Look up privacy trade-offs on Google and you’ll get more than 150,000,000 results. The assumption in many of those is that privacy is something one can (and often should) trade away. Also that privacy trading is mostly done with marketers and advertisers, the most energetic of which take advantage of social media such as Twitter, FourSquare and Blippy.

I don’t think this has to be so.

One example of a trade-off story is this one on public radio’s Marketplace program, which I heard this evening. It begins with the case of Shea Sylvia, a FourSquare user who got creeped out by an unwelcome call from a follower who knew her location. Marketplace’s Sally Herships says,

There are millions of Sylvias out there, giving away their private information for social reasons. More and more, they’re also trading it in for financial benefits, like coupons and discounts. Social shopping websites like Blippy and Swipely let shoppers post about what they buy. But first they turn over the logins to their e-mail accounts or their credit card numbers, so their purchases can be tracked online.

Later, there’s this (the voice is Herships again):

Alessandro Acquisti researches the economics of privacy at Carnegie Mellon, and he says the value we put on privacy can easily shift. In other words, if giving away your credit card information or even your location in return for a discount or a deal seems normal, it must be OK.

ALESSANDRO ACQUISTI: Five years ago, if someone told you that there’d be lots of people going online to show, to share with strangers their credit card purchases, you probably would have been surprised, you probably would thought, “No, I can’t believe this. I wouldn’t have believed this.”

But Acquisti says, when new technologies are presented as the norm, people accept them that way. Like social shopping websites.

HERSHIPS: So the more we use sites like Blippy, the more we’ll use sites like Blippy?

ACQUISTI: Or Blippy 2.0.

Which Acquisti says will probably be even more invasive, because as time passes, we’re going to care less and less about privacy.

Back in Kansas City Shea Sylvia is feeling both better and worse. She thinks the phone call she got that night at the restaurant was probably a prank. But it was a wake up call.

What we’re dealing with here is an evanescent norm. A fashion. A craze. I’ve indulged in it myself with FourSquare, and at one point was the “mayor” of ten different places, including the #77 bus on Mass Ave in Cambridge. (In fact, I created that location.) Gradually I came to believe that it wasn’t worth the hassle of “checking in” all over the place, and was worth nothing to know Sally was at the airport, or Bill was teaching a class, or Mary was bored waiting in some check-out line, much as I might like all those people. The only time FourSquare came in handy was when a friend intercepted me on my way out of a stop in downtown Boston, and even then it felt strange.

The idea, I am sure, is that FourSquare comes to serve as a huge central clearing house for contacts between companies selling stuff and potential buyers (that’s you and me) wandering about the world. But is knowing that a near-infinite number of sellers can zero in on you at any time a Good Thing? And is the assumption that we’re out there buying stuff all the time not so wrong as to be insane?

Remember that we’re the product being sold to advertisers. The fact that our friends may be helping us out might be cool, but is that the ideal way to route our demand to supply? Or is it just one that’s fun at the moment but in the long term will produce a few hits but a lot of misses—some of which might be very personal, as was the case with Shea Silvia? (Of course I might be wrong about both assumptions. What I’m right about is that FourSquare’s business model will be based on what they get from sellers, not from you or me.)

The issue here isn’t how much our privacy is worth to the advertising mills of the world, or to intermediaries like FourSquare. It’s how we maintain and control our privacy, which is essentially priceless—even if millions of us give it away for trinkets or less. Privacy is deeply tied with who we are as human beings in the world. To be fully human is to be in control of one’s self, including the spaces we occupy.

An excellent summary of our current privacy challenge is this report by Joy L. Pitts (developed as part of health sciences policy development process at the Institute of Medicine, the health arm of the National Academy of Sciences). It sets context with these two quotes:

“The makers of the Constitution conferred the most comprehensive of rights and the right most valued by all civilized men—the right to be let alone.”

—Justice Louis Brandeis (1928)

“You already have zero privacy anyway. Get over it.”

—Scott McNealy, Chairman and CEO of Sun Microsystems (1999)

And, in the midst of a long, thoughtful and well-developed case, it says this (I’ve dropped the footnotes, which are many):

Privacy has deep historical roots. References to a private domain, the private or domestic sphere of family, as distinct from the public sphere, have existed since the days of ancient Greece. Indeed, the English words “private” and “privacy” are derived from the Latin privatus, meaning “restricted to the use of a particular person; peculiar to oneself, one who holds no public office.” Systematic evaluations of the concept of privacy, however, are often said to have begun with the 1890 Samuel Warren and Louis Brandeis article, “The Right of Privacy,” in which the authors examined the law’s effectiveness in protecting privacy against the invasiveness of new technology and business practices (photography, other mechanical devices and newspaper enterprises). The authors, perhaps presciently, expressed concern that modern innovations had “invaded the sacred precincts of private and domestic life; and . . . threatened to make good the prediction that ‘what is whispered in the closet shall be proclaimed from the house-tops.’” They equated the right of privacy with “the right to be let alone” from these outside intrusions.

