Prologue

ø

Welcome to my Exploring Islam blog! This site is an aesthetically and analytically inspired reaction to the course I took: AI 54 – For the Love of God and His Prophet: Religion, Literature, and the Arts in Muslim Cultures. As a class, we approached the study of Islam with a strong emphasis on a contextual approach of examining Islam and Muslim cultures. Going beyond just a devotional viewpoint of studying the fundamental religious beliefs and practices that a devotional standpoint would focus on, the contextual approach considers Islam as a religion that developed and continues to evolve within a dynamic environment. The contexts span historical, geopolitical, socioeconomic, literary and artistic dimensions and more.

As I will uncover in my blog posts, I analyzed themes and patterns I saw emerging in the course material, relating and synthesizing what I saw and reconciling it with creative pieces of my creation. To channel reactions and discoveries, my constructed pieces spanned various mediums from hand-drawn illustrations and models, to digital visualizations, and even curated music playlists. I generally make the assumption that my viewer is a Westerner who desires to learn more about Islam beyond what they have seen and heard represented by the modern Western mainstream media. Fittingly, my ultimate objective with my pieces is to leave the viewer with an increased appreciation for the diverse contexts Islam can, and should be considered in. My collection achieves this objective by clarifying the common Western mis-equation of all things Muslim with the Middle East, instead highlighting Islam’s geopolitical and historical cosmopolitan underpinnings, and the overlooked pluralist theology roots of Islam.

The Stereotype Problem

Today in the US and other parts of the West, the media is filled with news stories and accounts of what’s labeled as fundamentalist Islam waging war against the West. Due to the availability heuristic after being exposed to such stories filling the news media, and the current geopolitical environment surrounding, Muslims and the Middle East have been essentially equated together in the West’s public conscience. Any mass-media consuming Westerner is bound to receive bombardment from media about anti-Islam interest groups. So it has become harder for Westerners to overcome initial stereotypical images of Islam and Muslims and see the intricacies of Islamic culture and the many contexts that Islam exists in globally.

In our final week of lecture we learned of the many interest groups that lobby US lawmakers relentlessly, hoping to prohibit Muslims from entering the United States. However, they claim this is necessary for keeping the US safe from a relatively small militant subset of Muslims set on waging jihad against the West. This simplified viewpoint of the other by Islamophobes casting all Muslims as Middle East born radical Sunni militants with close ties to oil money ends up leaving many Muslims effectively silenced. As a result, the other contexts of Islam do not receive the same amount of attention as the violent form receiving the bulk of modern geopolitical attention.

Muslim Diversity

There is a large amount of Muslim diversity today, and my selection of pieces deals with the theme of Islam as historically integrating itself into local cultures as a cosmopolitan phenomenon. I start by looking at the style of Islamic architectures across the world mapped out to show pattern as well as variation in spread around the Muslim world and beyond. I invite the viewer to look with their own eyes, to visually pick out architecture commonalities they see between the disparate mosques around the world: minarets, domes, tiling, archways, to name a few components distinct to local styles. I even look at Islam’s diversity from an anthropological approach, illustrating the multinational and multiethnic diversity embedded in Islamic Hip Hop. These pieces engage in a conversation about the breadth of Islam’s diversity. However, by also placing them side by side with pieces such as my model of Husain’s cloak, I also raise questions encouraging a deep understanding of different Islamic traditions.

