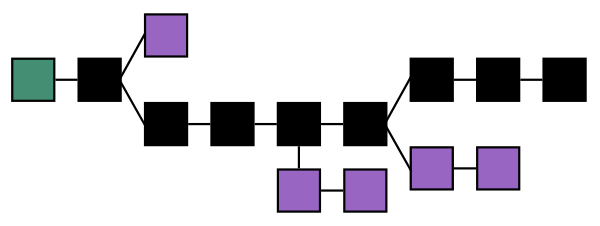

We’ve been waiting a long time for a protocol to connect VRM (customers’ Vendor Relationship Management) with CRM (vendors’ Customer Relationship Management).

Now we have one. It’s called JLINC, and it’s from JLINC Labs. It’s also open source. You’ll find it at Github, here. It’s still early, at v.0.3. So there’s lots of opportunity for developers and constructive hackers of all kinds to get involved.

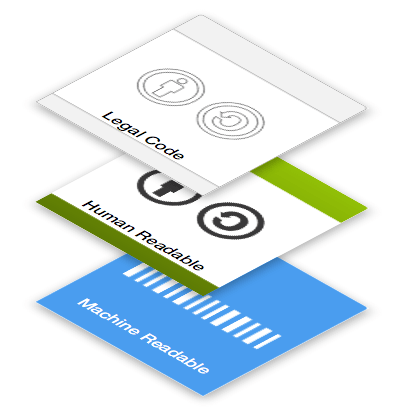

Specifically, JLINC is a protocol for sharing data protected by the terms under which it is shared, such as those under development by Customer Commons and the Consent and Information Sharing Working Group (CISWG) at Kantara.

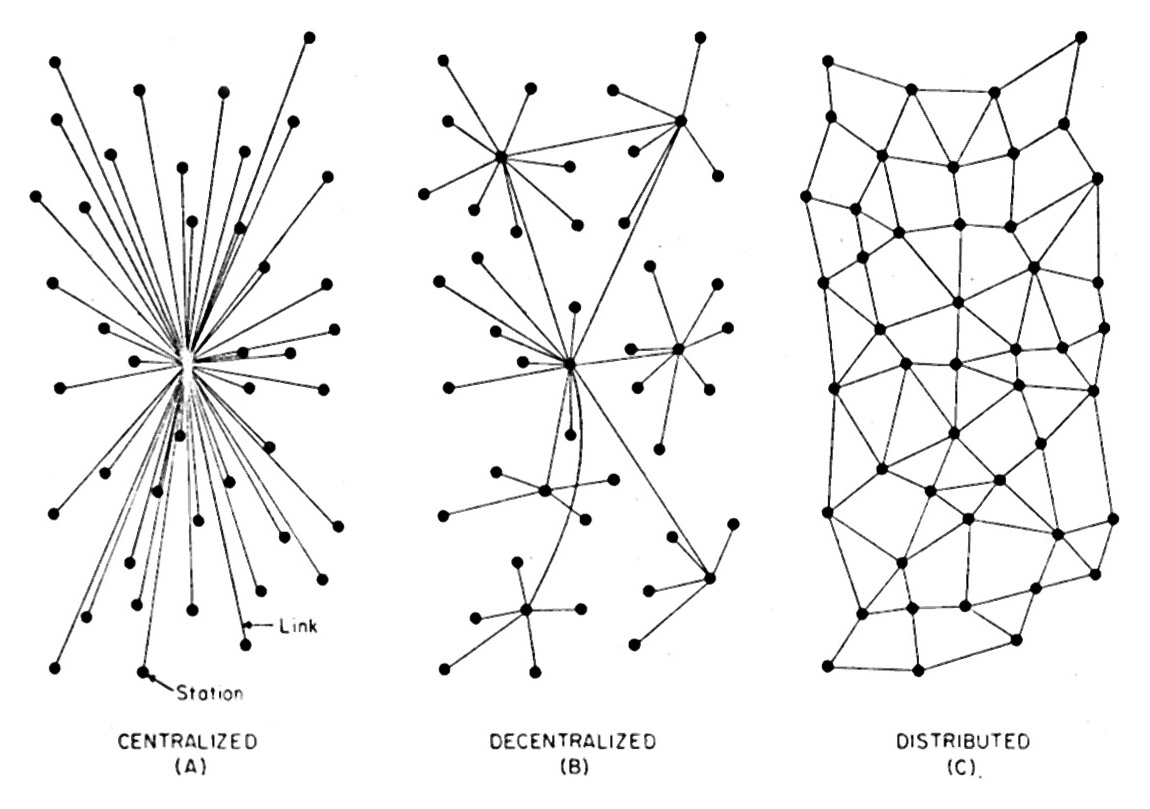

The sharing instance is permanently recorded in a distributed ledger (such as a blockchain) so that both sharer and recipient have a permanent record of what was agreed to. Additionally, both parties can build up an aggregated view of their information sharing over time, so they (or their systems) can learn from and optimize it.