Since then, the scholarly literature prescribing ideal definitions of privacy has been “extensive and inconclusive.” While many different models of privacy have been developed, they generally incorporate concepts of:

- Solitude (being alone)

- Seclusion (having limited contact with others)

- Anonymity (being in a group or in public, but not having one’s name or identity known to others; not being the subject of others’ attention)

- Secrecy or reserve (information being withheld or inaccessible to others)

In essence, privacy has to do with having or being in one’s own space.

Some describe privacy as a state or sphere where others do not have access to a person, their information, or their identity. Others focus on the ability of an individual to control who may have access to or intrude on that sphere. Alan Westin, for example, considered by some to be the “father” of contemporary privacy thought, defines privacy as “the claim of individuals, groups or institutions to determine for themselves when, how and to what extent information about them is communicated to others.” Privacy can also be seen as encompassing an individual’s right to control the quality of information they share with others.

In the context of personal information, concepts of privacy are closely intertwined with those of confidentiality and security. Privacy addresses “the question of what personal information should be collected or stored at all for a given function.” In contrast, confidentiality addresses the issue of how personal data that has been collected for one approved purpose may be held and used by the organization that collected it, what other secondary or further uses may be made of it, and when the permission of the individual is required for such uses.Unauthorized or inadvertent disclosures of data are breaches of confidentiality. Informational security is the administrative and technological infrastructure that limits unauthorized access to information. When someone hacks into a computer system, there is a breach of security (and also potentially, a breach of confidentiality). In common parlance, the term privacy is often used to encompass all three of these concepts.

Take any one of these meanings, or understandings, and be assured that it is ignored or violated in practice by large parts of today’s online advertising business—for one simple reason (I got from Paul Trevithick long ago): Individuals have no independent status on the Web. Instead we have dependent status. Our relationships (and we have many) are all defined by the entities with which we choose to relate via the Web. All those dependencies are silo’d in the systems of sellers, schools, churches, government agencies, social media, associations, whatever. You name it. You have to deal with all of them separately, on their terms, and in their spaces. Those spaces are not your spaces. (Even if they’re in a place called MySpace. Isn’t it weird to have somebody else using the first person possessive pronoun for you? It will be interesting to see how retro that will seem after it goes out of fashion.)

What I’m saying here is that, on the Web, we do all our privacy-trading in contexts that are not out in the open marketplace, much less in our own private spaces (by any of the above definitions). They’re all in closed private spaces owned by the other party—where none of the rules, none of the terms of engagement, are yours. In other words, these places can’t be private, in the sense that you control them. You don’t. And in nearly all cases (at least here in the U.S.), your “agreements” with these silos are contracts of adhesion that you can’t break or change, but the other party can—and often does.

These contexts have been so normative, for so long, that we can hardly imagine anything else, even though we have that “else” out here in the physical world. We live and sleep and travel and get along in the physical world with a well-developed understanding of what’s mine, what’s yours, what’s ours, and what’s none of those. That’s because we have an equally well-developed understanding of bounded spaces. These differ by culture. In her wonderful book French or Foe, Polly Platt writes about how French proxemics—comfortable distances from others—are smaller than those of Americans. The French feel more comfortable getting close, and bump into each other more in streets, while Americans tend to want more personal space, and spread out far more when they sit. Whether she’s right about that or not, we actually have personal spaces on Earth. We don’t on the Web, and in Web’d spaces provided by others. (The Net includes more than the Web, but let’s not get into that here. The Web is big enough.)

So one reason that privacy trading is so normative is that dependency requires it. We have to trade it, if that’s what the sites we use want, regardless of how they use whatever we trade away.

The only way we can get past this problem (and it is a very real one) is to create personal spaces on the Web. Ones that we own and control. Ones where we set the terms of engagement. Ones where we decide what’s private and what’s not.

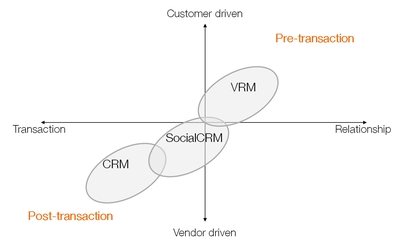

In the VRM development community we have a number of different projects and companies working on exactly this challenge. The Mine Project is pure open source and has a self-explanatory name. Others (Azigo, Kynetx, MyDex, Switchbook and others) are open in many ways as well, and are working together to create (or put to use) common code, standards, protocols, terminologies and other conventions on which all of us can build privacy-supporting solutions. You’ll find links to some of the people involved in those efforts (among others) in Personal Data Stores, Exchanges, and Applications, a new post by Joe Andrieu (of Switchbook). There’s also the One example is the Personal Information Sharing workgroup and UMA (User Managed Access) at Kantara. (For more context on that, check out Iain Henderson’s unpacking of the Personal Data Ecosystem.) There’s also our own work at ProjectVRM and the Berkman Center, which has lately centered on developing Creative Commons-like legal tools for both individuals and companies. What matters most here is that a bunch of good developers are working on creating spaces online that are as natural, human, personal—and under personal control—as the ones we enjoy offline.

Once we have those, the need for privacy trade-offs won’t end. But they will begin to make the same kind of down-to-Earth sense they do in the physical world. And that will be a huge leap forward.

Here’s a great video

Here’s a great video