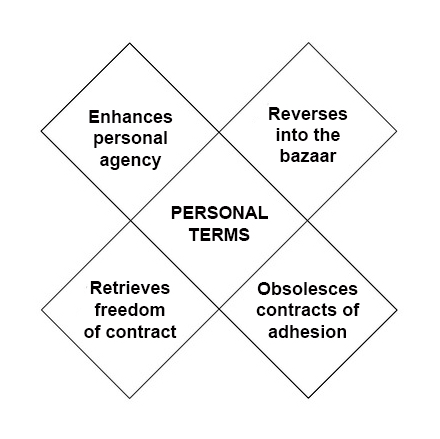

The question we need to ask, as we address that challenge through VRM, is this: What is best done by the individual, and what is best done by the institution — and how an the two work together?

To answer that, agency must be key. Without it we’ll only get more centralized BS to distrust.

I’m serious.

I’m serious.