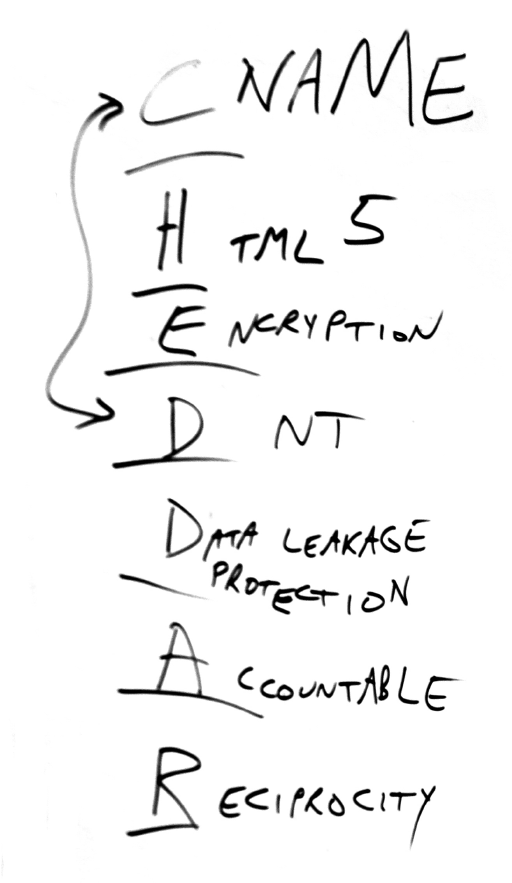

The central concept in JLINC is an Information Sharing Agreement (ISA). This allows for—

- the schema related to the data being shared so that the data can be understood by the recipient without prior agreement

- the terms associated with the data being shared so that they can be understood by the recipient without prior negotiation

- the sharing instance, and any subsequent onward sharing under the same terms, to be permanently recorded on a distributed ledger of subsequent use (compliance and analytics)

To test and demonstrate how this works, JLINC built a demonstrator to bring these three scenarios to life. The first one tackled is Intentcasting , a long-awaited promise of VRM. With an Intencast, the customer advertises her intention to buy something, essentially becoming a qualified lead. (Here are all the ProjectVRM blog posts here with the Intentcasting tag.)

Obviously, the customer can’t blab her buying intention out to the whole world, or marketers would swarm her like flies, suck up her exposed data, spam her with offers, and sell or give away her data to countless other parties.

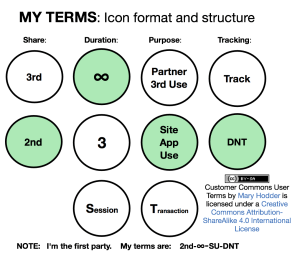

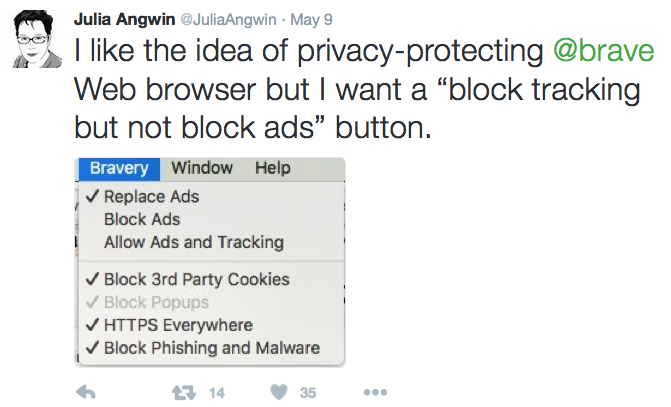

With JLINC, intention data is made available only when the customer’s terms are signed. Those terms specify permitted uses. Here is one such set (written for site visiting, rather than intentcasting):

These say the person’s (first party’s) data is being shared exclusively with the second party (the site), for no limit in time, for the site’s use only, provided the site also obey the customer’s Do Not Track signal. I’m showing it because it lays out one way terms can work in a familiar setting

For JLINC’s intentcasting demonstration, terms were limited to second party use only, and a duration of thirty days. But here’s the important part: the intentcast spoke to a Salesforce CRM system, which was able to—

- accept or reject the terms, and

- respond to the intentcast with an offer,

- while the handshake between the two was recorded in a blockchain both parties could access

This means that JLINC is not only a working protocol, but that there are ways for VRM tools and systems to use JLINC to engage CRM systems. It also means there are countless new development opportunities on both sides, working together or separately.

Here’s another cool thing: the two biggest CRM companies, Salesforce and Oracle, will hold their big annual gatherings in the next few weeks. This means JLINC and VRM+CRM can be the subjects of both conversation and hacking at either or both events. Specifically, here are the dates:

- Oracle’s OpenWorld 2016 will be September 18-22.

- Salesforce’s Dreamforce 2016 will be October 4-7.

Both will be at the Moscone Center in San Francisco.

Conveniently, the next VRM Day and IIW will both also happen, as usual, at the end of October:

Both will take place at the Computer History Museum, in downtown Silicon Valley. And JLINC, which was launched at the last VRM Day, is sure to be a main topic of discussion, starting at VRM Day and continuing through IIW, which I consider the most leveraged conference in the world, especially for the price.

If all goes well, we’ll have some examples of VRM+(Oracle and/or Salesforce) CRM to show off at Demo Day at IIW.

Love to see other CRM vendors show up too. You listening, SugarCRM? (I spoke about VRM+CRM at SugarCon in 2011. Here’s my deck from that talk. What we lacked then, and since, was a protocol for that “+”. Now we have it. )

Big HT to Iain Henderson of both JLINC Labs and Customer Commons, for guiding this post, as well as conducting the test that showed, hey, it can be done!

Save

I’m serious.

I’m serious.