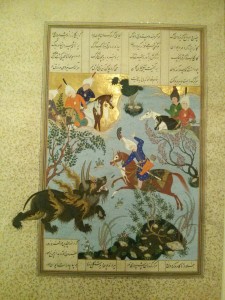

How did diverse sets of traditions develop in the rich cultural contexts around them? In my case, Husain’s cloak, by being a prop illustration of Husain’s Martyrdom popular in Taziyeh tradition, demonstrates cultural diffusion of Muslim texts meeting Persian dramatic form. Meanwhile, my playlist for the Miraj in itself is a musical depiction of a variant of the Miraj story already embedded with local Swahili embellishments, which was then on top of that translated to English! These pieces support Islam’s history of embedding itself in many local traditions. Circling back, my blog on the cosmopolitan Islam in hip hop also touches upon one historical storyline that brought Islam to modern-day Ethiopia – from the movement of some of Muhammad’s first followers. My post on Mongol influence on Persian art also makes a similar point – the conquests of Tamberlane which coincided with the Timurid period, and coinciding with a possibly new dynamic style of Persian art once the Timurid rulers adopted the aesthetics of the Persians. Thus, the synergy of Islam and local traditions would not be possible without Islam’s history of persecution and conquest which influenced the migration patterns of Muslims who brought Islam with them where they went; however persecution and conquest are far from the only agents for Islam’s dissemination, merely the ones that my pieces can attest to.

While there is Islamic unity with the Qu’ran text and Allah, being a Muslim still spans a large swath of theological diversity. This diversity ranges from ideological divides based on how to decide Mohammad’s succession that created a Sunni and Shi’ite split. Not to mention the wide variety of integration of Sufi mysticism in the daily lives of Muslims across the globe. My piece on Husain’s cloak doubles as another conversation point for launching into the theological diversity discussion. Husain’s cloak not only touches upon the Shi’ite difference in succession ideology, but raises second level nuances: variance between the Sunni and Shi’ite Shahada with a clause about Ali, and the lineage of Shia Imams.

“The Silent Islam”

As interlocutors of this course, we explored what Professor Asani referred to as “The Silent Islam” – less-geopolitical, mixed and diverse faces of Islam that are less represented in the forefront of public attention today. These faces of the “Silent Islam” are there for us to see though if we look carefully enough! As our class trip to the Metropolitan Art Museum of New York City proved to take us through over a thousand years of Islamic art from different parts of the Islamic empires, we see that Silent Islam is about influence over a variety of factors both fast and slow changing. Aspects of Silent Islam reach quietly far beyond the oil regimes of the modern Middle East and the fundamentalist sects of Sunni Islam that modern day geopolitics is focused on today. Ultimately what drives Silent Islam is its pluralist roots which extend from the theological aspects of Muslim life to even the aesthetic.

One important aspect of Islam less considered by outsiders, is the intimate tie to other Abrahamic religions. Judaism and Christianity have much more in common with Islam than many Westerners may think. In our course curriculum, we touched upon shared beliefs such as the important role of prophets across the three religions; of course Muslims recognize the role of Muhammad as the last Prophet. However, much of Islam recognizes biblical figures such as Moses, Joseph and more. They are even held to high importance, serving as Muhammad’s interlocutors during his Miraj as explained in my playlist blog post. In my museum observations, I also included a piece from the Timurid period which serves as an example of how Adam and his role as the first human and first prophet was important in illustrated Islamic texts even 700 years after Islam’s founding in the middle of Iran when Mongols were ruling.

Meanwhile, our course also stressed the pluralist roots of the term “muslim”. Meaning believer, “muslim” was originally a term that meant anyone who took the Shahada, at one point arguably including not just followers of Muhammad, but followers of Allah/God. However in the dynamic changing context of Islam’s early days, there came a need to identify and delineate the separation between Islam and other Abrahamic religions, which spurred the adoption of the term “Muslim” to refer to practitioners of Islam who took the Shahada’s second clause as well – believing in Muhammad as the last prophet, and classifier non “Muslims” as infidels. However even then, most Muslims do not call for militant jihad against infidels. My Ghazal word cloud illustrates the centrality of God, and shows that for example, in the Urdu poems of poets like Iqbal, there are no signs of militant representations of jihad as focused on by the media. Instead Islam is structured around God, love and acceptance. This shows through in the core of the heart word cloud, but yet is unseen in our modern world today at the macroscopic level; there is a compassionate and passionate side of Islam as well, not just the popularized one that the Western world only knows for its strict sharia.

Send off into the Blog

It is my hope as the author that you as the viewer will come away with a greater understanding of the diversity within the Islamic world, and within Islam itself. Furthermore, I hope you can see beyond how Islam is covered by Western media today to experience the silent sides of Islam that are not as well represented and invisible to many in the West. With that, I invite you to explore these themes further, as I send you off to peruse my collection of aesthetic responses to this course.